This paper interrogates transability — the need or desire to transition from supposed binary states of physical ability to physical disability - by positioning it within the boundaries of acceptable body modification. The pathology of this bodily transition, noted in the literature, is dissected to inquire how compulsory able-bodiedness and ableism enable the pathologization of transabled people. Transabled people depart from ableist compulsions "to never want to be disabled" but needing it to feel "whole" or who they really are. A key informant interview with a transabled man, who has lived as a paraplegic for a decade, provides a humanizing account of this often problematic identity from the standpoint of the disability community. Instead of concluding with resolution about the meaning of transability or disability as body art — the piece closes with several questions to promote a dialog on the boundaries of transition.

"One must be a work of art, or wear a work of art."

Sean O'Connor1 gradually transitioned from an ambulatory life to wheelchair use but his fascination with disability began at a young age. O'Connor began to recognize feelings of wanting to be paralyzed around age three when a friend of his father's taught him to make a brace for a sprained foot. With time, he grew to understand that he longed to be paralyzed and began renting wheelchairs at age ten, secretly using them in the basement of his home. At age twenty he bought a wheelchair, which he used frequently in his home and publicly in cities distant from his own. In his thirties, he made a complete transition to full-time wheelchair use when he moved to a new city to live with his then wife, a paraplegic. About his transition he said:

While I had extensive experience using a wheelchair, things just can't compare from part-time to full-time use. Being known as a paraplegic somewhat takes away your ability to choose whether you use the chair or not. In effect, you don't have a choice but to wheel. This lack of choice was very good for me. It was part of my need. I need to need to use a wheelchair. I need to not have a choice in the matter. And being known as a para did just that for me. It filled that need in a way (O'Connor, 2007).

He states that it is "pretty much a dream of most people who are transabled, to live full-time as who/what they feel they are. And if we can't be it, we want to get as close to it as possible" (personal communication, 2008).

O'Connor's late wife helped facilitate his transition to full-time wheelchair use: she accepted all aspects of him and introduced him to her friends in the disability community. Focused on learning about disability through a scholastic-activist lens, his view of disability became three-dimensional: "I finally was home. Home within myself" (personal communication, 2008). O'Connor found not only home within himself but also in the disability community. He has been a dedicated disability rights activist for over eight years and at one point served in a management role in one of the largest Centers for Independent Living in the United States. The dedication and passion that O'Connor has for promoting equality for disabled people—demonstrated by his work in one of the main pillars of the disability community—challenges a common belief about transabled people: that they desire acquisition of disability to procure some of the negative aspects of the social identity of disability, namely pity and coddling attention, without recognition of the positive side of disability culture and politics.

Ethical Issues in Transitioning to a Disabled Person

Despite O'Connor's active role in the disability rights movement, the disability community has been hostile to embracing transabled individuals. My conversations with several of my comrades in the disability community have revealed that their reasoning hinges on the notion of authenticity. Transabled people get to choose, on some level, if and when they want to deal with disability. O'Connor's life reflects this choice between performing the role of a wheelchair user and an ambulatory one by the fact that he spends 98% of his time at home walking around (personal communication, 2008). He claims to do so because his current partner does not accept his transability and he lacks the financial ability to have a fully accessible home. Sean contends being forced to walk entails a great deal of cognitive dissonance and distress, which I empathized with as I interviewed him. However, upon further inquiry, Sean admitted he knows that it is much harder to cook and do laundry sitting in a wheelchair. That admission, even with the pain he expresses about it, makes the performance of disability all the more problematic for those of us who might love to preserve energy by choosing when to perform able-bodiedness (personal communication, 2008). Interestingly, he does not mention this potentially important detail in his personal narrative featured in the anthology Body Integrity Identity Disorder: Psychological, Neurobiological, Ethical and Legal Aspects (2009). O'Connor explained via e-mail that he did not include this detail because of "no reason in particular" (personal communication, 2009).

In transitioning to a disabled body, a transabled individual may use resources available to individuals impaired at birth or through some unintentional illness or accident. These resources include, but are not limited to, the use of accessible bathroom stalls and parking spaces as well as the receipt of limited governmental benefits. Further, transabled people in the preliminary state of transition can decide whether they want to take on expenditures needed for physical access such as hand-controls, catheters, and ramps. Despite the challenging nature of unpacking the meanings of transability from the perspective of a disabled person, I deliberately sought to push myself to understand it by positing it within the spectrum of other forms of body modification or body art. In doing so I explore how transability can be viewed as a catalyst to include disability within the category of body art.

Background of Transability

Transabled people are individuals who need to acquire a physical impairment despite having been born or living in physically unimpaired bodies. Although much of the literature about the topic frames transability as a mental illness causing people to choose the acquisition of disability (Money et al 1977; Bruno, 1997), many transabled individuals make it clear that there is no choice involved (personal communication, 2008). I deliberately use the term 'transability' rather than its medicalized label, Body Identity Integrity Disorder (BIID), because the intent of this paper is to question why this identity is pathologized. O'Connor coined the term 'transability' in 2004 to make an apparent lingual comparison to the word 'transgender' as both words signify people transitioning from one state of embodiment to another (personal communication, 2008). He stated that BIID is not often embraced by those who identify as transabled, just as few transgender people claim or use the medical label Gender Identity Disorder (GID). Part of the issue with both of these medical labels is that they construct transgender and transabled identities as mental illnesses (personal communication, 2008).

Transability activists analogize their identities to transgender identities for several reasons. Both groups seek surgical modification of their bodies to reconcile external embodiment with internal identity (Elliot, 2000; First, 2005; Lawrence, 2006). Dr. Michael First, who coined the label Body Integrity Identity Disorder, found in his study of 52 people who desired elective amputation that the majority expressed similar desires as many transgender people. First found that the onset of discovering the desire to acquire disability occurred during early childhood, much like many transgender people (First, 2005). Additionally, transgender and transabled people often relate parallel narratives of being "trapped in the wrong body" (Lawrence, 2006). Their desire for body modification is motivated by the need to feel "whole" and to have their appearance reflect their internal identity (personal communication, 2008). These narratives conflict with the imposed stereotype of a sexual predilection; divorcing sexuality from the issue, transabled people need to acquire impairment in order to visually produce signifiers of their true identity (First, 2005). Transabled people, like transgender people, often experience depression because their bodies do not match their psyches (First, 2005). Many claim the only way to effectively cure their depression is to change their bodies to reflect their identity, not through pharmacological or psychological intervention (personal communication, 2008). While there is no monolithic narrative for every transabled or transgender person, the similarities in some of their stories is striking.

Even if a transabled person is able to afford medical intervention, transabled people are, in most cases, denied the surgeries needed to reconcile their bodies and their identities. The Hippocratic Oath, by which medical practitioners pledge to "do no harm" to their patients, is the main barrier between a transabled person and their disability; practitioners cannot aid individuals in acquiring an impairment that is presumed to have a detrimental effect on their life (Johnston and Elliot, 2002). This barrier depends on viewing disability as a form of embodiment that has only negative effects in one's life — thus, reifying medicalization of disability. The Hippocratic Oath entails an uneven application in practice. Medical interventions that many view as barbaric and harmful, such as plastic surgery, are deemed both legal and ethical because surgeons work to transform the bodies of their patients into the ideal standard of beauty, health and embodiment (Jordan, 2004).

Despite my desire to problematize the application of the Hippocratic Oath, I admittedly was initially hesitant to support transability. I challenged myself to try to understand O'Connor's need to be disabled because of my exposure to transgender theory, politics and people in San Francisco. In fact, an intense debate with my transgender cohort (in a sexuality studies graduate program devoted to exploring the sociopolitical issues around sexuality) led me to the topic of transability. One evening, we discussed whether people who were perceived to be Euro-American could reasonably wear their hair in dreadlocks. My colleague claimed that Euro-American people could not fully internalize and understand the historical meaning of dreadlocks and thus should not appropriate them based on fashion. I claimed many people modify their hair through dying, perming and other methods — without attempting to pass as another race. After the taxing debate with my classmate, I decided I needed to try to personalize the issue of appropriating cultural signifiers, particularly analyzing the reasonability of the need to appropriate central aspect of my own identity: disability. Asking the question whether it is acceptable to acquire a disability has been truly difficult to think about because it has forced me, a disabled woman, to inquire why someone would want an identity and body that often causes both social and physical pain. Even with the years I have spent with this topic, I have not resolved this tension in myself nor does this piece offer a resolved analysis of transability.

The Spectrum of Body Art

Trends have constructed which forms of bodily agency — body movement, adornment and modification — are acceptable in a given geographic and temporal locality (Gilman, 2002). Certain forms of body modification practices, such as tattooing and piercing, have seen a surge in acceptability in recent years. For example, it is estimated that those with tattoos number anywhere between 7 million and 20 million people in the United States alone and these numbers continue to rise (Stirn, 2003). Most individuals modify their bodies through piercing, tattooing and other practices without facing the stigma of criminalization and deviance that was so closely associated with these practices mere decades ago (Stirn, 2003). In fact, a socially acceptable form of body modification — plastic surgery — erases stigmatizing characteristics by changing the appearance and function of the body (Johnson and Whitworth, 2002).

The varied forms of body modification noted are increasingly being termed body art — art that is made on, with or constituted by the body (Pitts, 2003). While body art is often framed as intentional body modification, I expand the concept of body art to include reclaimed unintentional acquisition of non-normative embodiment, such as that brought on by a physical impairment. Including impairment in the concept of body art transgresses the standards and boundaries of what is socially perceived to be beautiful and reflective of agentic individuals.

One of the more popular invasive methods of engaging in body art is cosmetic surgery. According to the American Society of Plastic Surgeons (2010), in 2009 about 12.5 million procedures were completed in the United States. From 2000 to 2009, cosmetic surgery procedures have gone up by 69% (American Society for Plastic Surgeons, 2010). Cosmetic surgery procedures range from outpatient procedures to decrease wrinkles in the skin through the injection of Botox to inpatient surgical procedures to increase the size of one's phallus. Cosmetic surgery offers the ability of molding the body to transform or transcend embodiment that does not align properly with an individual's feelings or identity. In essence, it presumes a culturally defined beautiful person may be lurking inside a body deemed ugly. Cosmetic surgery often provides a method to erase racialized, gendered, and disabling body markers in a way that serves to normalize the body and erase features that provoke stigmatization. Erasing disabling or disfiguring features through cosmetic surgery is often recommended for mental health purposes regardless of the inherent risks of surgery because it is assumed to enhance the nebulously defined "quality of life."

Cosmetic surgery offers a promise that a person can conform to the cultural conception of what is understood as normal, beautiful, and, in many cases, Euro-American. The growing social acceptance of modifying the body through cosmetic surgery is bound to cosmetic surgery discourse. Cosmetic surgery discourse reinforces the socially constructed notion of the connection between the non-marked body, mental health and competency (Haiken, 1997; Jordan, 2004), an idea that further posititions an aesthetically perfect body as an indicator of physical, mental and moral health. This concept is fleshed out in disability studies by situating the disabled bodymind as a marker for poor mental health, incompetency and amorality.

The more conventionally recognized method of engaging in body art includes actions, such as tattooing and piercing that shift the body away from the normative standard of beauty and embodiment and instead promote gaining agency or control over one's body. One of the founders of this new body art discourse and the leader of the Modern Body Modification Movement, Fakir Musafar, claimed that:

One thing is clear, we had all rejected the Western cultural biases about ownership and use of the body. We believed that our body belonged to us… [not to] a father, mother, or spouse; or to the state or its monarch, ruler or dictator; or to social institutions of the military, educational, correctional, or medical establishment (quoted in Pitts, 2003, p. 9).

Although not always the case, this body ownership rhetoric is often used by individuals who feel that they lack agency because some form of oppression strips them of social power, such as that resulting from socially sublimated manifestations of ability, gender, and race (Pitts, 2000).

Feminist scholar Shelia Jeffreys (2000) critiques the claim that agency can be spurred through body modification. She asserts that body modification practices are culturally and individually harmful, and her definition of harm is much in line with its codification in the Hippocratic Oath. Further, Jeffreys (2000) argues that the practices are socially legitimized through rhetorical strategies that construct them as means to achieve social liberation and conform to socially constructed meanings of beauty. Her claim builds on feminist critiques of other practices that mold the body to conform to standards of ideal beauty appealing to the male gaze, comparing body modification to wearing high-heeled shoes and to foot-binding (2000). Thus, for Jeffreys, body modification is a means for oppressed people to concede to their own domination by constructing their bodies as sites associated with the prime value on physical attributes.

But Jeffreys' contention denies various positive aspects of body modification. Her claim denies the multiplicity of meanings of body markings that people construct for themselves and the sense of community identity that is noted in body marking (Riley, 2002). In her attempt to expose gendered social institutions that promote body modification, Jeffreys denies individual agency and reduces the desire for body modification to a complete lack of ability to choose bodily fate. Thus, she supports normative gendered body discourse, despite her attempt to critique agentic bodies. Additionally, Jeffreys conflates all forms of body modification — ranging from cosmetic surgery and tattooing to self-cutting — into one pathologized category. Like Musafar (2003), I view body modification in a different light than Jefferys, as I have the desire to respect expression through body modification.

Both elective and non-elective body modifying practices have no intrinsic meaning but should be viewed as distinct because they conjure different socio-historical meanings. Elective body marking can be seen as an act of resisting or conforming to the hegemony of embodiment; whereas non-elective body marks, such as disabilities, are often culturally construed as a signal of a degeneracy and repugnancy (Garland-Thomson, 1996). The culturally constructed grammar of embodiment creates "rules about what a body should be and do" (Garland-Thomson, 1996, p. 6). If the grammar of embodiment were applied to body art, any form of body modification signifying disability would be deemed non-meritorious and socially abhorrent. Given the denigrated cultural status of disability globally, perhaps most evident in rampant poverty and violence experienced by disabled people, it makes sense that it is difficult for most people to fathom that a person would want to intentionally acquire a disability (United Nations, 2006).

Re-Viewing the Responses to Transability

O'Connor and other vocal transabled individuals actively seek to restructure the social understanding of transability so that transabled people may attain surgical intervention to reconcile their internal identity with their bodies. Transabled people seek to shift the public understanding of their identity from the pervasive view that transability is a paraphilia. According to the Diagnostic and Statistic Manual of Mental Disorders IV (DSM), the diagnostic standard for psychiatrists and psychologists, a paraphilia entails aberrant sexual behavior that serves as the "sole means of sexual gratification for a period of six months and must cause social or other functional impairment" (1994). Physician and sexologist Charles Moser (2001) problematizes this understanding of paraphilias because it perpetuates negative views of sexuality. Moser (2001) particularly critiques applying the paraphilia label to forms of sexual expression that deviate from the narrow realm of socially permissible activities because many of these acts are consensual and safe. Additionally, labeling different identities, such as transgender and transabled identities, as paraphilias erroneously conflates identity with sexual desire.

There may be credence to the notion that transabled people derive sexual satisfaction by achieving a desired form of embodiment. After all, some people are attracted to people who mirror their own embodiment. Infamous psychologist and sexologist John Money and his colleagues (1977) provided the first description of transability in his account of two individuals who demanded elective amputation of healthy limbs. Money and his colleague defined the subjects' desire for amputation—categorized as a paraphilia—as something spurred purely by sexual desire (Money et al, 1977). Money (1986) labeled people with the desire to amputate their limbs as apotemnophiliacs — those with "amputee love." It is useful to parse out the difference between those who fetishize disability and those who need it to reconcile their sense of self. Feminist disability studies scholar Alison Kafer (2000) examined the desires of 'devotees'— individuals who have an attraction or fetish for people with amputations or other disabilities — through interviews and attendance of one of their large national conferences. Kafer offers a complex understanding of devotees, in which she affirms some positive experiences that disabled women have with devotees. She also explicates common negative responses some disabled women have by stating: "many women with disabilities have had frightening encounters with disability fetishists, including being followed and photographed without permission. Other amputees, including myself, have had their names and physical descriptions disseminated through the devotee community without their knowledge or consent" (Kafer, 2000.)

Today many people dispute the pathologization of the transability identity arguing that those who need to be disabled are doing so to achieve their internal identity not sexual gratification. Some outspoken transabled people, including those featured on O'Connor's blog forum Transabled.org, call for transability to be deemed a legitimate identity group endowed with surgical rights. To achieve an identity rights model for transability, O'Connor advocates a complicated understanding of transability, one that is both medicalized and socially embraced. He explained that this is why he uses the labels 'transability' and 'BIID' interchangeably in conversation and in his writing. However, there is a subtle distinction between transability and BIID. Transability, "as a label, requires more thought because it calls for depathologization of this identity whereas BIID offers the benefit of a medical label" (personal communication, 2008).

O'Connor argues that the medicalization of transabled people would come to fruition through classifying transability as a mental disorder and including it in the DSM. His rationale hinges on his belief that society is not ready to embrace people needing disability and a mental health label may aid transabled people by providing a pathway to a cure. He stated the medicalized label and path to treatment would assuage the trouble so many have in understanding the need for disability. "It is easier to accept someone saying, 'I need to be paralyzed,' if that is wrapped up in the idea that is a 'psychological condition.' It is easier to understand that there is no control… even though it's in [my] head, it's not shakable" (personal communication, 2008).

The approach of lobbying for medicalization to forge a rights movement for transabled people is quite ironic to many disabled and other "monstrous bodied" people — who actively work against medicalization. But when the Hippocractic Oath creates a barrier to seeking one's needed body, it can be logical to use medicalization as a path to a 'cure.' Without the body being constructed as diseased or pathological, there would be no need for a 'cure.' Therefore, if a transabled person can use the medicalization framework to define transability as a 'disease' then they can get 'treatment' — surgery. It is necessary for the psychological and psychiatric communities to diagnosis this disease, before surgeons can ethically engage in transability interventions. Thus medicalization occurs in two steps. Transabled people need to acquire a label of disease to then procure a 'cure' safely.

O'Connor actively communicates with several of the leading scholars focused on transability in the hopes that they possess the power to provide a way for transabled people access to the surgeries they need. One such person is DSM-5 editor (due out in 2013) and one of the leading scholars in transability, Dr. Michael First. He argued that BIID has been inaccurately classified as a form of body dysmorphic disorder and as a paraphilia. He claims that people with BIID do not see their limbs as defective or ugly — how a person with body dysmorphic disorder would view their body (First, 2005). Instead, those with BIID see their limbs or various abilities as extraneous. While O'Connor did not participate in the study (he does not seek amputation), he concurs with First's conclusion by stating that his ability to walk is superfluous (personal communication, 2008). If BIID were included in the DSM, transabled people would be better equipped to seek the help they need to be content in their bodies. As an editor of the upcoming DSM-5, First has the power to recommend the inclusion of BIID into the manual and he is exploring whether it should be included.

The limited number of recorded surgical interventions that have been performed to aid transabled people have been successful (BBC news, 2000). Scottish doctor Robert Smith made international headlines in 2000 when he performed two elective amputations. The hospital he worked for stopped him from completing a third elective amputation of a healthy limb but allowed him to retain his position with hospital (Johnston and Elliot, 2002). Smith defended the procedures claiming that his patients suffered from severely disabling conditions that could have resulted in their suicide without surgical intervention and they appeared completely satisfied after their amputations. One individual who received an amputation surgery stated, "I have happiness and contentment and life is so much more settled, so much easier. I have not regretted the operation one bit" (quoted in Johnston and Elliot, 2002). Smith claimed he has no regrets either and maintained it was the most satisfying operation he ever performed. He stated he performed the amputations because he was convinced that psychiatric help would not cure their desire to be amputees, citing surgery as an accepted treatment for some transgender people (BBC news, 2000).

The Role of Devaluing Disability in Pathologizing Transability

A glaring issue that prevents transabled individuals from accessing the surgeries they need is the presumption that no one could ever want or need to have a disabled body. A critical disability studies lens is lacking in many of the pieces on transability or BIID to date. This theoretical framework provides for apt analysis on how removing a limb or severing the spinal cord upon request is deemed unethical 'harm' because of the historically denigrated status of disability. The Congressional facts included in the Americans with Disabilities Act (1990) posit that:

People with disabilities are still, far too often, treated as second class citizens, shunned and segregated by physical barriers and social stereotypes. They are discriminated against in employment, schools, and housing, robbed of their personal autonomy, sometimes even hidden away and forgotten by the larger society. Many people with disabilities continue to be excluded from the American dream (ACLU, 2008).

These facts make clear that the state of being disabled in America is one fraught with issues of stigmatization, exclusion and the devaluation of anything that deviates from perceived able-bodiedness (i.e. ableism). While I have done considerable work divesting my own internalized ableism and restructuring my view of disability through active engagement in disability culture and studies, I continue to wonder why people desire disability. I have come to the conclusion that part of my difficulty in reconciling why someone would want to be disabled stems from my own internalized ableism. I have been socialized in this culture that devalues the status of disability and exalts able-bodiedness, thus it makes sense that often I catch myself perpetuating the mainstream discourse of disability (even regarding the perception of myself) — that people with disabilities are somehow "damaged, defective and less socially marketable than non-disabled persons" (Susman, 1994, p. 18).

Part of the effect of internalized ableism can manifest in the need to search for a cure for disability, rendering intentional acquisition of disability seem even more bizarre. Certainly, there is more than internalized ableism affecting the ability of many disabled people to embrace transability. Many of us are justly troubled by the option to choose when to perform disability before it is surgically made permanent — like Sean walking around his home yet not believing it should be included in his narrative because it is not relevant. This selective performativity feels disingenuous and even infuriating to some disabled people because many of us do not get the option to take time off from disability. Additionally, the performance of disability harkens simulated activities in which nondisabled people ride in wheelchairs or walk blindfolded in order to presume knowledge about the disability experience. Such activities are largely panned by the disability community because they seem to make the experience of impairment a game and do not provide insight into the experience of ableism.

One of the leading scholars categorizing transability as a paraphilia is Dr. Richard Bruno, a clinical psychophysiologist, expert on disabling conditions and, interestingly enough, a wheelchair-user. Bruno (1997) explained that the idea that a nondisabled person could actually be disabled internally is "too difficult to justify, there being no naturally-occurring state of disability that corresponds to the two naturally occurring genders" (p. 251). There are two key flaws in Bruno's assertion. First, the claim that there are only two naturally occurring genders is fallacious. Biologist and gender studies scholar Anne Fausto-Sterling (2000) demonstrates how dichotomous categories of sex are social constructs; sex is biologically variable, resulting in many sex morphologies that deviate from binary cultural depictions of sexed bodies. Also, there are multiple manifestations of genders. Fausto-Sterling explains that the idea of binary sex is rooted in the biological process of fetal sexual differentiation, is influenced by chromosomal makeup, and is assigned based on external reproductive organs; whereas gender reflects an individual's self-conception and presentation of feminine, masculine or a mixture thereof. Additionally, feminist philosopher Judith Butler (1993) asserts that gender should be viewed as a performance that can foster meaning only through repetition and citational practice to the discourse of gender. Performing a culturally produced discourse does not make an attribute natural.

Bruno also fails to see disability as a natural part of life, which is troubling considering his professional expertise and wheelchair use. He supports the medical model of disability by conflating disability and impairment. Disability studies scholar Michael Oliver (1990) argues for a shift from the medical model of disability to the social model of disability, which separates impairment from disability. The medical model posits disability as a personal issue, in which the only remedy is a somatic cure rather than a restructuring of society. The social model shifts the meaning of disability from 'a problem of the individual' to a problem of the ableist society; society is the disabling factor. In this paradigm, impairment is the limitation one has in ability whereas disability is a cultural construct devaluing people who have impairments. Disability should then be understood as a social issue, in which society disables people by erecting attitudinal and structural barriers to the lives of people with impairments.

The assertion that disability is not natural is a powerful way to institutionalize the notion that nondisabled people are the norm, they are superior to disabled people, and that no one should ever want or need a disabled body. Both Bruno's claim that disability is not natural and the assumption that people should never want to be disabled are examples of the institution of compulsory able-bodiedness. Queer disability studies scholar Robert McRuer (2002) explains that the institution of compulsory able-bodiedness is similar to the institution of compulsory heterosexuality. Just as heterosexuality is constructed as a normative experience, everyone is socialized to believe that "able-bodied identities, [and] able-bodied perspectives are preferable and what we all, collectively, are aiming for" (McRuer, 2002, p. 93). The systems of compulsory heterosexuality and compulsory able-bodiedness obscure what is deemed to be non-normative by "covering over, with the appearance of choice, a system for which there actually is no choice" (McRuer, 2002, p. 92). These systems construct and perpetuate what is deemed socially meritorious.

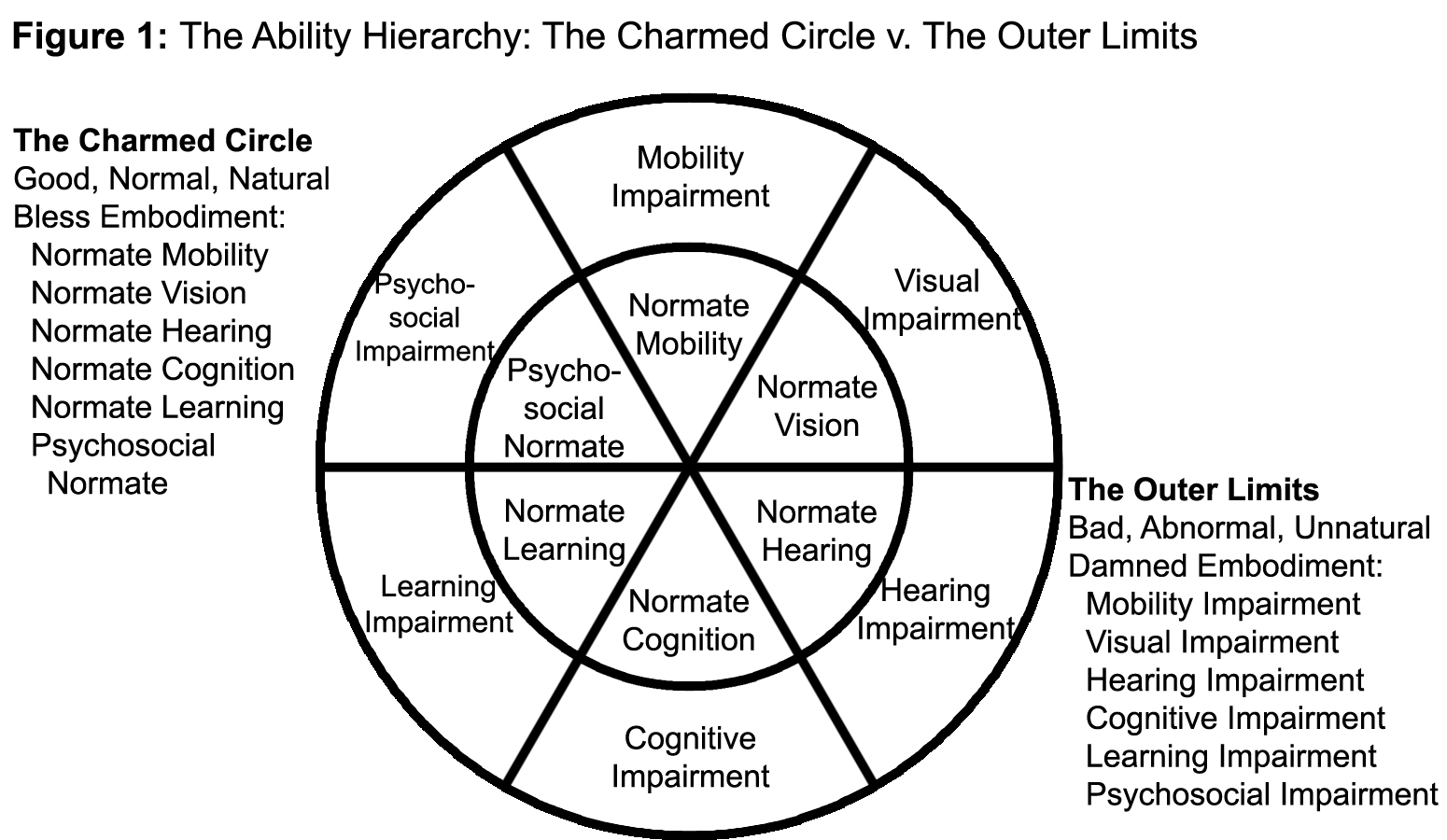

Within the value systems surrounding ability and sexuality, social hierarchy regards some aspects of human experience a violation of the rules of nature. Cultural anthropologist Gayle Rubin (1999) argued that through law, religion, psychiatry and popular culture, norms of sexuality rationalize privileging those who fit into the normative category and those who do not. The hierarchy of ability operates much in the same way that the hierarchy of sexuality works, with various institutions defining and enforcing compulsory able-bodiedness. To illustrate this idea of a sexual hierarchy, Rubin designed a diagram of the charmed circle of sexuality. The inner part of the circle represents the institutionally sanctioned and privileged aspects of sexuality, such as heterosexual, monogamous, non-commercial, and procreative sexualities. The outer part of the circle includes the non-normative aspects of sexuality that are deemed to be abnormal and unnatural such as homosexual, non-monogamous, commercial, and non-procreative sexualities.

Using a similar framework as Rubin, I created a charmed circle of ability to illustrate ability privilege (Figure 1). The examples of impairments in the outer limits of the charmed circle of ability illustration are not meant to be an exhaustive list of possible impairments. The outer limits of the charmed circle of ability have the same meaning as in Rubin's circle: they are considered bad, abnormal, unnatural and damned forms of embodiment. The outer limits of the charmed circle of ability include psychosocial impairment, cognitive impairment, visual impairment, hearing impairment, mobility impairment, and learning impairment. The charmed circle of ability — the good, normal, natural, and blessed forms of embodiment — includes psychosocial normate, normate cognition, normate vision, normate hearing, normate mobility, and normate learning. The word 'normate,' coined by feminist disability studies scholar Rosemarie Garland-Thomson (1996), operates like the term 'normative' in that it calls attention to privilege associated with the socially constructed concept of normal.

The charmed circle of ability is not an attempt to construct a binary in ability but is instead a tool to illustrate, just as Rubin did, the aspects of ability that are privileged and deemed natural and normal in our culture. Disability and ability do not operate as polar opposites in humanity. The categories of embodiment based on ability are never static. If society acknowledged this reality, we would all understand the meaning of disability as a natural form of embodiment and ability as just a temporary illusion of embodiment. As notable disability activist and subject of an Academy Award winning film Breathing Lessons (1997) Mark O'Brien stated: "Everyone eventually becomes disabled, unless they die first. How much more natural can you get?" (quoted in Aquilera, 2001).

We, as a culture, need to step away from the narrow conception of what we deem normative embodiment because it is truly oppressive to countless people. The culturally produced and "perpetuated standards [such] as 'beauty,' 'independence,' 'fitness,' 'competence' and 'normalcy' exclude and disable many human bodies while validating and affirming others" (Garland-Thomson, 1996, p. 7). The institution of compulsory able-bodiedness harms everyone by pushing the illusion that everyone should want to be able-bodied and anything else is undesirable and worthless. These value systems of embodiment do nothing but create more social issues, such as body dysmorphic disorder.

Disability as Body Art

The radical step I consider as a mode to destruct some of the barriers in the lives of transabled and disabled people is to restructure the meaning of disability as a valued form of embodiment and as art. Including transability within the spectrum of body modification provides a useful point of departure to begin to consider disability as body art. Generally, there is a sense of intentionality when body modification is deemed body art but this definition can be expanded to include those who embrace disability as a valued aspect of their personhood. In researching this topic, I came across an article featuring famous amputee pinup model Amina Munster and Ella Earp-Lynch, a woman with burns on one third of her body. "Missing Parts" (2005) detailed body modification that both women had incurred in their lives. Earp-Lynch outlined her burned skin with a thin tattoo line and stated that "I first started thinking of my scars as body modification when I began to see the beauty in them, and to feel that having them made me more, rather than less attractive" (Hyde, 2005). Her revolutionary view of aesthetic impairment subverts the dominant paradigm of disability as her assertion reframes the meaning of impairment or disfigurement as a form of art.

It is a powerful tool of resistance against ableism to think of disability as art, particularly in a culture that consistently demands compulsory able-bodiedness. There is so much to value in disability. Disability is a great pedagogical tool to illustrate that the United States ideal of independence — commonly referenced as the "boot-strap narrative" (e.g., with enough effort anyone can be successful and self-sufficient, even when navigating interlocking systems of oppression) — is a farce, as many disabled people need help. Moreover, many nondisabled people assert that they want and even need to help disabled people. While it may be easy to dismiss the argument that nondisabled people need to help others on the basis of paternalism, there is something truly valuable about giving to others. There is transference of positive energy between people who help each other; both the helper and the helpee provide each other with something valuable. Additionally, living with an impairment, and its attendant social stigma, necessitates creativity in negotiating everyday life. Disabled people must modify the grammar of embodiment to survive and thrive in a world constructed for able-bodies. Disabled performance artist and poet Neil Marcus (1993) perhaps most aptly states this idea in his well-known quote: "disability is not a 'brave struggle' or 'courage in the face of adversity'… disability is an art. It's an ingenious way to live."

Reconciling Transability

Interrogating the boundaries and meanings of body art is an excellent catalyst to re-view disability and work to see our embodiment as art. But what does all this mean for transability? Is the appropriation of disability signifiers by transabled people art or are they simply 'wearing' disability? This query borrows from the Oscar Wilde quote opening this piece — as it speaks to one of the central questions lingering with transability: are transabled people playing disabled or are they really disabled? Perhaps unanswerable, the question leads to others: what are the boundaries of disability? Are people who experience disability temporarily not truly disabled or not disabled enough to be authentic? And who has the authority to determine the authenticity of another person's identity? Also, why are so few disabilities desirable? In my research and discussions with O'Connor, I learned of no one who needed a developmental disability, a traumatic brain injury, mental health disabilities, etc. What does this say about the hierarchy of disability or which disabilities have the best performance factor?

I learned through the process of researching transability and getting to know transgender people that I really do not know who someone (including myself) is internally and should not have a say on whether people should be able to modify their bodies or not. I encourage questioning the uneven application of the Hippocratic Oath and I contend ableism is at the root of the idea that disability is harm. But I also have significant reservations about embracing transabled people into the disability community. It is quite problematic that transabled people, pre-transition, can 'take off' disability at will. Prominent disability blogger Wheelchair Dancer (2006) passionately discusses the problem of performing disability publicly but not always contending with disability by stating:

I am angry that these people parasite off the civil rights that were so hard earned because disability, for them, is a choice… I caught one pretender asking how a 'wheeler' could manage a certain journey on the NY subway. This just got my goat… [T]he times I have been caught when an elevator is broken, when I have risked my health to drag myself upstairs, had to ask for help to carry my chair, when I have gone deliberately out of my way because I have caught the wrong train and the next 12 stations are inaccessible and I cannot even consider walking that day. All this? And this person is expecting one of us to respond so she can fake being part of our world? (I googled her and found her at a pretender site). She doesn't live the daily struggle of trying to get a taxi, of things being out of reach, inaccessible and if she does experience them, they are a pleasurable part of her world. Something she can interpret as authentic disability experience.

My hostility toward those who perform disability has not quite reached the level that Wheelchair Dancer expresses in her blog, I believe in part because I have spent so much time talking to O'Connor. In speaking with him over the years, transability became humanized. I empathized with his struggle and pain. It was a similar narrative of pain that I heard from some transgender and gender variant friends. I empathized with his pain and tried to see the transability struggle as analogous to being transgender because I knew my friends were speaking their truth about needing to transition. Nevertheless, I recognize and feel absolute infuriation at the idea of disability being somewhat of a game that is played out in public to obtain emotional or psychological satisfaction.

Beyond recognizing my internalized ableism and the irksome nature of performing disability, the question remains: where do transabled people fit into the disability world? The literature on the topic points to the fact that transabled people are contending with a mental health issue. This fact alone makes them a part of the disability community but perhaps not in the way that they want. The proximity to a devotee-type fetishization of disability, however, makes the acceptance of transability as even a mental health issue a bit too muddled. How transabled people define themselves in relation to the medical establishment appears to be very much an ongoing process, that may shift the paradigm around medicalizing disability. This issue is apparent by the need for a medical label to reach an identity, which is the antithesis of the work the disability community has worked on regarding the shift to the social model of disability. Additionally, transability raises a fascinating question about why there is no literature positing that cure or other medical interventions with/on disabled people are efforts to make disabled people transabled (or "well"). Though I have more questions than answers now about transability, I ask that we consider viewing transability through the lens of disability as art. In doing so, transabled people may find a home in the disability community — so long as they bring with it a full commitment or artistic integrity to the disability experience.

Works Cited

- American Civil Liberties Union (2008). Disability Rights. Retrieved on April 2, 2008 from: http://www.aclu.org/disability/index.html

- American Society for Plastic Surgeons. (2010). 2009 Quick Facts: Cosmetic and reconstructive surgery trends. Retrieved on January 20, 2011 from: http://www.plasticsurgery.org/Documents/Media/statistics/2009quickfacts-cosmetic-surgery-minimally-invasive-statistics.pdf

- Aquilera, R. (2001). Disability and Delight: Staring back at the devotee community, BENT. Retrieved on April 2, 2008 from: http://www.bentvoices.org/culturecrash/aguilera_disability_delight.htm

- Buno, R. (1997). Devotees, Pretenders and Wannabes: Two cases of Factitious Disability Disorder, Sexuality and Disability, 15(4).

- Butler, J. (1993). Bodies that Matter: On the Discursive Limits of "Sex." New York: Rutledge.

- Elliot, C. (2002). A New Way to be Mad, Atlantic Monthly, 76.

- Fausto-Sterling, A. (2000). Sexing the Body: Gender Politics and the Construction of Sexuality. New York: Perseus Books.

- First, M. (2005). Desire for amputation of a limb: Paraphilia, psychosis, or a new type of identity disorder, Psychological Medicine, 35.

- Garland-Thomson, R. (1996). Extraordinary Bodies: Figuring Physical Disability in American Culture and Literature. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Gilman, D. (2002). Body Work: Beautify and Self-Image in American Culture. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Haiken, E. (1997). Venus Envy: A History of Cosmetic Surgery. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Hyde, G. (2005). Missing Parts, BMEZINE. Retrieved on April 2, 2008 from: http://www.bmezine.com/news/steppingback/20050209.html.

- Jeffreys, S. (2000). 'Body Art' and Social Status Cutting, Tattooing and Piercing from a Feminist Perspective, Feminism & Psychology, 10(4).

- Johnson, D. & Whitworth, I. (2002). Recent developments in plastic surgery, BMJ. Retrieved on April 2, 2008 from: http://www.bmj.com/cgi/content/full/325/7359/319.

- Johnston, J. & Elliott, C. (2002). Healthy Limb Amputation: Ethical and Legal Issues, Clinical Medicine, 2(5).

- Jordan, J. (2004). The Rhetorical Limits of the 'Plastic Body,' Quarterly Journal of Speech, 90(3).

- Kafer, A. (2000). Amputated Desire, Resistant Desire: Female Amputees in the Devotee Community, Society for Disability Studies, presentation. Retrieved on April 2, 2008 from: http://www.disabilityworld.org/June-July2000/Women/SDS.htm

- Lawrence, A. (2006). Clinical and Theoretical Parallels Between Desire for Limb Amputation and Gender Identity Disorder, Archives of Sexual Behavior, 35(3).

- Marcus, N. (1993). Disability Social Project. Retrieved on April 2, 2008 from: http://www.disabilityhistory.org/dshp.html

- McRuer, R. (2002). Compulsory Able-Bodiedness and Queer/Disabled Existence, In Disability Studies: Enabling the Humanities, eds. Sharon Synder, Brenda Jo Brueggeman, and Rosemarie Garland-Thomson. New York: The Modern Language Association.

- Money, J., Jobaris, R. & Furth, G. (1977). Apotemnophilia: Two Cases of Self-Demand Amputation as a paraphilia, The Journal of Sex Research, 13(2).

- Money, J. & Simcoe, K. (1986). Acrotomophilia, Sex and Disability: New Concepts and Case Reports, Sexuality and Disability, 7(12).

- Moser, C. (2001). Paraphilia: A Critique of a Confused Concept, In New Directions in Sex Therapy: Innovations and Alternatives, eds. P.J. Kleinplatz. New York: Brunner-Routledge.

- Oliver, M. (1990). Politics of Disablement. Basingstoke, England: Macmillin.

- O'Conner, S. (2007). A quick recap of my life up to date, Transabled.org: Talking about Body Identity Integrity Disorder — Just another disability! Retrieved on April 2, 2008 from: http://transabled.org/thoughts/sean-thoughts/a-quick-recap-of-my-life-up-to-date.htm.

- O'Connor, S. (2009). My life with BIID, In Body Integrity Identity Disorder: Psychological, Neurobiological, Ethical and Legal Aspects, eds. Stirn, A., Thiel, A., & Oddo, S. Lengerich, Germany: Pabst Science Publications

- O'Conner, S. (2008-2011). Personal communication.

- Pitts, V. (2000). Visibly Queer: Body Technologies and Sexual Politics, The Sociological Quarterly, 41(3).

- Pitts, V. (2003). In the Flesh: The Cultural Politics of Body Modification. New York: Palgrave.

- Riley, S. (2002). A Feminist Construction of Body Art as a Harmful Cultural Practice: A Response to Jeffreys, Feminism & Psychology, 12(4).

- Rubin, G. (1999). Thinking Sex: Notes for a Radical Theory of the Politics of Sexuality, In Culture, Society and Sexuality: A Reader, eds. Parker, Richard & Peter Aggleton. Los Angeles: UCLA Press.

- Stirn, A. (2003). Body piercing: medical consequences and psychological motivations, The Lancet, 361.

- Surgeon defends amputations, BBC News. (January 2000). Retrieved on April 2, 2008 from: http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/scotland/625680.stm

- Susman, J. (1994). Disability, Stigma and Deviance, Sociology, Science & Medicine, 38(1).

- Wheelchair Dancer. (2006). Disability Porn, the Observer, Wheelchair Dancer. Retrieved on April 2, 2008 from: http://cripwheels.blogspot.com/search?q=BIID.

- United Nations. (2006). Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities: Some facts about persons with disabilities. Retrieved on April 2, 2008 from: http://www.un.org/disabilities/convention/facts.shtml

Endnotes

-

Sean O'Connor is the self-chosen pseudonym of a non-physically disabled man who needs a spinal cord injury. He is the webmaster, founder and author of a blog website, www.transabled.org, and an information clearinghouse website, www.biid-info.org.

Return to Text