We were honored to receive the senior scholar award and delighted to be invited to submit an article for this issue of the DSQ. In this paper, we present our recent thinking about disability as disjuncture and the significant role that design and branding play in creating this ill-fit. However, simultaneously, design and branding provide the contemporary opportunity and relevant strategies for rethinking disability and social change, and healing disjuncture. As always, this thinking is a work in progress with invitation for criticism and dialogue. We begin by setting the chronological and intellectual context that informs our ideas. We then clarify Disjuncture Theory and link design and branding to revisioning a globe in which disjuncture is healed by contemporary relevant theorizing and praxis.

Setting the Context

Reflecting on the 21st century reveals communities which are no longer defined by their geographic or even physical boundaries. Individuals can be in several places at one time (Bugeja, 2005), can increasingly participate in global events when they happen through viewing them in action on screens that can even be carried in a pocket. Work no longer needs to take place in a physical "workplace." We can create and revise our own virtual identities, appearances, functionality, and methods of interacting. We can shop internationally from our living rooms and enter virtual and actual theme parks that provide us with familiarity and comfort. We can communicate with great immediacy across the globe in languages that we may not even speak. We text message, e-mail, log on, blog, podcast, and become actors on virtual stages of our own films. We can access libraries, museums, across the globe from our homes and can meet face to face even if we are physically situated in different continents. Time is no longer simply a linear chronological measurement. We live among people who originated from distant geographic locations throughout the globe. And we can uncouple ourselves from our bodies as we interact, earn, play, and even engage in sex in virtual spaces.

Critical to thinking and theorizing about disability within these contemporary chronological times, we challenge the intellectual status quo of separate disciplines and discuss concepts such as intersectionality, symbols, theming (Bryman, 2004; Lukas, 2007), and constructed realities. The uncertainties and relativism of recent intellectual trends have been provocative of new thinking in which unlikely disciplines mingle and create new opportunities for context-relevant thinking and informed action. We now discuss these contemporary themes within disability studies.

Postmodernism and Post-postmodernism within Disability Studies

Over the past few decades, postmodern theories that emerged in opposition to modernism caught the intellectual gaze of many disability studies theorists. Because postmodernism challenged the tyranny of normalcy (DePoy & Gilson, 2009) post-modernism provided both power and comfort in denuding grand narratives which disparage bodies and experiences that do not fit within + two standard deviations from the mean on measures based in traditional longitudinal and behavioral theories. While postmodernism opened a portal through which disability studies could oppose the medicalized 20th century notion of disability, its carnivalesque gaze and focus on the nonsense of language and symbol (Baudrillard,1995) have left too many vacancies when looking to theory to inform human rights and equality of opportunity for groups which have historically been excluded, disenfranchised, or exploited for profit.

Despite its limitations, by dismantling narrative and theorizing its political ambiguity and even duplicity, post-modernism has left important intellectual rubble to be refitted into new theoretical configurations. What has appealed to us about postmodernism and its successors is simultaneous acceptance of diverse bodies of evidence beyond traditional positivist designs but including them as well, and its eschewal of prescribed world-views. These elements can support new theorizing that does contemporary-relevant intellectual and applied work. What we mean by work is the intellectual, analytical and knowledge base to inform understanding and equality of human rights.

Post-post modernist theorists are mining the disparate gems in the debris that the postmodernists left as they interrogated and unpacked enlightenment thinking. The post-postmodern contemporary genre for us integrates the "best of all explanatory worlds" by synthesizing the advantages of diverse fields. Post-postmodernism has gifted disability explorations and explanations with both intellectual and utilitarian richness. Consider for example the metaphoric propinquity of the designer disability items, orthopedic shoes, queerness, and evolutionary theory (Fries, 2007). Fries elucidates stunning relationships among his own travels and phylogenic theories of natural selection, legitimately reintegrating science into discussions of disability. Similarly the neurodiversity literature allows for the reintroduction of biology into explanations of disability while advancing progressive views in so doing. As example, using this postpostmodern view, diagnoses of brain disorder such as bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, autism, and so forth are reframed as diverse rather than as pathological (Antonetta, 2007; Seidel, 2004-2009).

Bolstered by post-postmodern scholarship, our recent work proposing two frameworks, "Disability as Disjuncture" and "Disability as Logo" have the potential to be theoretically robust in informing innovative contemporary responses aimed at equalizing human rights (DePoy & Gilson, 2006; Gilson & DePoy, 2007; 2008). We turn to these now.

Disability as Disjuncture

Building on seminal works over the past decade, Disjuncture Theory indicts the interstices between environment and body as the locus for disability. As early as 1999, National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research published the following explanation: "disability is a product of the interaction between characteristics of the individual (e.g., conditions or impairments, functional status, or personal and social qualities) and the characteristics of the natural, built, cultural, and social environments" (NIDRR, 2007). This synthetic explanation positions disability as mobile and context embedded but fails to identify the point or range at which the "interactive product" moves from ability to disability. Within NIDRR's viewpoint, the atypical body remains the habitat of disability as depicted in the parenthetical clarifier in the definition above.

Davis (2002) also was influential in looking at disability beyond the "body or environment" binary. Proceeding on his position that disability is an unstable category in need of reconceptualization, Davis posited the revision of the category to include every "body" regardless of its current status as disabled or not. This important viewpoint foregrounded the limitations of outdated models of identity politics that crafted policy responses for sub-populations even with the recognition that everyone can join the membership roster of disability. Similar to NIDRR's definition, Davis retained the body as the entry point into the disability club, referring to Christopher Reeve as exemplary of how quickly one can change embodied status.

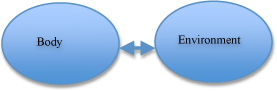

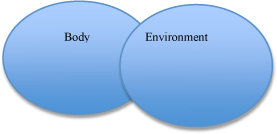

This foundational work precedes and shapes disjuncture as one of many explanations that could form a solid axiological as well as praxis foundation for legitimate disability determination and response. Unlike NIDRR and Davis, however, we do not look to the body for the initial entrance into disability. Rather, Disjuncture Theory locates disability at the intersection of bodies and environments. Through this lens, disability is an ill-fit between embodied experience and diverse environments in which bodies act, emote, think, sense, communicate, and broadly experience. Disjuncture Theory therefore recognizes body and environment as equal vestibules leading into the category of disability. Figures 1 and 2 visually represent disjuncture. As depicted below, disjuncture is a continuum rather than a binary, with ascending degrees of separation between environment and body denoting more severe disjuncture and visa versa.

Figure 1 - Extreme disjuncture

Figure 2 - Moderate disjuncture

Full juncture, depicted in Figure 3, is the non-example of disability and thus is the desirable that drives our theorizing and application to praxis. In this state, embodied presence fits well within environmental features.

Figure 3 - Juncture

Curiously, our initial thinking about disjuncture emerged from a conversation in a disability studies class about design, beginning our foray into design as an important element of disability as well as a critical consideration in healing disjuncture.

Design

Design is a complex construct which has been increasingly used to describe abstract and concrete human intention and activity, and to name a property of virtual, physical, and even abstract phenomena. Figure 4 presents representative lexical definitions of design.

Figure 4 - Definitions of Design

- To create, fashion, execute, or construct according to plan : DEVISE, CONTRIVE (Merriam Webster, 2006-7)

- Means any design, logo, drawing, specification, printed matter, instructions or information (as appropriate) provided by the Purchaser in relation to the Goods (http://simply-small.com/tandc.html)

- Design is a set of fields for problem-solving that uses user-centric approaches to understand user needs (as well as business, economic, environmental, social, and other requirements) to create successful solutions that solve real problems. Design is often used as a process to create real change within a system or market. Too often, Design is defined only as visual problem solving or communication because of the predominance of graphic designers. (http://www.nathan.com/ed/glossary/)

- The plan or arrangement of elements in a work of art. The ideal is one where the assembled elements result in a unity or harmony. (http://www.worldimages.com/art_glossary.php)

- Both the process and the result of structuring the elements of visual form; composition. (http://www.ackland.org/tours/classes/glossary.html)

- A clear specification for the structure, organization, appearance, etc. of a deliverable. (http://www.portfoliostep.com/390.1TerminologyDefinitions.htm)

- Intend or have as a purpose; "She designed to go far in the world of business" (http://wordnet.princeton.edu/perl/webwn)

- A plan for arranging elements in a certain way as to best accomplish a particular purpose (Eames, 1969 in Munari, Eames, Guixe & Bey, 2003)

As reflected in the definitions and consistent with post-postmodern thought, design is purposive and may refer to decoration, plan, fashion, functionality, and influence. What is evident in the diverse definitions is the broad scope of phenomena to which design applies, including but not limited to the activities of conceptualizing, planning, creating, and claiming credit for ones ideas, products, and entities as well as the inherent intentional or patterned characteristics of bodies, spaces, and ideas (Margolin, 2002; Munari, Eames, Eames, Guixe, & Bey, 2003).

Despite the ubiquitous and diverse use of the term, of particular note is the post-postmodern commonality in all definitions of design as purposive and intentional. That is to say, design is not frivolous but rather is cultural iconography which is powerful, political, and is both shaped by and explanatory of notions of standards, acceptability, membership, and desirability (Foster, 2003; Munari et al., 2003). Purposive design therefore has the potential to shape constraint, maintenance of the status quo or profound change.

It is therefore curious that built and virtual environmental and product design standards are constructed around Enlightenment ideals of the human body, its balance, proportion, emphasis, rhythm, and unity (DePoy & Gilson, 2008; Margolin, 2002). This practice creates disjuncture and thus significant disability for numerous bodies, including many that fit within the typical ranges.

But the built environment is not the only target of design. Bodies themselves are "designed" through medical measurement and practice, fashion, fitness, education, counseling, and so forth. As example, consider the recent book by Little and McGuff (2008) entitled "Body by Science." This title and the contents propose the role of empirically supported strategies to "design" the ideal body shape, tone, and even energy level for anyone who is willing. This trend is particularly relevant to the 21st century in which design has been enthroned not only as an aesthetic but also as cultural icon, logo, empirical method, and signifier of value. This point provides the segue to branding as simultaneously instigative of disability containment and liberation from stigma.

Disability as Logo: Branding

In contemporary western economies, design is closely related to branding. Given the emergence of branding from the fields of marketing and advertising, brands within this constrained conceptual framework are defined as the purposive design and ascription of logos to a product for the intent of public recognition, addition of value, and consumption, Of particular importance to disability explanations within the scaffold of branding is the construct of value-added. Interpreted broadly, the addition of value does not necessarily imply an increase or elevation, but denotes the cultural inscription of value that can span the continuum from extremely pejorative to most desirable.

More recently, scholars have enlarged the definitional scope of branding as a critical culturally embedded symbolic set that commodifies and reciprocally represents and shapes value, ideas, and identities. Brands are design stories that unfurl and take on meaning as they are articulated and shared by multiple authors, so to speak. Because symbolism and dynamism both inhere in branding, Holt (2004) has suggested the term cultural branding, which elevates brands to the status of icon, and marker of identity and idea. While Holt's term is relatively new, the notion of branding as explanatory of one's cultural, social, and individual identity and comparative social worth was originated in the early and mid 20th century by thinkers such as Horkheimer, Adorono, Noerr, and Jepgcott (2002) and McKluhan and Fiore (2005). Although divergent in ontology and domain of concern, these scholars were seminal in introducing branding as an identity-inscribing and projecting entity. That is to say, through the process of choosing and adopting cultural iconography in the form of products, fashions, food, music, and so forth one ostensibly defines the self and displays value to others (Holt, 2004).

While grand narrative suggests that brands can be chosen to depict and publically display a preferred identity(McLuhan & Fiore, 2005) we do not necessarily agree with this principle as universal. Rather through post-postmodern analysis, the purposive nature of design and branding can be revealed as manipulating individuals and groups into believing that they can and do autonomously choose their identities when they cannot. The conceptual portal of design and branding viewed through a teleological lens splays open the purposive, political, and profit-driven nature of embodied labeling, identity formation and recognition, stereotyping, and responses that explain disability and give meaning to it both as a category and as a fiscally productive market. The explanatory importance of this conceptual framework lies in the processes and purposes of design and branding as deliberate, complex, and potentially able to manipulate meaning of self, others, and categories (Licht & O'Rourke, 2007). The result of branding, which can span exploitation through liberation, is dependent on depth of understanding as well as skill in putting this market strategy to work.

In previous work, we have examined how design of visuals, such as objects, brand those who use disability specific products as disabled (DePoy & Gilson, in press). However, design and branding reach out more expansively and abstractly in explaining disability populations and affixing their value. Visual logos do not have to be present in order for disability to be recognized and valuated or "branded." Understanding disability through the powerful contemporary post-post modern lens is particularly timely and thought provocative within advanced global market environments (DePoy & Gilson, in press; Pasquinelli, 2005).

In a recent presentation that we gave at the Society for Disability Studies in 2009, a participant remarked that marketing theory did not do explanatory justice to understanding disability as a cultural group that experiences social discrimination and exclusion. In concert with Riley (2006) we respectfully disagreed, suggesting that in the 21st century and consistent with post-postmodern thinking, disability is no longer exempt from the market economy, business, and its design and branding processes (Adair, 2002; Pullin, 2009; Riley, 2006). Rather this synthetic lens is seminal to explaining disability as marked, circumscribed, and commodified by designated products, spaces, and abstracts that not only brand its members but position them as a target market segment ripe for commodification and economic exploitation. However, this complex analysis reveals new actionable pathways to social change as well.

As early as 1992, Gill and then Albrecht — in 2001 — published scholarship that revealed the economic advantage derived from disability by providers, professionals, product manufacturers, and so forth. DePoy and Gilson (2004) referred to this phenomenon as the disability industry and more recently, building on the work of Lukas (2007) and Bryman (2004), the disability park (DePoy & Gilson, 2008) in which economic survival and profit drive design of themed or branded spaces which too frequently trump the goals of facilitating meaningful, full participation in community, work, recreation, and civic life for people who are considered or identify themselves as disabled.

Our more recent thinking asserts that in the current global context, disability, economic advantage, and value-added design not only can co-exist but must do so in order to reveal and dismantle the disability park and replace it with value added branding for diverse bodies. Policy has a significant role in this design and branding effort as we now discuss.

Policy as Designed and Branded Disability

Aligned with disability products, spaces, and services which serve to brand those who use and inhabit disability geographies and parks, the very design of disability policy as a separate entity is an exemplar of abstract (non-visual) branding through segmentation. We refer to this policy segment as disability explicit, in that policies that exclusively target disability retain the abstract of the disability park as separate. However, disability policy is not located solely within the disability explicit world. Policy responses to disability can be located within identity politic policies that create "special" responses for population subcategories (referred to as disability-embedded policy), or in disability implicit policies which do not name disability but design it as devalued and undesirable through other political mechanisms such as measurement, prevention, and so forth. (We are not suggesting that prevention of injury and illness at any stage of human existence is pejorative. Rather, we are urging a post-postmodern examination of policy such as public health strategies, particularly with regard to how they design and brand the value of designed bodies, populations, and behaviors and then hang valued outcomes on these policy doorposts.)

Within disability-explicit and some embedded policy, two major lexical divisions exist: policies that guide the provisions of disability services and resources, such as the Social Security Disability Insurance Act (SSDI) (established by the Social Security Amendments of 1956, in the United States, and more recently those, such as the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA, 1990) The ADA Amendments Act (2008), and the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities that purport to protect and advance the civil rights of populations that are considered or identity as legitimately disabled.

Building on this binary taxonomy, we suggest that that policy is much more complex than its explicit verbiage and articulated outcomes. As noted by Kymlica (2007) in his recent analysis of multiculturalism, global human rights policy is plagued by two overarching problems. The first is the failure of current categorical frameworks to do viable work in carving up humanity into useful categories. Kymlica's assertion provides one of the foundational pillars of our view, as we question the legitimacy of so many diverse and vague explanations for disability and thus the usefulness of the category for achieving the asserted purposes of full participation.

The second problem identified by Kymlica (2007) is the time sequence of designing and implementing targeted and generic policy. Applied to disability, we suggest that targeted distributive and protective legislation in itself designates and designs legitimate disability. Those who qualify for benefits and protections of disability policy are not only defined as disabled if they meet the explanatory criteria, but their lives are designed in order to maintain benefits.

We assert that separate disability policies, which we referred to above as disability explicit policy, institutionalize disability explanations and the disability park by partitioning and "logofying" abstract principles and language and applying them differentially to disabled and non-disabled individuals (Tregakis, 2004). As an example, above we noted that people who are considered disabled are enabled by disability explicit policy to obtain often without cost, but within the disability park, products which are branded as "assistive technology" while non-disabled people who use identical products use technology, or as Seymour (2008) asserts, use items branded as fashionable technology. Consider the need for help that is designed as part of disability identity in the word "assistive" and the inscription of this branded concept in the Assistive Technology Act passed in the United States in late 20th century.

Another consideration regarding the sequencing of targeted and generic policy was illuminated by Badinter (2006) in her discussion of gender equality. She suggested that the maintenance of "specialized rights and policies" negates their articulated aims of equality. This insidious process occurs by surreptitious design in which recipients of resources and rights only granted by specialized policies are defined by their eligibility for protection and thus continue to be branded as victims. Those who are covered under disability policy therefore are designed and branded as vulnerable, in need of specialized assistance, and in the disability park that provides employment and economic opportunity and advantage to providers and disability designers. Analysis of disability explicit and embedded policy reveals it as a grand narrative, a brand of designed identity policy that on the surface speaks of resources and equity, but in essence serves up populations identified or identifying as disabled or otherwise vulnerable to the disability park and thus designs disability by location of service consumer within the park.

Similarly, The UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, a disability-embedded policy in that other vulnerable groups are named as well, while theoretically enacted to raise awareness and reduce discrimination and disadvantage experienced by populations identified or identifying as disabled, is often persuasive in the abstract but lacks substantive content. Thus it is explanatory as well. The presence of specialized and protected policy worldwide and the location of disability adjacent to other groups design all of these groups as needy of legal protection rather than as citizens with the rights and responsibilities afforded to typical citizens.

Both nationally and internationally, we recognize the temporary value of these policies for redressing discrimination and exclusion, particularly in a context in which population specific policies and resources are the predominant distributive model. However, through a post-postmodern lens, the explicit intent of disability explicit and embedded policy is open for interrogation and analysis as the basis to advance social change and equality of opportunity in the long-term, and to move from the oxymoron of population specific equality to population-wide equality and justice.

Theorizing and practice of design and branding, therefore, are not only central but critical in framing responses that we see as promoting full juncture. We therefore urge disability scholars and activists to capture and use design, branding and market theorizing and related praxis not simply to bemoan exclusion and exploitation from others who apply these strategies to design and maintain the disability park but rather to harness these contemporary-relevant ideas and skills to promote positive social change. Referring to Kymlica's (2007) criticisms of categorization and the timing of expanding specialized policy citizen-wide, design and branding have significant potential to redesign and rebrand bodies and environments to produce goodness of-fit and full juncture.

References

- Adair, V. (2002). Branded with infamy: Inscriptions of poverty and class in the United States. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

- Albrecht, G., Seelman, K., & Bury, M. (2001). Disability studies handbook. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Antonetta, S. (2007). A mind apart: Travels in a neurodiverse world. Tarcher.

- Badinter, E. (2006). Dead end feminism. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

- Baudrillard, J. (1995). Simulacra and simulation: The body in theory: histories of cultural materialism (S. F. Glaser, Trans.). Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

- Bryman, A. (2004). The Disneyization of society. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Bujega, M. (2005). Interpersonal divide: The search for community in a technological age. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Davis, L. (2003). Bending Over backwards: Disability dismodernism and other difficult positions. New York, New York: New York University Press.

- DePoy, E., & Gilson, S.F. (in press). Disability by design. Review of Disability Studies.

- DePoy, E., & Gilson, S.F. (2008-2009, Winter). Social work practice with disability: Moving from the perpetuation of a client category to human rights and social justice. Journal of Social Work Values and Ethics, 5(3). Access: http://www.socialworker.com/jswve/content/view/103/66/.

- DePoy, E., & Gilson S. (2008). Healing the disjuncture: Social work disability practice. In K.M. Sowers & C.N. Dulmus (Series Editors) & B.W.White (Vol. Ed.), Comprehensive Handbook of Social Work and Social Welfare: Vol. 1. The Profession of Social Work (pp. 267-282). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- DePoy, E., & Gilson, S.F. (2008). Designer diversity: Moving beyond categorical branding. The Journal of Comparative Social Welfare, 25, 59-70.

- DePoy, E., & Gilson, S.F. (2004). Rethinking disability: Principles for professional and social change. Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks-Cole.

- Fitzgibbon, K. (2005). Who owns the past? New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

- Foster, H. (2003). Design and crime (and other diatribes). New York: Verso.

- Fries, K. (2007). The History of my shoes and the evolution of Darwin's theory. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press.

- Fussell, P. (1992). Class: A guide through the American status system. New York, NY: Touchstone.

- Galician, M.L. (2004). Handbook of product placement in the mass media: New strategies in marketing theory, practice, trends, and ethics. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Gill, C. (1992, November). Who gets the profits? Workplace oppression devalues the disability experience. Mainstream, 12, 14-17.

- Gilson, S.F., & DePoy, E. (2007). DaVinci's ill-fated design legacy: Homogenization and standardization International Journal of the Humanities, 4, http://www.Humanities-Journal.com

- Gilson, S.F., & DePoy, E. (2008). Explanatory legitimacy: A model for disability policy development and analysis. In I. Colby (Ed.). Social Work Practice and Social Policy and Policy Practice. Hoboken, NJ; John Wiley & Sons.

- Gilson, S.F., & DePoy, E., (2005/2006). Reinventing atypical bodies in art, literature and technology. International Journal of Technology, Knowledge and Society, 3, 7, http://www.Technology-Journal.com.

- Holt, D. B. (2004). How brands become icons: The principles of cultural branding. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

- Horkheimer, M. , Adorono, T. Noerr, G.S., & Jepgcott, E. (2002). Dialectic of enlightenment. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Kymlica, W (2007). Multicultural odyssey. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Lefebvre, H. (1991). The production of space. Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

- Licht, A. & O'Rourke, J. (2007). Sound art: Beyond music, between categories. New York, NY: Rizzoli.

- Little, J., & McDuff, D. (2008). Body by science. New York, NY: McGraw Hill.

- Lukas, S. (2007). The themed space: Locating culture, nation, and self. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books.

- Margolin, V. (2002). The politics of the artificial: Essays on design and design studies. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- McLuhan, M. & Fiore, Q. (2005). The medium is the massage. New York, NY: Ginko Press.

- Merriam Webster, Inc. (2009). Merriam Webster Online. Retrieved January 4, 2009, from http://www.merriam-webster.com/

- Munari, B., Eames, C, Eames, R., Guixe, M., & Bey, J. (2003). Bright minds, beautiful ideas. Amsterdam, NE: Bis.

- Nussbaum, M. (2007). Frontiers of justice. New York, NY: Belnap.

- Pasquinelli, M, (2005). An Assault on neurospace. Accessed: http://info.interactivist.net/node/4531

- Phillips, S. (2008). Out from under: Disability, history and things to remember ~ Dressing. Accessed: http://www.rom.on.ca/media/podcasts/out_from_under_audio.php?id=5

- Pullin, G. (2009). Design meets disability. Boston, MA: MIT Press.

- Riley, C. (2006). Disability & business. Lebanon, NH: University of New England Press.

- Salvendy, G. (2006). Handbook of human factors and ergonomics. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- Scott , A.O. (2008). Metropolis now. NY Times Magazine Section, June 9.

- Seidel, K. (2004-2009). Neurodiversity Weblog. Retrieved July 4, 2009, from Neurodiversity.com: http://www.neurodiversity.com/main.html

- Seymour, S. (2008). Fashionable technology; The intersection of design, fashion, science, and technology. Springer.

- Tregaskis, C. (2004). Constructions of disability: researching the interface between disabled and nondisabled people. London, UK: Routledge.

- U.S. Department of Education, Office of Special Education and Rehabilitative Services, National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research. (2007). NIDRR Long Range Plan For Fiscal Years 2005 — 09: Executive Summary. Accessed May 25, 2010 from http://www2.ed.gov/rschstat/research/.../nidrr-lrp-05-09-exec-summ.pdf