In the post-socialist region, both disability NGOs and disability research have been hostages of the medical model. The last decades mark the end of this dependence, however, a question remains over whether disability activism and research have become allies, implementing human rights-based disability policy. The goal of this paper is to reveal the relationship between academic disability research and disability activism and their influence on disability policy in the post-socialist region. The objectives of the research are to analyze the peculiarities of academic disability discourse and disability activism, their intersection points as well as their actual impact on disability policy. As a reference point for this analysis, we will take the trends of disability discourse and the rise of disability activism in the Global North countries. Thus, this paper contributes to the „careful dialogue" (Rassel, Iarskaia-Smirnova, 2013) between the post-socialist and Western understandings of disability. Authors overview the emergence of civil society and disability activism in post-socialist countries, discuss the changing role of researchers in the disability field, present and compare findings from experts' research, and quantitative content analysis of disability-related academic texts.

Introduction

The UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (2006, hereafter CRPD) is the result of disability activism and embeds principles of non-discrimination and inclusiveness. Nevertheless, a long road had to be traveled until an international discourse culminated in the CRPD. The disability paradigm change started and accelerated with the development of disability activism in the 1960s, which meant a global social movement to secure equal opportunities and equal rights for all people with disabilities (hereafter PWD) (Barnes & Mercer, 2006). These movements united PWD, championed their rights, and questioned outdated practices:

From a civil rights perspective, a profound and historic shift in disability policy occurred in the 1970s. Following the powerful civil rights activism of the 1960s, the 1970s produced a more fundamental change in the social and legal status of disabled people than any prior era of American history (Mayerson, 1989, pp.2-3).

Historically, disability activism facilitated the establishment of disability organizations, national and international disability networks. E.g., such as the Union of Physically Impaired Against Segregation (UPIAS) which had been formed in the United Kingdom after disability activist Paul Hunt, a "former resident of the Lee Court Cheshire Home wrote to the Guardian newspaper in 1971, proposing the creation of a consumer group of disabled residents of institutions" (Davis, 2016, p. 196). UPIAS is famous for developing the concept of the social model of disability in 1975 which was introduced into the academic discourse in 1983 by Mike Oliver who had a disability himself. Disability activism also predisposed the path of disability research. Under its influence, new fields of research emerged, such as rights of PWD, inclusion, implementation of the CRPD, and many others. Disability research is increasingly being implemented under the leadership of scientists with disabilities.

In the post-socialist region 1 for over half of the 20th century, both disability NGOs and science were hostages of the medical disability model. This was caused by an ideology of marginalization which was one of the essential features of the political system. In the 20th century, the science of defectology 2 provided academic justification for residential care in the Soviet Union and other socialist bloc countries. As a normative approach, it neglected social aspects of disability focusing on its clinical issues both in research and in practice (Rasell, Iarskaia-Smirnova, 2013). The political and public discourse claimed that isolation of people with disabilities was required both for their own and society's safety and security. Such a disability policy turned the socialist bloc countries into a region with highly institutionalized mental health services.

Disability movements in the post-socialist region started together with the rebirth of civil society in the early 1990s. These movements quickly developed into national non-governmental umbrella organizations. The post-socialist countries did vary in terms of their political-cultural and educational structures and practices, which also has ramifications for how disability activists, organizations, researchers act in the disability field. But advocacy for disability rights, inclusion, and community care services were the main subject of their activities. Hence, the disability activism in the post-socialist area echoed the Western direction but in a more dynamic way: diverse disability initiatives rapidly emerged, developed, expanded, and in many cases these periods and types overlapped with each other. Were these movements backed by the academic discourse and in what ways? This is one of the issues we will further analyze in our article.

This paper aims to investigate the relation between academic disability research and disability activism in the post-socialist area and their influence on disability policy. The approach to disability in post socialists countries cannot be reduced to their socialist past and is not monolithic, distinctive combination of economic challenges, social changes, and access to international influences that characterize post-socialism (Rasell, Iarskaia-Smirnova, 2013; Sumskiene, Gevogianiene, Geniene, 2019). The experiences of disability are highly contextual and contingent (Rasell, Iarskaia-Smirnova, 2013), therefore the above mentioned elements create a broad framework for the analysis of the general trends of disability activism and research in these countries. We will take the trends of disability discourse and the rise of disability activism in the Global North countries which have served as a reference point for the countries liberating themselves from the communist past (Stark & Bruszt, 1998). Despite the common difficulties which people with disabilities face throughout the world (social stigma, inaccessibility of the built environment, etc., Rasell & Iarskaia-Smirnova, 2014) there are also worldwide discourses on human rights that cross the borders of political regimes. To our understanding, CRPD is the culmination of the discourse on the rights of people with disabilities and therefore we take it as a platform for the analysis of the change in disability awareness, research, and practice.

Research questions were as follows: what are the specifics of the academic disability discourse and disability activism? Do they follow the same disability paradigm, adhere to the same values? Do they supplement or contradict each other while affecting disability policy? Which of them dominates, overrides, or ignores the other? Are there similarities and/or differences in the paths that post-socialist countries follow compared with the development paths in the Global North? 3

To answer these questions, we first overview the emergence of disability activism and discuss the changing role of researchers in the disability field. To understand the relation between the level of development of civil society and organizations both of and for persons with disabilities (further – disability organizations) and the role of academic research we describe the peculiarities of post-socialist societies and, finally, present findings from the experts' research and quantitative content analysis of academic texts.

The emergence of disability activism

Hundreds of people arrived at the planned protest march in San Francisco on April 5, 1977, weighed down by backpacks bulging with food, medication, and basic supplies… The crowd was largely comprised of individuals who were deaf, blind, using wheelchairs, living with mental disabilities, and living with paraplegia and quadriplegia. (Shoot, 2017, para.1).

That was the beginning of the longest non-violent occupation of a U.S. federal building in history, initiated by disability activists. Half a century later, disability activism continues and spreads through the globe, including the post-socialist region. F.i., The Polish Protest for the Rights of People with Disabilities in 2018 was led by Polish activists with disabilities in response to the inadequate treatment of persons with disabilities by the Polish government. On the 30th of July 2018 over a thousand people took to the streets of Sofia to protest against the inadequate political reaction to the demands of mothers of children with disabilities. The march took place under the slogan "The System is Killing Us – All" and is part of a months-long campaign for a better, more personalized social support system for people with disabilities and their families (Dimitrov, 2018). Such protests are aimed at fostering public discourse, challenging exclusion-oriented policies, financial cuts, and public ignorance. Similar to other social movements, disability activism emerged as an answer to oppression and injustice, experienced by PWD. This activism had two main directions: firstly, to empower PWD to take control of their own lives; and, secondly, to influence social policies and practices of inclusion (Winter, 2003).

From its beginning, disability activism has evolved through three phases, as identified by disability and social movements' researchers (Spector & Kitsuse, 1977 (see in Blanck, 2004); Winter, 2003; Blanck, 2004). Two of these phases (the first and the last one) distinguish themselves by an immense shift of relations between science and disability activism. The first phase consisted of the definition of the problem and identification of its sources "in the dominant ideas and practices, the hegemonic plausibility structure, which constitute the medical model of disability" (Winter, 2003). At this stage, disability activism had a tense relationship with the predominant treatment-oriented academic disability discourse and strived for emancipation. The second phase included intense endeavors to find legitimate legal solutions, the involvement of disability organizations (as a manifestation of civil society), and an ideological shift towards independence (Winter, 2003; Blanck, 2004). During the third phase disability activism faces new challenges, such as the need to reform systems of health care, education, cooperation with business, and authorities (Winter, 2003; Blanck, 2004). This stage marks the re-negotiation of relations between disability activism and science, finding allies among scientists, and applying evidence-based argumentation for their cause. In the following section, we'll discuss the role of researchers in promoting advanced approaches to disability.

The position of disability research

Links between the academic community and disability activism historically have not been straightforward. Development of scientific medicine at the beginning of the 20th century granted physicians knowledge and authority: (Devlieger, 2003, p. 99). The medical model claimed to be scientific, at the same time it was considerably ambivalent toward the people it professed to aid and institutionalized expression of societal anxieties about PWD (Longmore, 1995).

Like every social movement, the Disability Rights Movement needed critical analysis of the social problems it was addressing. This need enhanced the development of their own scholars who often represented the community of persons with disabilities and also worked in academic institutions (Longmore, 1995). Their research widened the disability perspective and contributed to the gradual evolvement of disability studies, which gained a permanent platform in academic literature since 1990 (Priestley, Waddington & Bessozi, 2010). Disability studies have been conceived as a bridge (or a metaphoric ramp – Longmore, 1995) – between the academy and the disability community. The emerging disability activism was accompanied by a steady growth of interest in disability amongst social scientists, also in the post-socialist region (Jonas Ruskus (currently working in the UN Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities of the UN), Dainius Puras, Darja Zavirshek, Teodor Mladenov, Elena Yarskaya – Smirnova, Ines Bulic, Sarah D. Phillips and many others). Yet, post-socialist disability studies are rarely institutionalized as a specific discipline, and they often fold into the disciplines of social work, social policy, or sociology (Philips, 2011, cited in Rasell & Iarskaia-Smirnova, 2013).

For a long time, scientists were focused on communicating scientific knowledge to society, and less attention was paid to a reverse process – involving members of society who were "researched" to design the research agendas themselves (Danieli & Woodhams, 2005; Priestley et al., 2010). Gradually, the development of critical disability studies has led to the "emancipatory" paradigm of disability research which implies a stronger influence of disability organizations on the research agenda (Danieli & Woodhams, 2005; Priestley et al., 2010). However, researchers quite selectively interpreted the emancipatory paradigm, and there is still a lack of systematic efforts to cooperate with disability organizations by giving them a priority to set strategic research aims (Priestley et al., 2010; Rosner, 2015).

Consequently, disability activists argue that researchers lack competence in human rights and disability, continue to use the medical model, consider PWD as objects of research, and research remains too theoretical (Priestley et al., 2010). Therefore, Goodley and Moore (2000, p. 875) rightly raise questions about "elitism in academia" and argue that research constructed by PWD is "far more innovative, radical and theoretical than that which can be achieved by academic disability researchers in the academy". At present, this is rarely the reality.

Therefore, since "academic spaces are privileged as knowledge generators and that knowledge is also privileged by policy-makers" (Rose, 2017, p. 786), the growing expectations to make the impact of research more visible to civil society may open new opportunities to disability organizations. With a "high level of motivation and readiness to participate in research that will have a positive effect on disabled people's lives in European countries" (Priestley et al., 2010, p. 742) they may contribute to both the methodological shifts in research and the strengthening of civil societies in the post-socialist region.

Further, we will describe the state of civil rights and disability activism in the post-socialist countries, which have quite a different social development history compared to Global North. As noted above, heterogeneous in cultural aspects, the post-socialist countries are, nevertheless, quite similar in terms of institutional arrangements and social policies which were formed by socialist ideology (see, for instance, Romaniuk & Szromek, 2016; Puras et al., 2013). These similarities allow us to compare the developments in these countries in the field of disability rights, despite the slightly different tracks these countries follow.

Civil society and academia in the (post) socialist hemisphere

Conceptualizing a civil society as the web of voluntary associations that interact, are relatively autonomous from the state, articulate values, and interests and create solidarities (Waisman, 2006; Uhlin, 2009) we may state that societies in the socialist hemisphere were deprived of these opportunities. The ideological sphere was subdued to the dictation of the single party and any divergence from the official opinion meant a political and existential crackdown (Tlostanova, 2015). "Voluntary" associations were present in socialist societies as well but could be organized exclusively around the legitimate party's aims. As voluntariness has the power of stimulating individuals' political competence and involvement (Dekker & van den Broek, 1998) in the context of political autocracy it was too threatening. Moreover, new social initiatives were not possible without public discourse, but in societies of the socialist block, the public discourse was ideologically biased and used to subordinate the roles of individuals, such as PWD, who could not fully participate in the building of socialism (Von Seth, 2011).

The upheaval (Gorbachev's "Perestroika") and the collapse of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s fueled the first disability activism. It is said that the emergence of Poland's Solidarity in 1980 was the first seed of civil society in the socialist bloc (Weigle & Butterfield, 1992). International donors followed Putnam's (1993) belief that democratic participation and good governance are immediate outcomes of the proliferation and participation in non-governmental organizations. Large amounts of money were spent by international donors to build, strengthen, and support non-governmental organizations, fund their activities, and thus strengthen the civil society (Ishkanian, 2008). After the "Perestroika", care institutions in former socialist countries for some time remained unchanged, strived to maintain their status quo, and resisted their reorganization into community-based services (Puras et al., 2013). Nevertheless, the positive results of international support were evident in the growing network of disability organizations. Some of them emerged even before the regime change in the early 1990s and are important actors of disability discourse, including the Hungarian Association for Persons with Intellectual Disabilities, ÉFOÉSZ (established in 1981), the Lithuanian welfare society for persons with mental disability "Viltis" (1989), the Latvian "Rūpju bērns" (1990), the Belarussian "Minsk association of parents who look after children with disabilities" (1991), the Czech "Autistik" (1994), and the Ukrainian "Djerelа" Charity Association for People with Intellectual Disabilities (1994). Their success depended on many internal and external factors, such as leadership and mobilization level inside the organization, presence of the political will, level of awareness in their society, and the support provided by international donors. Some of these organizations developed into influential national umbrella associations and became active members of the international disability movement.

Paradoxically, during this period of transition from the totalitarian regime to democracy, the academic sector was left aside, stagnant, rigorously bound to academic traditions, and less relevant for the reforms (for instance, still focused on the treatment of specific disabilities of pupils instead of analyzing the right to inclusive education). This was due to the fact, that the ideologically unified reality and prescribed "political correctness" 4 in the socialist hemisphere had an inevitable impact on academic freedom. Reflecting on academic freedom as the very core of the mission of the university and the essential element of research Altbach (2001) argues that:

…academic freedom was basically destroyed, first during the years of Nazi occupation and then during the over four decades or more of Communist rule, during which universities were considered arms of the state. Ideological loyalty was expected, (…) [whereas] the academic freedom was seen as a "bourgeois" concept, inappropriate in a socialist society (Altbach, 2001, p. 214).

On the other hand, the academic sector itself demonstrated less interest and capacity for change. After the collapse of the socialist system, it was difficult to overcome traditional approaches to ontological and epistemological issues (Altbach (2001), that is – how to understand the disability itself and how to investigate related issues. This may be another reason why disability organizations and not academics were the locomotives of a disability paradigm change. The complex and ambiguous relationships between the two groups will be discussed further in the article.

Research methods

The selected methods were aimed at examining the extent to which current disability discourses in European post-socialist countries contribute to the implementation of the CRPD and how they influence the situation of PWD in that region. Those included: firstly, interviews with five leading national experts from disability organizations (for qualitative data about the relations between disability activists and academia); secondly, four interviews with disability researchers in the region; and thirdly, a scoping review of the academic articles on disability-related topics.

This triangulation of methods aimed at checking the coherence between academic disability discourse and disability practice. Thus it contributed to the understanding of the process of incorporating the perspective of human and disability rights into science and civil society. The selected methods (further described in detail) made it possible to achieve the complex aim, which could not have been achieved by each separate method alone.

Characteristics of informants – experts in the disability field

The data of experts' attitudes towards the disability discourse was gathered using semi-structured skype interviews (Bryman, 2015). In total, nine experts took part in the research. Five of them represented disability organizations from Lithuania (coded as LT-C), Latvia (LV-C), Estonia (EE-C), Belarus (BY-C), and Ukraine (UA-C), referred to in the text as disability organizations' experts. The experts were selected according to the following set of criteria: practical in-field knowledge of the topic; active participation in disability organizations; having been recognized as a national and/or international expert in the field. All the contributing experts have profound experience in working in respective countries, which covers the period from early 2000. The professional backgrounds of the informants cover academic fields such as social work, law, psychiatry, psychology, as well as personal experience of being a PWD or a caring family member.

Four informants represented the academic sector. Two of them were from Lithuania (coded as LT-A1 and LT-A2); one from Bulgaria (BG-A), and one from Slovenia (SL-A) referred to in the text as academic experts. All the academic experts have numerous publications in high impact international academic journals focusing on disability discourse, disability policy, and implementation of the CRPD. They are involved as experts in international projects, advisory groups at various international organizations, such as the UN Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, different bodies of the European Union, one serves as an advisor to a parliament member (with a disability).

Detailed information about the research aims and the use of data was provided and experts' informed consent received. Anonymity and confidentiality of the respondents were ensured and data protected. The general ethical approval for the research was obtained from the Ethics Commission of the Department of Social Work and Social Welfare at Vilnius University. The semi-structured interviews were based on two types of questionnaire guides: one of them was developed for the representatives of disability organizations, the second focused on the experience of disability researchers. Data were collected from November 2017 to June 2018. The average duration of the interviews was approximately 50 minutes. Interviews were transcribed and then manually coded with a focus on thematic units (Meuser & Nagel, 2009). Key concepts and relationships between them were identified and united into wider categories. Categories were organized, and links between the related categories were established and directly used for description and analysis.

Review of articles from the CRPD perspective

This review was aimed at identifying the main topics and underlying attitudes of current academic discourse in the disability field and its correspondence with the principles of the CRPD. The following exclusion and inclusion criteria were applied (Bryman, 2015):

Inclusion criteria. A combination of words, the so-called search quotes "disability discourse" plus the name of the country was applied as a criterion for the selection of articles for further analysis. This search appeared to be very narrow (26 results per country on average). The quotation marks were dismissed and the search yielded much more results (six thousand for each analyzed country, on average). The search spanned the period between 2007 and 2017 years, taking into account that the CRPD was adopted in December 2006.

Exclusion criteria. During the analysis of titles, abstracts, and the first overview of the articles the following exclusion criteria were applied: articles focused on legal cases, students' qualification papers, and articles in which countries of interest were only mentioned. These were dismissed from further analysis. Books were also excluded as they exceeded the format of the present research.

The review of the articles was conducted in "Google Scholar", which encompassed databases (such as SAGE, Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group, etc.) accessible under the authors' university library license. Selected articles covered academic discourses of Lithuania, Ukraine, Belarus, Latvia, Estonia, Slovenia, Bulgaria, and Russia and were conducted in English, Lithuanian, Ukrainian, and Russian considering the linguistic context of Belarus and Ukraine where the Russian language is widely used in academic papers.

A significant part of the search was conducted in the Russian language. Both terms in Russian – "дискурс инвалидности" (invalidity discourse) and the relevant term "люди ("лица") с ограниченными возможностями" (people/persons with limited abilities), also used in the post-socialist countries, – were used for the search.

The numbers of articles found while applying different strategies of search are summarized in the table below.

The table shows that most of the articles were found under the keywords "disability discourse" and "people/persons with limited abilities"+country.

| Belarus | Estonia | Latvia | Lithuania | Russia | Ukraine | Bulgaria | Slovenia | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| "people/persons with limited abilities" (in Russian) +country | 104 | 15 | 18 | 16 | 670 | 82 | ||

| people/persons with limited abilities+country | 8040 | 3290 | 3060 | 4230 | 16100 | 14800 | ||

| "disability discourse" +country | 6 | 18 | 8 | 20 | 87 | 22 | 27 | 19 |

| disability discourse +country | 1490 | 3960 | 3280 | 3770 | 15000 | 7110 | 8010 | 6260 |

| "disability discourse" (in Russian) +country | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 0 | ||

| "disability discourse" +country (in the national language) | 6 | 14 | 1 | |||||

| disability discourse+country (in the national language) | 657 | 2270 | 611 |

In total, 145 articles were analyzed in the following languages: English (49.7%), Russian (29.7%), Lithuanian (11.7%), and Ukrainian (6.9%). 64.1% of publications were based on the original research of authors and 31.03% - on meta-analysis. 4.1% of articles were informed by media sources and in 2% of the cases, reports on the implementation of CRPD were the source of data.

A questionnaire was developed to guide the review and to identify if CRPD was discussed or mentioned in the article and in what context (in a specific area, such as education, or more generally, such as mentioning the need for the change of social attitudes). Other questions focused on the aim and main topic of the article, concepts used to name PWD, the participation of PWD in the research design, etc. The systematic review was conducted by two researchers. To avoid bias, randomly selected articles (three to four) were exchanged among the authors, repeatedly analyzed, and in case of contention on any issue were discussed to avoid disagreements in the further analysis.

Data analysis: Translating Discourses into Practice

The data were processed using three different levels of analysis: a textual, a contextual, and an interpretive (Ruiz, 2009).

Textual analysis of academic articles was conducted to identify the adherence to CRPD and to account for what is suggested by or hidden in the academic articles. All countries whose academic articles were examined in this research have ratified the CRPD from the earliest Slovenia ratified (2008) to the latest Belarus in 2016. The contextual analysis focused on the socio-political space in which the academic discourse has emerged and in which it acquires meaning. It includes implicit dialogues with other discourses (public, human rights discourse, social attitudes towards PWD, the physical and mental heritage of the socialist ideology). The sociological interpretation of both academic discourse and the experience of disability activists allowed identifying connections among the discourses analyzed and the social-political space in which they have emerged. Sources of information included, but were not limited to, interviews with human rights and disability activists, representatives of NGOs, and academia.

The analysis of the entire data from the perspective of disability rights revealed three distinctive themes. Firstly, there were differences in how the terminology of the CRPD was translated revealing ingrained attitudes to what disability is. Secondly, there was a discrepancy between the information found in academic articles and expert awareness of the CRPD and commitment to its principles, and, lastly, it appeared that the policy of CRPD implementation appeared stuck between the enthusiasm of disability organizations, the indifference of academic community and prudence of policymakers. Further, each of these findings will be discussed.

Terminology and its implications

A stipulation of the term "persons with disabilities" in CRPD reflected the priority given to a person as such over her or his other characteristics. Despite certain doubts of some disability activists concerning the use of the term (as it somewhat negates disability in the identity structure), the term persuasively shifts the focus from the medical to social approach.

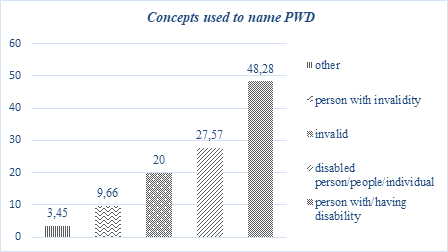

Considering the leading role of science in coining and ingraining the terms, the task was to examine the terminology used in the academic articles. The analyses revealed that they offer a broad variety of definitions of "persons with disabilities'': along with the most widespread "person with/having a disability" (48,28%) other terms such as "disabled person" (27,57%), "invalids" (20%) and "person with invalidity" (9,66%) were also often used. (Figure No. 1).

The figure reveals the popularity of the variety of definitions of persons with disabilities in the academic articles, with the most widespread "person with/having a disability" in almost half of them and the least popular "person with invalidity" in less than 10 percent.

The above-mentioned variety in terminology has methodological and ideological explanations. From the methodological perspective, the analyzed academic papers offered a broad linguistic variety, including English, Russian, Ukrainian, and Lithuanian languages, and this led to a wide-ranging diversity of terminology. The ideological point of view derives from the fact that scholars in their papers rarely refer to the CRPD: less than a quarter of the analyzed academic articles had a clear link to the CRPD, its terminology, values, and principles. Framing the development of disability discourse in Slovenia and its transition from the medical to the social model, the Slovenian expert made a clear terminological distinction between organizations that use the terms "disability" or "invalidity". "Invalidity" organizations were referred to point out the associations which are still attached to the old-fashioned charity model in their fear "to lose their old communism benefits" (SL-A) which, in their opinion, implies a transfer to community-based services. On the contrary, "disability" organizations are considered those which adhere to the principles of CRPD and pursue the human rights perspective (SL-A). The specific term may also refer to the understanding of disability as a question of identity, but in the analyzed articles disability was not discussed as an important component in the construction of identity, despite the term used to define it. Thus the different use of the terms may indicate not only individual preferences or habitual use of the term but ideological approaches to disability issues or emerging identity issues.

In the following chapter, the perspectives of the disability experts' and scholars' on the awareness of CRPD and its influence in post-socialist countries will be discussed and backed by the analysis of academic publications.

Disability discourse: still contributing… to the past

The CRPD seeks to bring about a paradigm shift in disability policy that is based on a new understanding of PWD as right holders and human rights subjects (Degener, 2016). CRPD embraces all fields of life, including employment, education, access to health care and rehabilitation, leisure, sexual and reproductive rights.

Academic experts distinguished at least three levels of disability discourses to a different extent taking place in Eastern and Central European societies: academic discourse, discourse led by disability activists, and political discourse. All these discourses differ from each other and contribute asymmetrically to the awareness and implementation of PWD rights. The Lithuanian expert even estimated the approximate influence towards disability discourse on behalf of different stakeholders in a percent: "I would give 40 percent of influence to disability NGOs, 30 percent to PWD (who are also active members of associations), 10 percent to academia, 15 percent to official institutions, such as ministries and the remaining 5 percent belong to politicians" (LT-A2).

Academic experts emphasized the influence of a deeply entrenched medical model of disability that is still prevalent today. After the collapse of the socialist system, almost all reforms were focused on economic liberalization (Stark & Bruszt, 1998), but there were little efforts to "create welfare state capacity to shape or build social support structures" (BG-A). The charity approach, "blame discourse", (LT-A1) in which PWD are seen as responsible for their life, and paternalism – distinctive features of the medical paradigm – still penetrate the processes of reform.

Scholars perceive the CRPD as "a good example of the indivisibility and interdependence of both sets (1) civil and political and (2) economic, social and cultural of human rights" (Degener, 2016, p. 4). However, experts notice that this is not yet a regular practice in the region: "those local [disability] discourses limit themselves to their own fields, such as education or employment. They fail to rely on the human rights paradigm, they are rather based on the social model which is currently perceived as being outdated and insufficiently reflecting the modern view towards PWD" (LT-A2). Some subjects, such as a barrier-free environment are preferred by representatives of every discourse and are loudly articulated, while other problematic and sensitive themes, including emotional difficulties, reproductive or sexual rights, also the right to independent living, remain marginalized: "But if you go further discussing independent living … this is not discussed [in the society] and still very much traditional" (SL-A).

Discourses on disability rights in post-socialist countries take place in societies still tackling the remains of their socialist past, such as stigmatization and exclusion of vulnerable individuals, lack of respect for universal human rights. Additionally, this socialist legacy is now confronted by a post-socialist move towards neoliberal reforms affecting PWDs and adding to a lack of their social recognition (Mladenov, 2017). However, as academic research is expected to steer the paradigm change, in the chapter below peculiarities of the academic disability discourse will be discussed.

Academic discourse: solitary "talking about yesterday"

According to Matonyte (2006), academic discourses remain the only semantic field where social democratic values are still viable. Therefore, it is plausible to expect that the paradigm of CRPD which is closely related to social democratic values should receive considerable attention in academic papers.

To the informants – academic experts, human rights-based academic disability discourse in the post-socialist region is very marginalized, moreover, the disability itself is marginalized as a theme. Besides, in many post-socialist countries disability discourse is produced not by institutionalized structures or academic bodies, but mostly by individual researchers or is situated in local institutions, therefore is unsustainable and fragmented (BG-A). Moreover, representatives of these sciences see disability through medical indicators, and often do not cooperate for ameliorating the life of PWD in general (SL-A, LT-A2): "All these groups are not exposed or have a hard time thinking about disability as an issue of human rights or social-political model" (BG-A).

All academic experts stressed that it is very difficult for researchers to start seeing disability as a human rights issue and, as claims the Lithuanian informant, there is a lack of academic leaders in the region in that respect (LT-A1). Compared to discourses of disability and political activists, the academic discourse most slowly adapts to the fundamental changes brought forward by CRPD. Predominant academic practices, as well as academic beliefs, are perceived by informants not as strengths, but rather as obstacles that impede changing the academic perspective: "scientists are late [to introduce the human rights perspective] due to their beloved theories; I would call it soaking in their academic pride" (LT-A1). Besides, scholars tend to focus on (dis)abilities of a person, not seeing the larger picture – the structural conditions which lead to disability. In that sense, they are the real "brakes" of the paradigm shift process (LT-A1, LT-A2, SL-A). Researchers do know about CRPD, sometimes even formally mentioning it, but disability discourse in the framework of human rights has not yet become the issue of research: "academic community is not a contributor, unfortunately" (LT-A1).

Analysis of the articles confirms scholars' little attention to the rights issues stipulated in CRPD. Indeed, the main aim of 40% of analyzed articles was to discuss various aspects of PWDs' lives not related to the CRPD, 22.8% – to analyze concepts and language in the disability field, and only 9.7% – to analyze the current state of CRPD implementation. In less than 1% of articles principles of the CRPD were discussed and in less than 1% of articles recommendations for CRPD implementation were provided. Since critical academic discourse is absent in the post-socialist region, despite some positive changes, the major problems of disability rights remain unresolved and there is still a tendency to "reproduce the same problems" in newly created forms of support (e.g., in smaller institutions (BG-A)) or simply to insert "new people in old fashioned institutions" (SL-A). For example, deinstitutionalization in post-socialist countries often becomes trans-institutionalization (Primeau, Bowers & Harrison, 2013). This process means that large institutions are broken down into smaller units - group living houses, but instead of services oriented to the protection of the rights of people with disabilities, only the size of the institution changes.

The views of academic experts were echoed in the interviews with representatives of disability organizations. All experts, committed to the promotion and implementation of PWD rights in the post-socialist countries and involved in the preparation of alternative reports on CRPD, were little acquainted with the academic disability discourse and found it difficult to define its major trends. Three common themes emerged from the interviews, which echoed the results of the articles' analysis: (1) academic discourse in the field of disability remains narrow, fragmented, and focused on particularities of a specific field, such as, for instance, primary school education (LV-C, LT-C1, LT-C2, UA-C). (2) Research often lacks holistic approaches and a general understanding of PWD rights, principles, and values of the CRPD (BY-C, UA-C). (3) The spirit of CRPD and its implications have not yet become the topic of academic interest. In that respect, academic discourse strongly lags behind the civil society organizations which are the first to promote the human rights perspective (LT-A1). This situation is felicitously summarized by the Belarussian expert as "talking about yesterday" (BY-C).

The current situation of disability research in the region can be summarised by the example of expert LT-A2. She paraphrased Deleuze (cited in Vandekinderen, Roets & Van Hove 2014, p. 313), who defined the situation of a researcher in an emerging research field (disability, in this case) by introducing the metaphor of famous Robinson Crusoe after being shipwrecked: "we try to accommodate the new island – the new phenomena – with the instruments from our "old ship". We continue using the same methods, approaches, values, and authors we quote. Relics from the "old ship" might be useful in the new world, but the survival of the researcher (Crusoe) as well as the welfare of the new land largely depend on a researcher's ability to freshly perceive the new environment and invent adequate instruments to interact with it". Therefore, further, it is meaningful to review the analysis of academic papers, which was aiming to identify what new approaches do post-socialist researchers apply in the new "land" – post-socialist disability studies.

Towards the CRPD vision: meeting fragmented needs or implementing rights?

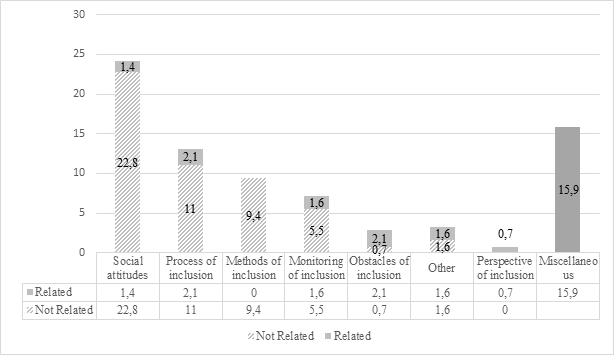

As inclusion takes place in various areas of life, we aimed to identify the fields most covered by academic research. The following Figure No. 2 indicates what aspects of inclusion attracted scientists' attention the most and if / how they relate it to the CRPD.

The Figure No. 2 indicates the most relevant aspects of inclusion and their relation to the CRPD. The academic discourse in post-socialist societies mostly focuses on the social attitudes, processes and methods of inclusion, yet the academic discussion is rarely based on the principles of the CRPD.

Figure No. 2. Aspects of inclusion prevalent in academic articles (in perc.) R – discussion related to Convention, N – not related).

The concept of inclusion from the perspective of the CRPD received little attention in the academic articles. It turns out, that the academic discourse in post-socialist societies does support the idea of the inclusion of PWDs, but the perspective is narrow, fragmented and doesn't cover the main message of CRPD, which is the full realization of a person's rights (in 47.6% of papers no PWD rights were mentioned explicitly). However, a large category "miscellaneous" (15.9%) represented a more holistic approach to PWDs' lives (will be discussed further). Although fragmentary, this category manifested a trend towards a better understanding of PWD rights.

To the academic experts, the narrow understanding of inclusion is mostly challenged by disability organizations, who are pioneers of the human rights perspective. But disability activists cannot always conduct research and lack the legitimacy of science. Moreover, they often seem too radical both to academics and practitioners and are not accepted (LT-A1). Thus, in disability research, PWD remain in a subordinated position, despite a few examples of participatory research (BG-A, LT-A1). The possibility for them to get involved very much depends on the methodological framework of the research: if it is based on the social model, there are more chances that PWD will be involved as co-researchers, but in the frame of the medical approach, one cannot expect too many instances of PWD involvement. "Stuck" on the remnants of a medical model, scholars do not perceive disability activists as equal partners which a social model implies (BG-A). To have PWD as constructors of research agenda there must be very strong disability organizations – "not "traditional" charity, but critical activist organizations" (BG-A, SL-A, LT-A1, LT-A2). Research agenda put forward by PWDs themselves has more potential to promote the real implementation of human rights.

A twofold role of the field leaders: designing a vision for tomorrow

In the 1990s a young child psychiatrist saw the need for strong leadership in disability policy reform in Lithuania. Being a representative of the academic community, he comprehended its limitations. Therefore he approached parents raising children with intellectual disabilities and prompted them to establish an NGO. This initiative was a certain "prototype" of the stance of leading scientists who soon came to understand that by limiting themselves to academic papers, they will not be able to achieve the breakthrough to a new vision, which an acquaintance with Western social developments in the field of disability rights has opened up after the collapse of the socialist system.

Scientists who share the values of CRPD and seek to promote them at different levels of society, find themselves in a situation where to be heard they have to turn from academic publications (and research) to media and other more publicly visible forms of communication (SL-A, LT-A1). In some countries, these leaders are the locomotives of the (de)institutionalization of disability discourse within academia. For instance, it takes the form of disability studies within the faculty of social work (SL-A).

A more advanced approach to disability issues was also manifested in the category "miscellaneous" (15.9%) identified in the articles. This group included such topics as, sexual rights of PWD, civic participation, political participation, subjective life quality, gender issues. In the Russian academic literature, for instance, a new trend is to analyze linguistic aspects of disability, spanning from the pre-revolution period to the present. In Ukrainian papers, one of the emerging topics is the intersection of gender and disability. These themes mark the positive trends to a more holistic understanding of social inclusion. Nevertheless, the philosophy of the CRPD remains outside the borders of a majority of the articles. Therefore, the strategy of scholars to pursue the double role – that of a scientist and a disability activist – seems a timely, appropriate, and hardly avoidable choice.

Impact of disability discourses on policy

The fragmentation of social policies in different fields of life may also be due to the weakness of a comparably new profession in the post-socialist countries – social work, which implies a systematic approach to social problems. Experts claim that due to this reason disability studies will emerge from social work, and not from studies of sociology or political science (BG-A, LT-A2, SL-A). The shortage of attention to some areas of PWD life (formal employment and social assistance) was explained by some experts from disability organizations as a weakness of the social work profession and absence of a substantial academic disability discourse:

"There is no separate institution that would focus on research in the field of disability. Only separate researchers do it, in the frame of established disciplines… but social work, for instance, is not considered a science here… there is no institution, which investigates social problems of PWD" (UA-C).

One of the solutions – the establishment of a separate social policy research institution under the Ministry of Social Welfare – was noted by the Slovenian expert. However, independent disability researchers perceive it as a negative development, as an attempt to monopolize the disability discourse and subordinate it under political decision making (SL-A). This opinion echoes the view of the Lithuanian expert who sees political discourse as exclusively monopolized by ministries of social security or social welfare, which indicates that disability discourse is still framed in a charity based and medical approach. A very strong institutionalized system of care confirms it. Moreover, "the money received from the EU is further used for the institutional care system, which is a stigma of all post-socialist areas" (LT-A1).

The decreasing role of academics and their neglect on the political level is manifested in the communication schemas. For instance, before designing a new law or a new program, politicians tend to approach the so-called "invalid organizations" and persons who are closer to the governing political parties instead of researchers (SL-A). Consequently, lack of appropriate funding limits researchers' opportunities to conduct large scale research, and provide academic evidence. This situation results in quite a superficial collection of data, which does not require much time and resources (SL-A, LT-A1, LT-A2) and contributes to a "vicious circle" of publications that do not break through the old-fashioned concepts and paradigm. The unavailability of timely and relevant independent academic research leads to fewer possibilities to identify priorities for disability policy, allocate resources, monitor the effectiveness of new disability policy, and assess the success of pilot projects.

Discussion

Disability discourse is a result of an enduring exchange of arguments and beliefs between disability organizations, media, politicians, and scholars. Each participant of this discourse is driven by various motives and pursues its own goals. Nevertheless, all three actors have their assets and potentials to contribute to and influence both the discourse and each other.

Analysis of the situation in the post-socialist region demonstrates a huge imbalance of power between the organizations, politicians, and scholars when defining and promoting disability discourse. The official discourse is shared between the Ministries of Social Affairs and disability organizations. The discourse offered by the Ministry is charity-oriented and focuses mainly on social benefits and services. Whereas disability organizations aim at stepping over the charity model and mainstreaming disability as a horizontal priority, crossing all areas of life.

Under the circumstance of such a discrepancy between an immediate revolution (as requested by disability organizations) and vague evolution (as implemented by the politicians) scholars could assume the important role of an impartial mediator between both conflicting parties. Nevertheless, our research data shows a weak and undefined role of scholars in the development of disability discourse in the post-socialist area. Scholars' papers provide a fragmented understanding of particular disability issues and do not contribute to a holistic high-level disability discourse, which would reflect the awareness of PWD rights in all areas of life as the main prerequisite for paradigmatic changes.

Scholars cautiously presume their pro-active role in the implementation of the CRPD, although "the convention has invited scholars to change radically and see PWD from a new perspective, as rights holders" (LT-A1). In those rare cases when members of academia choose to actively participate in the disability discourse and advocate for the rights of PWD, they cross the boundaries of academia and often affiliate with the disability organizations. It is worth noticing, that such examples of a combined background become very successful cases of disability rights advocacy and evolve into a representation at the leading international disability organizations, thus shaping disability policy at the international level.

Conclusion

Responses to the CRPD in the analyzed post-socialist countries reflect difficulties that politicians and academia face in integrating the rights-based approach into policies and research. Our research revealed that the above-discussed trends of how disability activism was developing in post-socialist countries were similar to the phases in Global North (see Blanck, 2004). However, the challenge for post-socialist academia and its relations with disability organizations was that faced with free access to Western approaches and models scholars often failed to absorb their ideological content limiting themselves to its external forms (wordings).

Political actions and academic research is still at odds with the expectations of persons with disabilities to be approached as subjects of universal human rights. The triangle of these three actors – disability organizations, politicians, and scholars – is hardly one of love, but one of misunderstanding, demands, or (non)deliberate omissions of the main principles of CRPD. In this triangle, the enthusiasm of PWD organizations remains the cornerstone, on which their new life is slowly built. However, the lack of groundbreaking research on the current situation of PWD in the perspective of human rights has a negative impact on political will and overall capacity to adopt the spirit of the CRPD in practice. Further research can focus on the emergence of disability studies in the universities of post-socialist countries; the role of international advocacy groups in the activities of disability organizations could also shed more light on their interaction with academic actors.

Limitations

Due to linguistic reasons, the authors could not access the research papers in all languages of the post-socialist region, thus it may be that on the level of each country a disability discourse has more advanced content than the articles have shown. On the other hand, the informants (leading experts of the academic field) confirmed the findings of the article analysis. The paper could also have benefited from insights by academicians with disabilities, yet they are rare in the post-socialist region and the authors couldn't reach any of them.

References

- Altbach, P. G. (2001). Academic freedom: international realities and challenges. Higher Education, 41, 205-219. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026791518365

- Barnes, C. & Mercer, G. (2006). Independent futures. Creating user-led disability services in a disabling society. Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research, 8(4), 317-320. https://doi.org/10.1080/15017410600973523

- Blanck, P. D. (2004). Disability civil rights law and policy. Thomson/West.

- Bryman, A. (2015). Social research methods. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Cox, N. & Webb, L. (2015). Poles apart: does the export of mental health expertise from the Global North to the Global South represent a neutral relocation of knowledge and practice? Sociology of Health & Illness, 37(5), 683-697. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.12230

- Danieli, A. & Woodhams, C. (2005). Emancipatory research methodology and disability: a critique. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(4), 281-296. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557042000232853

- Davis, L. J. (2016). The disability studies reader (5th ed). Routledge: Taylor & Francis. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315680668

- Degener, T. (2016). Disability in a human rights context. Laws, 5(3), 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws5030035

- Dekker, P. & Broek van den A. (1998). Civil society in comparative perspective: involvement in voluntary associations in North America and Western Europe. International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 9(1), 11-38. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021450828183

- Devlieger, P. (2003). Rethinking disability: the emergence of new definitions, concepts and communities. Garant.

- Dimitrov, M. (2018). In Pictures: Bulgarians Demand Better Welfare for People with Disabilities. Retrieved from https://balkaninsight.com/2018/07/30/bulgaria-protest-disabilities-07-30-2018/

- Goodley, D. &. Moore, M. (2000). Doing disability research: activist lives and the academy. Disability & Society, 15(6), 861-882. https://doi.org/10.1080/713662013

- Hughes, G. (2010). Political Correctness: a history of semantics and culture. Wiley-Blackwell.

- Ishkanian, A. (2008). In M., Albrow, H. K., Anheier, M., Glasius, M., Price & M., Kaldor (Eds.) Global civil society 2007/8: communicative power and democracy. London: Sage.

- Longmore, P. K. (1995). The second phase: from disability rights to disability culture. Retrieved from http://www.independentliving.org/docs3/longm95.html

- Lubovsky, V. I. (1974). Defectology: The science of handicapped children. International review of education, 20(3), 298-305. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01666611

- Matonyte, I. (2006). Why the notion of social justice is quasi-absent from the public discourse in post-communist Lithuania. Journal of Baltic Studies, 37(4), 388-411. https://doi.org/10.1080/01629770608629621

- Mayerson, A. B. (1989). Testimony on behalf of the disability rights education & defense fund concerning the Americans with disabilities. Act of 1989. Retrieved from http://dolearchivecollections.ku.edu/collections/ada/files/s-leg_752_004_all.pdf

- Meuser, M., & U. Nagel. (2009). The expert interview and changes in knowledge production. In A., Bogner, B., Littig & W., Menz (Eds.). Interviewing experts (pp. 7-43). Palgrave: Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230244276_2

- Mladenov, T. (2017). Postsocialist disability matrix. Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research, 19(2), 104-117. https://doi.org/10.1080/15017419.2016.1202860

- Odeh, L. E. (2010). A comparative analysis of global north and global south economies. Journal of Sustainable Development in Africa, 12(3), 338-348. Retrieved from https://www.academia.edu/23135887/A_Comparative_Analysis_of_Global_North_and_Global_South_Economies_67

- Priestley M., Waddington, L. & Bessozi, C. (2010).Towards an agenda for disability research in Europe: learning from disabled people's organisations. Disability & Society, 25(6), 731-746. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2010.505749

- Primeau, A., Bowers, T.,G. & Harrison, MA. (2013). Deinstitutionalization of the mentally Ill: evidence for transinstitutionalization from psychiatric hospitals to penal institutions. Comprehensive Psychology, 2. https://doi.org/10.2466/16.02.13.CP.2.2

- Puras, D., Sumskienė, E., Veniutė, M., Murauskienė, L., Sumskas, G., Dirzienė, J., Juodkaitė, D., Sliuzaitė, D. (2013). Mokslo studija „Issukiai igyvendinant Lietuvos psichikos sveikatos politika". Retrieved from http://naujienos.vu.lt/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/issukiai-igyvendinant-Lietuvos-psichikos-sveikatos-politika.pdf

- Putnam, R. D., Leonardi, R. & Nanetti, R. Y. (1993).Making democracy work. Civic traditions in modern Italy. Princeton: Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400820740

- Rasell, M. & Iarskaia-Smirnova, E. (eds.). (2013). Disability in Eastern Europe and the Former Soviet Union: History, Policy and Everyday Life. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315866932

- Romaniuk, P. & Szromek, A. R. (2016). The evolution of the health system outcomes in Central and Eastern Europe and their association with social, economic and political factors: an analysis of 25 years of transition. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-016-1344-3

- Rose, D. (2017). Service user / survivor-led research in mental health: epistemological possibilities. Disability & Society, 32(6), 773-789. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2017.1320270

- Rosner, I. D. (2015). From exclusion to inclusion: involving people with intellectual disabilities in research. TILTAI, (72)3, 119-128. https://doi.org/10.15181/tbb.v72i3.1170

- Ruiz, R. J. (2009). Sociological discourse analysis: methods and logic. Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 10 (2).

- Ruskus, J. (2002). Negalės fenomenas. Monografija. Šiauliai: Šiaulių universiteto leidykla.

- Shakespeare, T. (2010). The social model of disability. In J.D. Lennard (Ed.). The disability studies reader (pp. 266-273). Retrieved from http://thedigitalcommons.org/docs/shakespeare_social-model-of-disability.pdf

- Shoot, B. (2017). The 1977 disability rights protest that broke records and changed laws. Retrieved from https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/504-sit-in-san-francisco-1977-disability-rights-advocacy

- Stark, D. & Bruszt, L. (1998). Postsocialist Pathways transforming politics and property in East Central Europe. Cambridge University Press.

- Sumskiene, E. (2017). Advocacy for children with intellectual disabilities: the case of the Baltic States. In K., Fabian, E., Korolczuk (Eds.). Rebellious parents: parental movements in Central-Eastern Europe and Russia (pp. 248-276). Bloomington: Indiana University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt2005wgn.13

- Sumskiene, E., Gevorgianiene, V., & Geniene, R. (2019). Implementation of CRPD in the Post-Soviet region: between imitation and authenticity. In: M., Berghs, T., Chataika, Y., El-Lahib, K., Dube (Eds.). The Routledge handbook of disability activism (pp. 385-398, chapter). London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351165082-31

- Tlostanova, M. (2015). Between the Russian/Soviet dependencies, neoliberal delusions, dewesternizing options, and decolonial drives. Cultural Dynamics, 27(2), 267-283. https://doi.org/10.1177/0921374015585230

- Uhlin, A. (2009). Which characteristics of civil society organizations support what aspects of democracy? Evidence from post-communist Latvia. International Political Science Review, 30(3), 271-295. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512109105639

- Vandekinderen, C., Roets, G. & Hove, Van G. (2014). The researcher and the beast: uncovering processes of othering and becoming animal in research ventures in the field of critical disability studies. Qualitative Inquiry, 20 (3), 296-316. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800413489267

- Von Seth. R. (2011). The language of the press in Soviet and Post-Soviet Russia: creation of the citizen role through newspaper discourse. Journalism,13(1), 53-70. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884911400844

- Waisman, C. H. (2006). Autonomy, self-regulation, and democracy: Tocquevillean Gellnerian perspectives on civil society and the bifurcated state in Latin America. In R. Feinberg, C. H. Waisman & L. Zamosc (Eds.), Civil society and democracy in Latin America (pp. 17-33). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781403983244_2

- Weigle, M. A. & Butterfield, J. (1992). Civil society in reforming communist regimes: the logic of emergence. Comparative Politics, 25(1), 1-23. https://doi.org/10.2307/422094

- Winter, J. A. (2003). The development of the disability rights movement as a social problem solver. Disability Studies Quarterly, 23(1), 33-61. https://doi.org/10.18061/dsq.v23i1.399

Endnotes

-

The post-socialist region includes Central and East European transition state economies and politics (Stark & Bruszt, 1998) (Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Croatia, Hungary, Kosovo, Macedonia, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, Serbia, Slovenia), all successor states of the Soviet Union (Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Estonia, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Latvia, Lithuania, Moldova, Russian Federation, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Ukraine, and Uzbekistan) and Mongolia.

Return to Text -

Defectology is an integrated scientific discipline that embraces the study and education of children and adults with disabilities (Lubovsky, 1974, pp 298).

Return to Text -

The concept of "Global North" represents the economically developed societies of Europe, North America, Australia, Israel, South Africa (f.i., Odeh, 2010), and is often used interchangeably with the concept "West" (f.i., Cox, Webb, 2015).

Return to Text -

"political correctness" is the term used to describe a certain code of language which aims not to disturb the status quo of the dominant ideological paradigm (f.i, Hughes, 2010).

Return to Text