Introduction

Autistic people are generally seen as lacking in ability to share common interests with others, disconnected from social participation and fellowship, and inaccessible to social transmission of behaviors and attitudes. These are core aspects of what has been described as autistic "aloneness," "withdrawal," and "disconnectedness," autistic people "living in their own worlds," being "trapped" inside "shells" or behind "invisible walls," and many similar terms used by neurotypical (NT) people to describe their perception that autistic people are unable to be "together" with other people. (For examples see Frith, 1992; Maurice, 1994; Kaufman, 1995; Claiborne Park, 1968; Tustin, 1990).

For autistic people the situation is not so clear-cut. Some of us, at some times in our lives (generally early childhood), really aren't aware of other people or their activities or their attempts to connect with us. Others of us are aware of the people around us, but find them difficult or impossible to understand. Some of us have sensory sensitivities that make being around other people distressing to us, either because of the people themselves (unwanted touching, loud talking, perfumes and other overwhelming scents), or because of sensory features of the environments in which we encounter other people. Some of us aren't interested in the same things the people around us are interested in, and we don't have a natural impulse to take interest in things just because we observe that other people find them interesting. Some of us are keenly interested in other people and their interests and activities, but we don't know how to engage with other people around those shared interests.

By the time we reach adulthood, autistic people's experience of "togetherness" has likely consisted of some combination of: being intruded on by other people wanting us to engage with them, when we don't share that desire; being interested and curious about other people, but finding them confusing and overwhelming to be around; trying to engage with other people, and having frustrating and unsuccessful encounters; managing to engage "successfully" with other people, and finding ourselves drained and possibly even damaged as a result of what we had to do to "succeed."

After a lifetime of such distressing and discouraging experiences, it would be little wonder if autistic people did choose to withdraw from human contact. Yet during the past 20 years, facilitated in large part by the availability of the Internet, more and more autistic people have been reaching out and forming connections, creating community, and discovering our own styles of autistic togetherness.

As co-founder of Autism Network International (ANI, http://www.ani.ac) and as its coordinator since its inception in 1992, I have been blessed with the opportunity to witness much of this unfolding. To the best of my knowledge, ANI was the first autistic community to be created naturalistically by autistic people, and it remains the largest autistic-run organization to have regular physical gatherings of autistic people. I am primarily in a position to report about the culture that has developed within this particular autistic community. Other autistic communities, founded and populated by other "flavors" of autistics, may have very different cultures. I am more familiar with some of these than with others. Autistic connections have grown and expanded greatly since ANI was founded. There is now more autistic communicating and networking and socializing going on than any one person can keep track of.

Brief History of ANI

Autism Network International was founded in February 1992 by Donna Williams, Xenia Grant (formerly known as Kathy Lissner-Grant), and me (Sinclair, 2005). We had initially contacted each other via a penpal list maintained by a parent-run organization. Xenia and I had also briefly encountered each other, and a few other autistic adults, at mainstream autism conferences. But Donna's visit in 1992 was the first time we had been together, in person, in "autistic space": Xenia's apartment, where there were no NT people arranging the environment or setting the agenda (Williams, 1994).

Initially ANI consisted of a newsletter and a penpal list. The penpal list soon fell by the wayside due to harassment of several of our members by a very persistent stalker.

In late 1994 ANI launched our own Internet discussion forum called ANI-L. Publication of the printed newsletter became infrequent and sporadic as more people began communicating online.

Small groups of ANI members continued to meet in person whenever we could, often traveling long distances to spend a few days together at someone's home. ANI sometimes had exhibit booths at mainstream conferences, where members were able to spend time together (albeit under difficult sensory conditions and in pervasively negative atmospheres), and newcomers were able to find us.

In 1995 I was asked to develop a strand of sessions for "high-functioning" autistic people within a larger parent-oriented conference. I made it an ANI project in which other autistic people worked with me to plan what we called the ANI strand (not the "high-functioning autistic people's strand"). This conference marked the first time a large number of ANI members — not all of whom would generally be considered "high-functioning" — came together in person.

In many ways it turned out to be a horrible ordeal for the ANI members who participated, especially those of us who organized the ANI strand. There were persistent communication breakdowns with the main conference organizers. The conference venue was a sensory nightmare for many autistic people. Lodging was unaffordable for most of our members. Several autistic attendees (and all the ANI-strand organizers) complained of rude or condescending treatment by NT conference organizers or participants.

On the other hand, the time autistic people got to spend together was precious to many of us. People enjoyed it and wanted more of it. The presentations in the ANI strand were stimulating, meaningful, and valuable to many people, including quite a few NT parents and professionals who attended. We began to realize how much autistic people have to offer to ourselves and our peers.

And so we decided to organize our own autistic event, independent of NT directors or sponsors. In 1996 ANI presented the first Autreat (http://www.autreat.com): a retreat-style conference run by and for autistic people, designed to accommodate autistic people as much as possible, with presentations geared to the interests of autistic people. Autreat has been held every year since, with the exception of 2001.

A great many newer autistic forums have flourished on the Internet since ANI-L began in 1994. A number of local live-meeting social or support groups for autistic people have been founded around the world. Some larger organized autistic-run events for autistic people, such as Autscape in the UK (http://www.autscape.org/), Empowerment-Päivät in Finland (http://www.puoltaja.fi/blogi/vuoden-2009-empowerment-paivat-alkaneet), and Aspies e.V. Sommercamp in Germany (http://www.aspies.de/sommercamp.php), now exist or are being planned. While each group and each event has its own unique character, there is a significant amount of information-sharing and overlapping customs, as some of the same people participate in multiple events.

ANI was founded, and our major activities were developed, by a core group of early members who had certain characteristics in common: We were all highly verbal (though not necessarily fluent with oral speech) and comfortable with written communication (a built-in selection factor when most contact was via email); we tended to be more sensory-defensive than sensation-seeking; more prone to shutdown than to meltdown when overloaded; most of us did not have major difficulties with impulse control; we understood and respected personal and property boundaries. Whatever difficulties we had in functioning — and those difficulties might be quite severe, limiting our abilities to feed and care for ourselves — our difficulties did not generally interfere with other people around us.

The ANI community has thus developed to have a high reliance on written language as a means of communication, and to have customs and rules that place greater emphasis on protecting people's boundaries than on allowing complete freedom of self-expression. People who need to protect themselves from sensory and social overload are more likely to feel comfortable and supported by ANI's rules and customs, while people who need intense stimulation, and/or who struggle with impulse control, may find some of our rules uncomfortably restrictive. Over the years our community has expanded and our membership has become more diverse. We have tried to accommodate people's differing needs as best we can. ANI culture continues to change and evolve with the changing needs of our membership. And for people who find that ANI simply is not a good fit for their personal needs, there's a growing number of other options for autistic fellowship.

Being Autistic in NT Space

As previously mentioned, most autistic adults have experienced a lifetime of difficulties and disappointments with interpersonal connections. Being autistic among neurotypical people is likely to consist of not understanding what other people are doing, or why they're doing it, or what they expect us to do; not being understood when we ask questions or try to join in; being misunderstood and misinterpreted in hurtful ways (such as being accused of dishonesty or hostility based on lack of eye contact or "flat affect," or being perceived to be drunk, drugged, delusional, or even dangerous) (Debbaudt, 2002); being pressured or coerced to participate in activities we find uninteresting or even aversive; being excluded from activities we want to participate in; being criticized for, or disallowed from, expressing "odd" interests or engaging in "weird" behaviors (including some behaviors that are adaptive in helping us to be able to function); being deliberately bullied, ridiculed, or otherwise mistreated; being belittled or patronized by well-meaning but clueless people who think they're "helping" us; being subjected to noxious sensory stimuli as the price of social participation; and being expected to maintain a level and pace of participation that is overwhelming and draining for us.

On the other hand, there are benefits that NT people bring to social situations: They tend to be far more oriented than we are in social encounters. They know what to do (or at least they know how to fake knowing what to do). Sometimes NT people are willing to explain things to us and coach us. Many socially "successful" autistic people have learned the strategy of choosing one or more socially competent NT model(s) and relying on them for cues, even if those NTs are not actively coaching or are not aware that they're being used as orientation foci (or even, in fact, if they're fictional characters and not real people at all). NT people (real ones who are physically present) are likely to be able to predict other people's social needs. Sometimes they're even able to predict autistic people's social needs, and provide us with helpful prompts and cues. Most NT people are better than most autistic people at multitasking, and at remaining organized despite distractions and interruptions, and other manifestations of executive functioning. Even the most disorganized and distracted NT people usually notice when they're hungry, and remember to eat! Autistic people may not notice or remember such basic self-care needs. NT people can provide useful cues and reminders.

Being Autistic in One's Own Space

Autistic people who are fortunate enough to have their own private spaces, especially adults who have their own homes but to some extent also people living in shared homes who have their own rooms, have a refuge from many of the stresses of being in NT space. People in their own personal spaces have a great deal of control over what happens in those spaces. Within the limits of laws, zoning ordinances, and any rules set by landlords, people are free to arrange the environments the way they want them. I'm free to paint all my walls purple, replace eye-stabbing bright lights with low-wattage bulbs, play the same music over and over and over and over and over and over and over again (provided I don't play it so loudly that it disturbs my neighbors), and play with "age inappropriate" action figures, because it's my own home and nobody else gets to come in and dictate what I do in it. In fact with very few exceptions, nobody else gets to come in at all, unless I choose to let them in. Having one's own space means having control over the space itself, over what one does in the space, and over who has access to the space. There are minimal limits on what one may do in one's own space. One can stim, tic, perseverate, stay up all night, sleep all day, wear the same clothes for days at a time, or wear no clothes at all — one can do any number of things that most other people would find annoying or even disgusting, and if there's anyone else around to notice, it's because there's a mutual agreement and a shared comfort level in having that person in one's space.

But with that increased freedom in one's own space comes decreased external structure. Many autistic people have considerable difficulty managing routine self-care and maintenance functions without someone to remind and assist us. We can easily find our spaces and our lives devolving into chaos if we live completely on our own, with no one else coming into our space (Smith, n.d. a; Zaks, 2006).

Being autistic in NT space and being autistic in one's own space both involve being "the only one" — the only autistic person in the environment. This is one major way in which being autistic in shared autistic space differs from being autistic anywhere else.

Autistic Space vs. Places for Autistics

Some autistics have experienced situations in which autistic people are in the majority, but NT people are still in charge of creating structure and setting the agenda. Special education classrooms, sheltered workshops, day hab programs, residential facilities, specialized group therapy programs, and "special" leisure/recreational programs for autistic people are all examples of environments that NT people create for autistic people, according to NT people's perceptions of what autistic people need.

In the debate between proponents of inclusion and proponents of separate programs for autistic people, arguments in favor of special programs emphasize the benefits of having staff who are knowledgeable about the needs of autistic students/clients, and of having contact with autistic peers instead of being the lone autistic in a group of NTs (Sinclair, 1998; Broun, 1996). These can indeed be important benefits, regardless of who is directing and staffing the program. There are some NT educators and service providers who have good understanding of autistic people's needs and processing styles, and who provide excellent environments in which autistic people can learn, work, develop skills, and have a good time.

There are also some ignorant, misinformed, and misguided educators and service providers who create environments which can be very unpleasant and even harmful for autistic people (particularly for people who are "placed" in them involuntarily without being allowed a developmentally appropriate degree of choice) (Baggs, 2006a; Judd, 2009, Shapiro, 1991). Autistic processing is devalued and autistic functioning is undermined in these kinds of environments. At the same time people in such settings are struggling with those environmental impediments, they are surrounded by similarly stressed autistic peers who are suffering the effects of the same undermining and devaluation, and are reacting accordingly. People who experience such situations may develop negative associations about autism and about being in the company of other autistic people.

Whether good or bad, environments created and run by NT people are not autistic spaces, even if the majority of people within them are autistic. A good NT teacher, therapist, job coach, life skills trainer, or other service provider can certainly create an environment in which autistic people have positive experiences and learn useful skills. But even such positive and helpful environments still have characteristics of "NT spaces," because NT people are in charge and NTs are making the rules. The very fact that NTs are creating and managing a program or a service, for the benefit of autistic participants, conveys the perception that autistic people are helpless and dependent on NTs to take care of us.

In a shared autistic space, autistic people are in charge. Autistic people determine what our needs are, and autistic people make the decisions about how to go about getting our needs met (Schwarz, 1999; Shapiro, 1991).

Being Autistic Together

Autistic spaces, whether small informal gatherings at people's homes, online discussion forums, or major autistic-run events like Autreat, are meant to provide autistic people with the benefits of contact and participation with other people, while accommodating autistic needs that can make NT spaces so difficult.

Being autistic in shared autistic space may be easier than being autistic in NT space or in one's own personal space — or it may be harder. People sometimes come to autistic space expecting a kind of utopia where there will be no interpersonal or environmental difficulties. In actuality it simply has some different difficulties.

One frequent difficulty that autistic people may have in their initial encounters with autistic space is that things are unfamiliar. Being in NT space or in one's own space may present difficulties, but by the time we're adults, we've gotten used to living with those difficulties. Most of us have developed strategies to help us function to some extent. People often arrive at a shared autistic space not knowing what to expect, or, worse, having expectations that don't match the reality. Our familiar coping strategies, which serve us well in NT space, may not work so well among other autistic people. They may even backfire and be received negatively.

Why Autistic Space is Different from NT Space

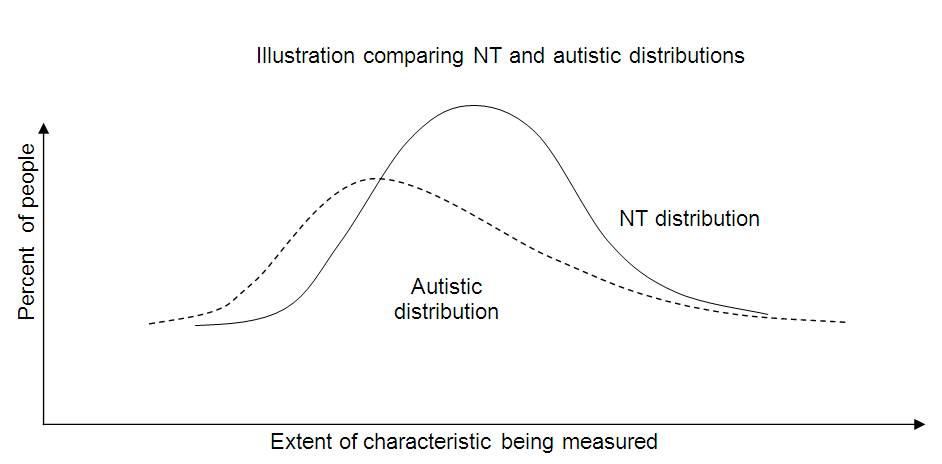

The reason autistic space is different from NT space is not merely that autistic people are different from NT people. Autistic people are also very different from each other (Spicer, 1998). In just about any area one can think of where humans vary, the range of variability among autistic people seems to be even greater than the range among NT people:

Sensory sensitivity and social interest may be the two best examples of this variability. The common stereotypes are that autistic people, across the board, are sensory defensive and are uninterested in social contact. If these stereotypes were accurate, it would be relatively simple to create comfortable autistic spaces. We would just have to develop customs and rules and environmental modifications so that there would be less sensory stimulation and less interpersonal contact than are the norms in NT environments.

The reality is that there are many sensory-defensive autistics who are easily overwhelmed by typical levels of stimulation in NT environments. But there are also low-registering autistic people who tolerate — even need — more intense stimulation than the most sensory-seeking NTs would find comfortable.

Moreover, "sensory defensiveness" is not uniform across sensory modalities. It is possible, for example, for someone to be easily overwhelmed by auditory stimuli but to seek out intense visual stimulation, or to be extremely tactile defensive but crave (and also create) a lot of loud sounds, or to avoid some types or ranges of visual/auditory/tactile/olfactory/gustatory stimuli while seeking out other types or ranges of stimuli, or any number of other combinations of sensory defensiveness and sensation-seeking within the same person.

This extreme autistic variability presents challenges in accommodating sensory needs in autistic space. The kinds of sensory stimuli that are hurtful to some autistic people may be necessary for others.

Similarly, autistic people have in common (by definition, as part of the diagnostic criteria for autism) abnormalities or "impairments" in communication and social interaction. But we're not all abnormal in the same ways. Our ways of interacting are different from NT norms — and also different from each other's! — and the amount of interaction we want also varies across an even wider range than it varies among NTs. We range from not wanting any social contact at all (which is the common stereotype, but rarely the reality), to wanting some social contact but needing more down time than most NTs (even introverted ones) need, to wanting an NT-normal amount of contact, to wanting or needing constant contact, even more than "normal" extraverted NTs can tolerate.

Creating comfortable autistic social space is not a simple matter of removing NT social pressures and expecting that autistic people will naturally leave each other alone. Even with no NT influences at all, some autistic people will seek out social connections in ways that feel intrusive to other autistic people, and some autistic people will assert their need for personal space in ways that feel rejecting to other autistic people. And given that we also differ from each other, at least as much as we differ from NTs, in our verbal and nonverbal communication styles, we are not automatically able to guess each other's preferences and needs.

Virtual vs Physical Spaces

It is no accident that the concept of "autistic space" and the roots of autistic community originated in cyberspace. For those of us who are comfortable with written communication, online contact offers the opportunity to meet and interact with other people while remaining at home in our familiar environments. We don't have to go out into noisy crowded public spaces and risk uncontrollable sensory assaults. We can take in and respond to communications at our own pace, instead of having to keep up with realtime conversation. We can participate in online discussions with large groups of people, and since we're only reading one email at a time, we can keep track of who's saying what. We can catch everyone's input if we want to, or choose which ones we want to read and which we want to filter out. We don't miss out on what one person is saying while we're listening to someone else. It's fairly easy online to filter out input from people we find uninteresting or unpleasant to hear from. And many of the communication pitfalls we encounter in face-to-face communication with NTs — being expected to understand nonverbal signals, having people try to read meaning into our own appearance and nonverbal behavior — don't exist in text-only communication. (It still boggles my mind when NT people complain about this as a drawback of online communication!)

Gathering together with other people in physical space, even at events such as Autreat which are carefully planned to accommodate autistic people, cannot help but include some of the difficulties and challenges that online communication avoids. Leaving home to attend a physical gathering means experiencing the stress of travel, followed by the stress of being in an unfamiliar environment over which we have much less control than we have over our personal spaces at home. Being around other people inevitably means being exposed to the behaviors and sensory stimuli that other people produce. Being in a shared space means being required to modify our own behavior to accommodate other people's needs. Being around a lot of other people at once means it is impossible to attend to what everyone is saying without missing anything. Attending a "community" event such as Autreat (as opposed to one's own private event where one can hand-pick who is invited) means possibly encountering people one doesn't know, doesn't understand, and/or doesn't like. In terms of interpretations (and possible misinterpretations) of nonverbal behavior, autistic people vary as much in our nonverbal communication as we do in other regards. Misunderstandings based on appearance and nonverbal behavior can be minimized through awareness of our differences, but autistic people are not immune to misinterpreting each other.

Leaving our familiar personal spaces to come together in autistic physical space is not always easy or comfortable. Those of us who make the effort to come together physically (at least those who keep coming back) do it not because it's easy and problem-free, but because the benefits we get from it are worth the difficulties and the discomforts.

Many of the characteristics of autistic physical space can be experienced as either benefits or hardships, depending on one's point of view. Challenges can become opportunities if one is prepared to approach them as exercises in self-discovery.

Challenges and Opportunities

Autistic Similarities

Some autistic people have written moving, dramatic accounts of immediately feeling "at home" among other autistics, having a natural sense of "belonging," and recognizing other autistics as "their own kind" of people (French, 1993; Williams, 1994; Cohen, 2006).

My own words to describe the 1992 visit with Xenia and Donna during which ANI was founded were "feeling that, after a life spent among aliens, I had met someone who came from the same planet as me." This "same planet" metaphor, along with metaphors about "speaking the same language" or "belonging to the same tribe," are very common descriptions used by autistic people who have had this experience of autistic space. One participant at the first Autreat in 1996 summed it up saying, "I feel as if I'm home, among my own people, for the first time. I never knew what this was until now."

For autistic people who have this kind of autistic-space experience, it is obviously a powerful and often life-changing experience. But it can also be profoundly disconcerting. Growing up autistic among NTs can lead to having a sense of identity and self-image formed around being "special" — the only person to have some particular autistic characteristic, the only person who has to struggle with some particular hardship, the only autistic person who has managed to achieve some particular accomplishment despite one's disability. NT society is inclined to treat disabled people with excessive pity for our difficulties and excessive admiration for our strengths, infusing our daily lives and routine activities with a melodramatic sense of tragedy over our problems and amazement over our successes (McNabb, 2001).

This feeling of "specialness" can be jarringly upset by encountering other autistic people who have a similar mix of autistic traits, have similar (or even worse) problems, and have attained similar (or even higher) achievements. In a genuine peer group, which most autistic people have never experienced, each person is unique, but no one is more "special" than anyone else.

The sense of "homecoming" and "belonging" among fellow autistics can also set people up to have idealized expectations of these newfound autistic compatriots. This is characteristic of the "immersion" stage of minority identity development (Helms, 1995), in which people embrace and idealize their own minority communities to the exclusion of other kinds of people. Inevitably this idealization is eventually followed by disappointment and disillusionment, when other members of one's own group turn out to have the same failings as the rest of the human race.

Autistic Differences

The great diversity among autistic people means that while some people have these powerful autistic-space experiences of encountering people "like ourselves" for the first time ever, other autistic people do not. People who come to an autistic space expecting that everyone will like them and everyone will be "like them," everyone will understand them, and everyone will be easy for them to understand and get along with, are likely to be disappointed. If the autistic people in that particular group happen to be very different from them, they may end up feeling even more alienated and out of place than they feel in familiar NT environments. This can lead some people to question their own status ("If I'm so different from these people, maybe I'm not autistic after all"), or to doubt other people's status ("You're not like me, so you're not really autistic and you have no business calling yourselves autistic"), or to devalue some subgroups of autistic people relative to others ("Autistic people who are like me are better than autistic people like the ones in this group who are making me uncomfortable").

Some autistic groups try to minimize such discomforts by limiting participation to only certain "types" of autistic people. I've heard of incidents in which autistic people were excluded from groups for being "too low-functioning," not verbal enough, or otherwise not conforming to that group's idea of the sort of autistic people it wanted as members (Baggs, 2006b; Smith, n.d. b).

ANI has taken a different approach. While our customs and our culture are heavily influenced by the shared characteristics that drew our early members to each other and enabled us to work together on building the infrastructure for community, we have always done our best to welcome and accommodate the widest possible range of autistic diversity (Autism Network International, n.d. a; Autism Network International, 2009). (This does not mean that we'd never exclude any autistic person for any reason. People can be, and occasionally have been, excluded from participation in ANI functions — on the basis of behavior that victimizes other people, not merely for being too different or too severely disabled. See Autreat Planning Committee, n.d.)

The real "magic" of inclusive autistic spaces, such as we strive for in ANI, is not that every autistic person can automatically expect to find other people who are like him or her. The real "magic" is that almost every autistic person — everyone who is able to participate without violating other people's boundaries — can expect to be accepted for who he or she is. Some typical descriptions of this experience are:

"This was the first place I wasn't criticized for being different."

"It showed me that being me was okay, and that my ways of doing things weren't 'wrong' or 'defective,' just different, and perfectly all right."

"For the first time, I had my less than 'normal' attempts at communication recognized, and also accepted."

"We loved the feeling of being accepted and liked for being ourselves!"

Note that being accepted for who one is does not require being surrounded by people who are just like oneself. This is reflected in one participant's reflection on the first Autreat: "Here people who could paint and draw equally shared experiences with those who can't hold a pencil or a brush. People who are very articulate equally shared experiences and understood those who could only jump or clap their hands or point to letters on a letter board or picture board to respond to a question."

The associated challenge is that one must also be prepared to accept other people for who they are: It's okay for you to be weird, which is liberating, but it's also okay for other people to be weird. That can be startling and disturbing if their weirdnesses are very different from yours.

Spontaneous Interaction

Autistic people may be less likely than NTs to spontaneously initiate interactions with anyone who happens to be nearby. Common complaints NTs have about autistics are that we seem unfriendly and standoffish and we don't express interest in other people (Meyerding, 1998; Aston, n.d.; Foden, 2008). Common complaints autistics have about NTs are that they seem pushy and demanding and they waste conversational energy on meaningless small talk (Sinclair, 1995; Muskie, 2002; Adam, 2009; WrongPlanet.net, 2008).

At autistic gatherings such as Autreat, there can be a tremendous amount of communication and interaction once people find a common point of interest. (Autreat presenters need to be prepared to limit questions and comments from the audience, or else be willing to accept the fact that they may get to cover only a fraction of their prepared material, because autistic participants get extremely participatory when our interest is engaged!) But there's not likely to be a lot of spontaneous initiation of social contact, particularly between people who don't already have an established social relationship.

This is an important factor for some autistic people's ability to be comfortable in autistic space. Many of us need undisturbed time to observe people and activities before we can decide whether or not we want to join in. Sometimes we'll decide to start participating after we've watched for a while. Sometimes we decide we don't want to participate, but we're still interested in watching what other people are doing. It's a great relief to be able to be among people, partaking of whatever aspects of the situation we're interested in, without pressure to do more socializing.

It can also be a great challenge for autistic people who are subject to getting stuck, and are used to relying on people around them to initiate and facilitate. If a person is hanging around in or near an NT social space without joining the group, someone will probably come over and invite the person to join in. Autistic people may come to rely on NTs to provide this kind of prompting, cuing, and initiation in social situations.

If a person is hanging around and not participating at Autreat or a similar autistic social space, other people will most likely just leave the person alone. Autistic people typically have a hard time attending to multiple people and things at the same time, so if we're attending to our own activity and to our interactions with other people who are participating in the activity with us, we may simply not notice someone sitting quietly off to the side. If we do notice, we can't assume the person wants to join in. We can't guess whether the person would welcome interaction or would feel intruded upon. Even if we suspect the person would appreciate some kind of interaction, we can't guess what kind of interaction would be welcome. Our own experience of unwelcome interactions has made most of us keenly aware of the pitfalls of trying to read other people's nonverbal signals!

For the person who does get stuck, and finds that nobody takes the initiative to come and help, there are many possible ways to process the experience as an opportunity. Some examples of how different people have processed this kind of experience at Autreat are:

I wasn't sure what to do or where to go or what was expected of me. I felt lost and very anxious. Then I realized that nobody was watching or judging me, and nobody cared whether or not I participated in the activities. I didn't 'have to' go anywhere or do anything unless I wanted to. I discovered that it's okay for me to take time to get my bearings, and it's okay to not know things, and it's okay to ask questions when I don't know what's happening.

or

I wasn't sure what to do or where to go or what was expected. I felt lost and anxious and helpless. Nobody offered to help me. I felt abandoned and resentful. Then I realized that I could find out the information I needed by looking at my program packet, or at the signage in the building, or by asking other people where they were going. I discovered that I don't have to be anxious and helpless when I don't know what's going on. I don't have to wait for someone else to come along and rescue me. I can figure out what information I need, and empower myself to go out and get the information for myself.

or

I wasn't sure what to do or where to go or what was expected, and [nobody offered to help me] [people did things that they said were 'help' but I did not find helpful]. I realized that Autreat is not a comfortable experience for me. I am empowering myself by deciding [not to attend Autreat again] [to make my own arrangements to have a helper with me if I attend Autreat again].

or

I wasn't sure what to do or what was expected, and nobody told me what I should be doing. I felt very lost and disconnected. Without external cues telling me what I should do and be, I started feeling as if I didn't exist at all. I realized that I've built so much of my life around trying to be what other people expect me to be that I don't actually know who I am, or even if I am, apart from other people's expectations.

(The latter is an experience that I call "explosive decompression," and fortunately it doesn't happen very often. I've seen it happen to three or four people over the 20 years since I started seeking out other autistic people. It's very terrifying while it's happening. But it is survivable, and can be the first step toward discovering that one does exist independently of other people's perceptions and expectations.)

While it's more common for people to either appreciate or be bothered by a lack of spontaneous interaction in autistic space, some autistic people do initiate a lot of spontaneous interaction. Even when we initiate, we still don't tend to engage in NT-style small talk. We just start talking about whatever subject we happen to be interested in at the time.

When this happens in NT social contexts, instead of complaining about failure to initiate, NTs complain that autistics are approaching people inappropriately and are talking about odd or uninteresting things. In autistic social space, people are less likely to be put off by non-standard conversational topics. Personally, I would much rather have someone walk up to me and tell me some interesting fact I hadn't known before about grasshoppers, or helicopters, or forensic dentistry, than have someone approach me uninvited to tell me something I'm perfectly aware of, such as the fact that it's a sunny or a rainy day. If you're going to interrupt my train of thought and place demands on my cognitive processing to focus on you and comprehend what you're saying, at least say something that's intellectually engaging!

But for someone who is already struggling to remain oriented among unfamiliar people in an unfamiliar environment, any unexpected interaction at all, any disruption of a planned course through space and time, can be experienced as unwelcome and intrusive. And autistic people are not perfect; sometimes we do things that really are intrusive (i.e., that interfere with other people's ability to exercise their legitimate rights and freedoms), not merely unusual.

Given the great variability among the autistic population, both in what we want and in how we express ourselves, we can't expect to be able to interpret each other's cues or to guess each other's wishes. In autistic social space each person is responsible for explicitly communicating his or her wishes regarding interaction.

It's acceptable to choose not to interact. It's acceptable to choose to interact only with some people, or only at some times, and not with other people or at other times. It's acceptable to talk about things you're interested in. It's acceptable to tell someone else to stop talking to you. It's acceptable to approach people who differ from you in age, gender, race, ethnicity, education, income level, or other indices of social status.

It's acceptable, and expected, to say what you mean. It's not acceptable to expect people to figure out what you need, what you want, or what you mean, if you don't explicitly say it. And it is very unacceptable to try to tell other people what they need, want, feel, think, or intend. (NT readers, please take special note of this point of autistic etiquette: NTs seem to consider it an expression of "empathy" to label each other's wishes and feelings. Autistic people are not likely to appreciate being told how [you think] we feel. And if we don't take the initiative to label your feelings for you, that doesn't mean we don't care how you're feeling. It only means we don't presume to know how you're feeling, unless you tell us.)

In autistic space, communication is the responsibility of the individual, not the group.

Receiving and Giving Assistance

Many autistic people's social experiences have involved "all or nothing" dynamics: Either we are expected to function normally without needing or requesting any accommodations or assistance at all (Smith, 2005); or else we are led to expect that we are invariably less capable than everyone else around us, and that other people in general are more flexible than we are, available to assist us when we need help, and willing to adjust their behavior to accommodate our needs (Van der Klift ,1994; Lane, 1992; Shapiro ,1991).

In autistic space, most of the people around us are themselves autistic. While it would be possible for a group of autistic people to hire support staff for an autistic event, and the staff would then work under the direction of autistic people, I have never seen this done in practice. In the shared autistic spaces that I am familiar with, there are neither designated official caregivers for autistic participants, nor is there a majority of nondisabled fellow participants.

In the absence of both official support staff and a surrounding nondisabled majority, autistic people in autistic space can have the opportunity to try doing things for ourselves. We may be awkward; we may be inefficient; we may fail initially and have to try again; we may eventually give up and ask for help. But we have a chance to try, without having uninvited "helpers" zoom in to tell us we're incapable and to relieve us of the opportunity to explore our capabilities. As a result, many autistic people discover in autistic space that we really are capable of doing things we'd never known we could do.

In autistic space it's also possible that someone who is accustomed to always being the one in need of help (or at least to always being perceived that way) ends up being able to provide help to a peer. One autistic person reported that this was such a powerful experience, she had to restrain herself from thanking another participant for having a problem and allowing her to feel good about being able to help.

For the person receiving the help, it can make a big difference whether the assistance comes from an autistic peer or from an NT. Being helped by an autistic peer allows one to see an autistic person in a position of strength and competence. Even if one is not feeling particularly strong or competent oneself at the moment, one is reminded that autistic people can be strong and competent. Peer assistance also presents the possibility of reciprocity and mutual support, rather than one category of people always being dependent and another category of people always being depended on.

The dynamic of peer assistance can change the attitudes and perceptions of NTs as well as of autistics. At one autistic event I observed an autistic person sitting on the floor in a hallway, sobbing. I did not immediately assume that she wanted to be interfered with, but following a brief assessment of the situation, I approached her and asked if I could help her. As we sat there conferring, some other autistic people saw what was happening, and sat on the floor with us and talked. One person walked by without saying a word and handed the crying person a visual stim toy. That gave me the idea of getting my MP3 player and playing a particular song for her. Eventually there were four or five people (as well as a stim toy and an MP3 player and a pair of speakers) sitting on the floor trying to help the person who was upset, and meanwhile blocking the hallway. An NT professional came by. As the professional picked her way carefully through all of us sitting on the floor, she remarked, "You're certainly giving the lie to everyone who says autistic people don't have empathy." Then she went on her way, leaving us to deal with our own distressed peer, clearly recognizing that we did not need her to come to the rescue.

While such instances of autistic peer support can be extremely powerful and meaningful both for the people receiving the help and the people providing it, autistic peers cannot be expected to have the same "helping" mindset that many of us have grown accustomed to in our dealings with NTs. Nondisabled people in general, and habitual caregivers in particular, often perceive any disabled person as being in need of their assistance. They swoop in to "help" regardless of whether or not the disabled person has asked for any help. (This can reinforce a disabled person's sense of helplessness and dependence, and interfere with learning to do things independently.)

In contrast, autistic people who gather to celebrate autistic togetherness often aren't inclined to perceive either ourselves or our peers as helpless, powerless people. Even acknowledging that we have significant disabilities and require more support than nondisabled people, most of us expect ourselves and our peers to be capable of managing our own support needs.

If it should happen that someone isn't able to manage, we may or may not recognize that the person needs help. Autistic differences in nonverbal communication mean the person who needs help may not be generating recognizable signals of urgency, and bystanders may not pick up on such signals even if they were present.

If we do notice that someone needs help, we may not know how to help. The variability among autistic people means none of us can assume that another autistic person needs the same things we would need in a similar situation.

Even if we can tell that someone needs help and the person can explain just what manner of help is needed, we may be strained to near our limits just taking care of ourselves. We may not have the spare energy to help someone else. Most NT people, in familiar NT social settings, are at a manageable level of stimulation and energy expenditure. Autistic people, for reasons discussed previously, may be struggling to cope even in an autistic environment, and may simply not have the processing capacity to take on another person's problems.

| Overstimulated and stressed |  |

|

| Comfort zone |  |

|

| Understimulated and bored |  |

Being among people who don't rush to offer assistance at the first sign of difficulty, and may not be able to help even if asked, can be a severe shock to people who are accustomed to being able to turn for help to whomever happens to be nearby when they need help. A few people at Autreat have expressed the feeling that no one cared about them and no one was concerned about what happened to them, because no one gave them the kind of help they wanted or needed. The fact is that autistic people are no less likely than NTs to care about other people and to be concerned about what happens to them. We just may not be in a condition to be able to take care of another person, in a situation where we're not familiar with the other person and his/her needs, and had not expected or prepared to be in a caregiving role.

If someone in an autistic social environment is having an obvious emergency, such as a severe injury or illness, other people will most likely notice and try to help. We may not be able to provide any help beyond calling for an ambulance or police, but at least we can do that much. But for less dramatic difficulties and support needs, such as needing help with personal care, orientation and navigation, time management, making choices, or coping with emotions, one cannot always expect other autistic people to be able to drop whatever they're doing in order to help. Other autistic people are likely to be struggling to keep up with our own self-care and to maintain our own physical, cognitive, and emotional equilibrium. We may not know a solution to whatever problem another person is having. We may be having the same problem ourselves, or we may be having different, but equally difficult, problems. We may simply not be equipped to assist another person, when we're already using all our energy taking care of ourselves.

Some autistic groups exclude people who need personal assistance and support, in order to prevent situations in which someone needs more assistance than other group members can provide. Within ANI and at Autreat we do not exclude people based on needing a lot of personal help. Instead we advise people that if there's any kind of help they need badly enough that it would be a serious problem if no one is able to provide that help, they should make their own arrangements to have a support person who can help them.

In autistic space common autistic needs are understood, and to some extent are predicted and accommodated by the structure of our activities and events. To the extent that different people need different, individualized accommodations, people are welcome to communicate their needs. More, they are expected to take responsibility both for communicating their needs, and for participating in working out strategies for getting their needs met (Autism Network International, n.d. b; Autscape, 2009). This is an opportunity for people to reframe their experience of "needing help" from one of helplessness and dependence to one of dignity, autonomy, and equality with fellow participants.

For people who have never been "allowed" to acknowledge autistic difficulties or to ask for support, this freedom, even encouragement, to express needs and request accommodations can present surprising and previously unimagined possibilities. People may begin to envision, and consider, and experiment with, doing things they'd never thought they could possibly do, or would ever want to do. Trying new things opens opportunities to experience new successes — and also opportunities to experience new failures and frustrations. Often people don't even know what kind of assistance and accommodations would help them. Finding out what works is a process of trial and error, disappointment and discovery.

Logistics of Autistic Space

Contact a la Carte

When preparing any kind of offering for autistic people, organizers are presented with the challenge of accommodating the tremendous diversity among autistics. Creating something that everyone likes and everyone finds easy to participate in is an impossible goal. Instead, our approach within ANI tends toward offering a variety of different options, allowing individual participants to pick and choose which ones they want and opt out of the ones they don't want.

This didn't require much organizer attention or planning when we had limited options to choose from, and those options involved minimal interactivity. When all we had was a newsletter and a penpal list, the options were very simple: subscribe or don't subscribe to the newsletter; be listed on the penpal list or don't be listed. People who contacted each other privately through the penpal list were able to negotiate their own contacts without any involvement by group organizers.

Our online forum created much more opportunity for contact and interaction between members. This opened the way for more conflict between the needs and desires of different members. Some autistic people wanted a forum for autistic people only, with no NTs allowed. Some parents wanted to hear from autistic people and from like-minded parents about autism-positive approaches to raising and educating their children, but weren't interested in having their inboxes flooded with large numbers of messages about square-dancing llamas or whatever other fun subject autistic members might start perseverating about. Some autistic people were interested primarily in peer social contact and emotional support. Some were interested primarily in disability rights and political advocacy. Some people (autistics and parents alike) found it emotionally traumatizing to read activist posts containing upsetting accounts of mistreatment of autistic people.

We were able to use an existing feature of the listserv environment to enable individual members to choose the types of posts they did and did not want to receive. The "Topics" feature of the listserv software allowed us to subdivide the forum into various sections, and allowed each member to opt into some sections and opt out of others. The Topics feature was probably designed originally to be used on professional mailing lists, dividing discussions according to technical specialty. But we implemented it for a social purpose, to allow our members to personally customize the kinds of sharing they were interested in: peer discussion among autistics and "cousins" (Cousins, 1993; Shelly, 2003), discussion of interest to parents and professionals about meeting the needs of their children or students or clients, disability rights and politics, and eventually also a virtual party section for times when a lot of fun posts were being sent in near-realtime interaction, and a conference section for list members who planned to attend conferences or other live events and wanted to make plans for meeting each other at those events.

The listowners had to do some extra work to implement the Topics feature so that members could have this degree of individual choice. First we had to learn how to use the feature ourselves. Then we had to teach group members how to use it. There was some initial anxiety and resentment among members over having a new complication introduced to their use of the forum, some people who were certain they'd never learn to get it right, and some people who went overboard criticizing other people's mistakes. A lot of people were intimidated by the instructions for setting up their own Topics options, and the listowners received many requests for individual coaching and assistance.

For the most part, after a brief adjustment period, people caught on and recognized both the logic and the usefulness of the feature. People became more confident and less anxious with practice. People became less critical and more supportive when other people made mistakes. Experienced list members cheerfully helped newcomers learn the ropes. As the Topics feature became incorporated into ANI-L culture (complete with virtual M&Ms for reinforcement) there was more peer instruction and support, and less reliance on listowners to provide individual assistance.

When we took the step from online contact to physical gatherings, there were even more opportunities for interaction, more intensity and immediacy of interaction, and greater diversity among participants. Participation in written exchanges, whether in print or online, requires the ability to use language. People who cannot read, write, or speak can and do attend live gatherings.

Organizing autistic physical spaces requires attention to participants' orientation and sensory needs, because people are leaving their own familiar personal spaces and coming into a new shared space. It requires the creation of structure for people to maintain their own personal boundaries and recognize other people's boundaries. It requires a great deal of detailed pre-planning by organizers, so that autistic participants are not overwhelmed by the need to attend to too many details on their own.

A central dilemma of autistic togetherness is that on one hand, most autistic people are easily overwhelmed by having to make complex social arrangements, such as needing to organize their own travel and hotel reservations and meals and personal leisure time and informal social plans with other participants and local transportation between conference facility, hotel they're staying at, hotel their desired social contacts are staying at, restaurants, recreational facilities, and whatever else they need or want while attending an event away from home. The retreat structure, in which formal activities (presentations and workshops), informal social and recreational opportunities, meals, and lodging are all available within the same venue, simplifies things immensely for the participants. Often this can make the difference between an autistic person's being able to attend at all vs. being unable to handle the complexity of making all the detailed arrangements. On the other hand, the variability among autistic people means that we require careful individualization of our arrangements, and accommodation of a great variety of different and sometimes conflicting special needs. The concept of "one size fits all" does not work in autistic space!

Autistic gatherings such as Autreat, and other events I'm aware of that have adopted a similar model, balance this tension the same way we accommodate autistic differences online: by providing a variety of different options and allowing people to make their own personal choices. Autreat offers a selection of presentations on topics we know to be of interest to many autistic people. No one is required to attend any of those presentations, and if someone does attend one and finds it uninteresting, it's perfectly acceptable to get up and leave. We offer informal group discussions and recreational activities. No one is obliged to attend any of these, and if someone chooses not to join in, Autreat social rules specifically proscribe pressuring people to participate. There's a pool where people can swim, and posted hours when it's open for swimming, but no herding of participants to the pool for swim times. The general principle is to provide opportunity but not pressure.

Autreat has always been organized as a residential retreat with on-site meals and lodging, partly to minimize costs to participants, but mostly to minimize complexity for people who prefer not to have to attend to each and every detail for themselves. People can register for the "standard" Autreat package which includes meals and lodging, and then once they manage to get themselves to the venue, they can eat, sleep, socialize, participate in formal and informal activities, and take down time when they need it, all without needing to travel off-site or decide all the minute details of their daily routine. But if some aspect of the standard package doesn't meet their needs, they can opt out of that part of the package and make their own personal arrangements. If they prefer the greater privacy and comfort of a hotel room to the shared lodging on-site, they can register for day attendance only, without overnight lodging. If they prefer the 24-hour immersive experience of lodging on-site but don't want to share a room with another participant, they can request a private room for an additional fee. If the Autreat meal plan doesn't appeal to them, they can register without paying for the meal plan, and make their own arrangements to bring food with them or go to restaurants near the venue. If they're not up for attending the full retreat (currently lasting four days and four nights), they can register for as many days as they wish to attend.

This degree of individual choice and program adjustability is not built into the standard event-hosting services offered by most conference or retreat venues. In seeking suitable venues for an autistic gathering, the organizers need to negotiate exacting details that the venue staff are probably not accustomed to having to think about. Each time we've searched for a new venue for Autreat (our current venue is the fourth), our checklist of requirements has included such things as allowing participants to opt out of the meal plan and/or on-site lodging, having facilities available for participants to store their own personal food, providing menu information well in advance of the event so people can decide whether or not to sign up for the meal plan, providing complete lists of ingredients for each dish so people with food allergies can find out what they can safely eat (the latter two requirements are constant sources of frustration when venue staff don't realize how important they truly are), having some "modular" food choices such as salad and pasta and sandwich bars for people who have trouble eating "mixed together" foods, and allowing people to take their trays out of the dining hall and eat in their rooms if the dining hall is too noisy and crowded for them.

Information and Orientation

As ANI space has developed from a small group of friends visiting each other's homes, to a larger group of email correspondents in our own online forum, to a four-day retreat where dozens of people share physical space, our approach to the challenge of unfamiliarity has been to provide a lot of detailed information to help people get oriented. Early home visits were typically preceded by email exchanges or (less frequently) phone calls in which people planned the visits and asked each other questions about what to expect in being together. The ANI-L forum has a set of rules and policies that people are required to read before they are allowed to join the forum. People who register for Autreat are sent a collection of files before they attend, providing extensive details about the venue, daily schedule, and Autreat customs and social expectations. There is an Autreat Information forum online where people can ask questions and share information and pre-plan their Autreat experience. There is an orientation session on the first evening of Autreat where non-readers can hear the information that was sent in advance to read, and everyone has a chance to ask questions.

Most autistic people who are capable of formulating questions have frequently experienced the following scenario: We ask for information that we need in order to prepare ourselves for a new experience. Instead of answering our questions, NT people tell us that we don't need to ask these questions at all. We just need to relax and stop being so anxious. The fact is that being able to ask questions, and getting clear answers to our questions, and thus knowing what to expect, are often the very things autistic people need in order to be able to relax and not be anxious. Asking a lot of questions about the details of a situation is usually not a "maladaptive behavior" that increases an autistic person's anxiety. More often it's an adaptive strategy that an autistic person is using to reduce anxiety or to prevent being in an anxiety-provoking situation in the first place. It's very important for us to have thorough explanations and ample opportunities to ask questions.

Experience has taught the leaders of ANI and Autreat that taking time to answer people's questions is a necessary part of organizing autistic activities. And for autistic people who participate in these activities, learning to identify the information they need, and to ask the right questions to enable their participation, is an important self-advocacy skill.

Autistic Social Rules

Autistic people commonly have difficulty with NT social rules for three basic reasons: We may not know what the social rules are; we may know what the rules are but not see any reason to comply with them; or even if we would like to comply with the rules, the demands of social compliance may be inimical to our natural ways of processing.

Autistic social rules develop and evolve naturalistically within autistic space, just as social rules and customs develop naturalistically within any other community. Autistic rules and customs reflect common characteristics of autistic people.

Autistic people characteristically do not pick up on vaguely described, implied, or unspoken behavioral expectations. We don't often learn by "social osmosis." Therefore, in autistic space the rules and the expectations are clearly and explicitly spelled out, sometimes in excruciating detail.

Besides being explicitly spelled out, autistic social rules are also clearly explained. Some autistic people scrupulously, even rigidly, follow rules simply because they've been told that they're rules. Other autistic people care nothing at all for rules unless the rules make sense to them. At both extremes of the rule-following spectrum, as well as for autistic people in between, it is helpful to have clear explanations of the reasons for rules. If we know why something is a rule, and we can understand that the rule makes sense, then those of us who require logical explanations are more likely to respect and follow the rule, while those of us who tend toward rigid rule-following are better able to be flexible when necessary. In autistic space, asking "Why?" is a perfectly normal and acceptable response to a rule, and is not considered impudent or disrespectful. Autistic community leaders who create rules must be prepared to explain and justify those rules.

Most autistic people who have never experienced autistic space have never meaningfully experienced "social rules." And until there was such a thing as autistic space, there were no such things as autistic social rules. But once autistic space came to be, autistic people began doing kinds of social processing that we had never done before. As a result of this authentic autistic social processing, authentic autistic social rules began to emerge. Autistic social rules evolved in accordance with autistic processing, and meanwhile autistic social processing was able to further develop because of the facilitative environment created by the autistic social rules. Thus, autistic social rules develop synergistically with autistic processing both online and in real space:

The ANI-L forum was created in the aftermath of heated conflict between autistic adults and NT parents in an NT-dominated autism forum. Some early autistic members were reluctant to allow NT parents to participate, and some early NT members were apprehensive about whether their participation was welcome and appropriate. The social rules we created involved detailed and extensive written rules for the forum; the division of the forum into different sections for discussion topics of interest primarily to autistic people and discussion topics about parenting; firm boundaries defining what kinds of topics could be discussed in which section; and clear identifying signals (using the Topics feature) enabling people to recognize what kind of message to expect before opening a post.

Autistic processing — explicit statements of the group's rules, very detailed explanations of the reasons for those rules, clear boundaries to maximize individuals' ability to pick and choose among available options for contact, and protection of autistic people from adverse forms of contact — produced those rules. NT communities probably would not make such rules.

The autistic rules enabled autistics to have experiences that we couldn't have anywhere else: the development of social connections with autistic peers, and also with NTs who were willing to respect our rules.

These new experiences and connections led to greater familiarity and comfort with social interactions in autistic space, more spontaneity, less "us vs. them" thinking between autistics and NTs, and less rigid reliance on constantly checking the rules.

The original rules may be seen as creating separation and distance between autistics and NTs. From our perspective, what we were doing was acknowledging differences between autistics and NTs — as well as between autistics and other autistics — and claiming the forum as autistic space where autistic needs and autistic sensibilities have priority. Through acknowledging our differences, claiming our own space, and accommodating autistic processing needs (e.g., clear and detailed rules), we were able to have the experience of successful and enjoyable interactions between autistics and NTs in a comfortable autistic space. These successful interactions created bridges to traverse the original distance between us. Within a year of its creation, the ANI-L forum had evolved into an integrated community of autistic and NT people sharing ideas as equals.

A similar pattern unfolded with gatherings in physical space. Before the ANI strand in the 1995 parent-oriented conference, ANI members used the ANI-L forum to discuss what we needed to make the physical space comfortable and safe for us. Our online forum provided a safe and comfortable virtual space in which we could discuss our past experiences with, worries about, and possible solutions for live gatherings. Among the things we came up with was a set of "Guidelines for Interacting with Autistic Speakers and Attendees" based on experiences many of us had had at other conferences. These guidelines stated clear and firm boundaries regarding contact. They explained the reasons we need these boundaries.

We were told by one of the NT conference organizers that our interaction rules would be perceived as rude and unfriendly by NT conference participants. We insisted that they were necessary anyway.

That conference was attended by a larger group of ANI members than had ever come together in real space before. With our social rules clearly stated and explained, most of us were able to have a wonderful experience of autistic togetherness — and also have some positive real-space encounters with NTs who respected our processing needs and accepted our rules.

Those same guidelines, with only minor modifications, remain in place as Autreat rules. For thirteen years, as of this writing, dozens of autistic and NT people have been able to come together each year with remarkably few serious difficulties, and share a great many positive experiences ranging from simple "fun times" to profoundly life-changing insights and discoveries.

Autreat social rules and customs, which have been adopted by some other autistic-run events around the world, include:

- Accommodation of other people's sensory sensitivities. Flash photography, use of perfumes or scented personal care products, and touching people without permission are all prohibited by Autreat rules. Smoking is limited to designated smoking areas, and if people come to group activities smelling of smoke, they may be asked to go change their clothes. Loud activities, such as music and dance sessions, are assigned to places in the venue that can easily be avoided by people with auditory sensitivities.

- Respect for people's privacy. We do not compile an Autreat participants' directory in advance. People make their own individual decisions about what personal contact information they wish to give out to which fellow participants. We have an Autreat privacy agreement which everyone is required to read and sign. We have an even more restrictive set of rules for journalists or researchers who wish to gather material at Autreat for research or publication.

- Use of badges as visual cues. Many autistic people have difficulty recognizing faces. We therefore strongly encourage Autreat participants to wear their name badges at all times when they're in group space (except in the pool) so other participants can recognize them. People who don't wish to be photographed at all, even under the terms specified in the privacy agreement, may wear a black circle badge ("photon trap") to signal that they are not to be photographed. Since many autistic people do not generate automatic nonverbal signals to indicate their interaction-readiness, nor pick up on such signals from other people, we provide optional color-coded interaction signal badges. People can use these badges to indicate whether they wish to be left alone, are open to interaction with familiar people but not with strangers, or are having trouble initiating interaction and would like someone else to approach them and initiate.

- Respect for boundaries. Autreat social rules don't require "acting normal" or suppressing "weird" behavior. Actions are determined to be acceptable or unacceptable based on whether or not they infringe on other people's boundaries (Sinclair, 2004). As coordinator, whenever I have occasion to mediate a conflict among Autreat participants, I generally start by identifying and clarifying the relevant personal or group boundaries. I almost always find that once the situation is framed in that manner, people are able to arrive at reasonable and mutually acceptable conclusions.

At Autreat as on ANI-L, we have accommodated autistic processing by providing clear and detailed rules, logical explanations, careful attention to boundaries, and individual freedom to choose among available options. At Autreat as on ANI-L, these accommodations have created a social environment in which autistic people have been able to have social experiences that we don't have anywhere else.

I realized this for myself just before the first Autreat in 1996. While our current venue offers apartment-style lodging with only two people per room, our first venue was a camp facility in which six or more people shared each cabin. The camp administrator had told me that there were two private rooms in the infirmary building, and that when groups rented the facility for retreats, the group leaders usually stayed in these private rooms. I decided it was more important to make those private rooms available for people who needed them for accessibility reasons. I made all the cabin assignments based on participants' completed questionnaires, then called the camp administrator to read her the names of the people who would stay in each cabin. When I read my own name on the list assigned to a cabin, the administrator said, "I thought you were sleeping in the infirmary." Without even thinking about it I said, "No, I'm sleeping with my friends." I was startled and then astonished to hear myself say such a thing. I realized that I would rather share a cabin with my friends than have a room to myself. I realized that I actually had friends — five of them! — whose company was so enjoyable to me that I'd willingly give up the luxury of a private room in order to spend more time with them. This is not something I would ever have imagined myself choosing, before I had any experience of autistic social space.

I've observed many similar examples of autistic people doing things at autistic gatherings that are contrary to conventional observations of autistic social behavior. During the first few years of Autreat we planned few or no group activities other than workshops. The very idea of "group social activities" was too threatening to people whose past experience of social activities had involved coercion, rejection, failure, or other sorts of unpleasantness. Gradually as people grew more secure in the acceptance of peers and the freedom to opt out of activities in autistic space, it became less scary to consider deciding to opt in. We also discovered that there were more interesting possible activities to opt into, in a group of people who shared similar interests and processing styles.

Autreat rules are carefully designed to protect people from unwanted social and sensory intrusions. People are expressly told not to touch anyone in any manner at all without permission. People who don't want to be touched can be secure in the knowledge that nobody is likely to touch them (and that if anyone does touch them, they're allowed to protest). With the freedom to consciously choose whether and when and how they want to be touched, some Autreat participants have recently been discussing possible adaptations of the badge system to signal that they are open to hugs.

The Autreat dining room may be the quintessential example of this phenomenon. It's a common stereotype that autistic people in a group dining situation sit alone, as far away from other people as possible. And indeed there are people who choose to sit alone in the Autreat dining room, or to take their meals out of the dining room to someplace more private. We expected that from the beginning. We negotiated agreements with all our venues to accommodate the needs of people who opt to eat alone.

But there are also people at Autreat who not only choose to sit together, but who actually crowd closer together in order to fit more people around a table than the table was designed for. I have watched an autistic person bring a tray from the serving area, walk to an empty table, take a chair from that empty table, and carry it to another table where all the chairs were already occupied. I've seen the people already at that table move closer together to make room. I've seen this happen again and again with person after person, until as many as ten people — most or all of them autistic — are happily crammed around a table that was meant to seat six.

The Future

Our community is still young, but a generation of autistic children has already grown up having experience and familiarity with autistic togetherness. We're a small minority among an NT majority, but more and more of us are reaching out, finding each other, and making connections. Twenty years ago it was almost impossible for an autistic adult make to contact with even one other autistic person (unless that autistic adult was one of the fortunate autistic people who have autistic family members). Today there are numerous autistic forums and web sites and blogs on the Internet, autistic social and support groups in many cities across the U.S. and around the world, and immersive cultural experiences in several different countries. Autistic children today have the opportunity to grow up with knowledge of themselves as autistic people, with awareness of possibilities and resources for them to lead happy and meaningful autistic lives.

We face many serious challenges, as individuals and as a group. But now, for the first time, we are able to face them together.

Appendix: Personal Logistics in Autistic Space

For readers who have never experienced autistic space but think they might like to, I offer the following tips:

Know yourself. Carefully consider your own personal characteristics, your strengths and abilities, your weak points and support needs, your likes and dislikes, and what you hope to get out of your experience with autistic space.

Carefully review information about the activity or event you're considering participating in. Is it a good match with your interests? Is it offering something you're likely to enjoy?

What will you need to be able to do, in order to participate? Will you need any kind of individual support or assistance to be able to do these things? How can you arrange to have that help available?

If you're considering traveling to a live gathering such as Autreat, don't forget to consider your travel needs too. You won't have a very good time at the event if you have a disastrous travel experience before you get there.