Introduction

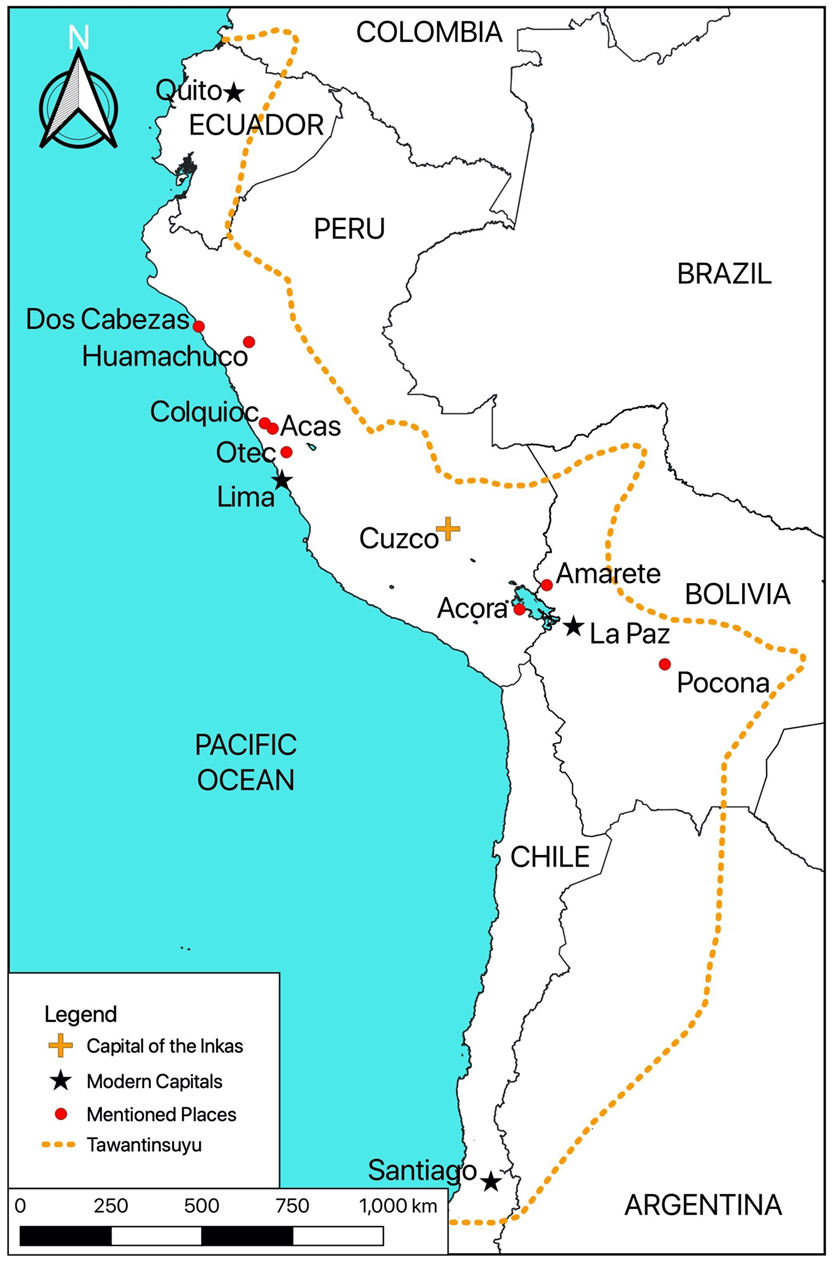

Throughout the late Pre-Columbian Americas, Indigenous people with disabilities and physical differences were treated in a manner different than was typical throughout Europe during the contemporary Late Middle Ages (ca. 1250-1500) and Early Modern (ca. 1500-1800). The Inka Empire (ca. 1400-1533), Tawantinsuyu (Figure 1), particularly had its own social systems that benefited people with atypical bodyminds, referred to in Quechua (Tawantinsuyu's lingua franca) as hank'akuna (sing. – hank'a, pl. – hank'akuna). Once a new society was conquered, the Inkas, when necessary, imposed their ontological view of the hank'akuna and Tawantinsuyu institutionalized measures to ensure care for these subjects within their communities. While the Inka imperial project should not be understood as a universally benevolent entity, their level of inclusivity for hank'akuna is highly unique. In Tawantinsuyu, an hank'a's atypical body configuration was how they derived specific forms of power; under the Spanish, these individuals were stigmatized and forced into European social systems. However, Inka understandings of bodily difference and bodily configuration are still relevant to some modern Quechua and Aymara societies whose social constructions of inclusivity have survived erasure from Spanish colonialism.

Figure 1. A map of Tawantinsuyu's limits in relation to modern nation-state borders (map by the author; boundaries of Tawantinsuyu partially based on D'Altroy 2015: Fig. 4.1). Tawantinsuyu encompassed parts of modern Peru (with its capital in Cuzco), Bolivia, Chile, Argentina, Ecuador, and Colombia.

Disability Studies and Its Intersection with Indigenous Studies

Disability is a social construction that reflects context-specific cultural concepts. To better understand the cultural nuance behind such perceptions, it is important to recognize local understandings of body forms and differences (Devlieger 1999; Mutua 2001). The concept of disability is constantly changing throughout history (Stiker 1999; Hubert 2000); who dominates the historical narrative affects interpretations of the past, which is problematic with colonized Indigenous societies in which local narratives were controlled by colonizers (Stoler 2009; O'Brien 2017). Researchers must disentangle experiences of historically marginalized voices to understand traditions beyond the social norms of dominant classes (Strong 2017; Barclay 2017); with this in mind, there can be explicit differences between Western biomedical approaches to disability and Indigenous ontologies of how such individuals fit within their communities (Kasonde-Ng'andu 1999).

Over the past generation, there has been an increased focus on the historical experience of Indigenous Americans with disabilities (e.g., Joe 1980; Senier 2017; Burch 2021). There is a growing body of literature about Indigenous social constructions of disability throughout the Pre-Columbian Americas. Arguably, the most well-studied region is Mesoamerica, particularly concerning dwarfism amongst the Mayas (e.g., Miller 1985; Coggins 1994; Prager 2002; Bacon 2007). However, more recent studies have reviewed the geographic diversity of Mesoamerican representational trends of disability and how such perceptions have changed throughout time (e.g., Ponce and Hechler 2016; Gassaway 2017).

Understanding Difference in the Pre-Columbian Andes

Archaeological remains and artistic representations of hank'akuna in Inka contexts as well as of then-contemporary and earlier Andean cultures help in comprehending Andean perceptions of disability. Many past Andean societies recreated their ontological visions of people with physical differences in their material world. Throughout the Andes, one can find representations of people with dwarfism, kyphosis, visual impairment, and amputations. Many cultures showcased these effigies as being active – playing music, holding ritual paraphernalia, and partaking in religious ceremonies (Hechler and Pratt 2015). The Inkas typically favored representing individuals with pronounced kyphosis (Figure 2), whose physical forms were fetishized in ceremonial effigies, statuary, and ornaments which could be expressed through various mediums – precious metals like gold and silver, sculpted via clay, and carved from rock.

Figure 2. These two figures of male k'umukuna (individuals with kyphosis) are examples of the type of jovial representations that the Inkas created, with these respective effigies carrying and riding llamas. On the left side is a man with kyphosis, carrying a Llamita. (Inka. Rodadero, Cusco, Peru – 2443. Montes Collection. Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, IL: Image No. CL0001_2443_Overall_XMP2, Cat. No. 2443, Photographer Jessica Jackson-Brown). On the right a photograph shows a silver figure of a man with kyphosis riding a llama. (Inka. Choqechaka, Cusco, Peru – Catalogue No. A210366. Department of Anthropology, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution. Image courtesy of the National Museum of Natural History).

Compared to Mesoamerica, Pre-Columbian Andean disability studies are limited. Carlos Ponce Sanginés and Gregorio Cordero Miranda (1969) interpreted representations of individuals with kyphosis throughout Andean prehistory to trace the origins and reimaginings of the Andean gods Ekeko and Tunupa. A famous bioarchaeological case study of disability focused on the monumental Moche (pre-Inka society) site of Dos Cabezas in the north coast of Peru (ca. 390-645), where Alana Cordy-Collins (2003; Cordy-Collins and Merbs 2008) studied individuals with gigantism and kyphosis who were ritually buried in warrior attire and likely served as spiritual guardians. Recently, Enrico Cioni (2014) used Moche ceramic iconography to analyze how the Moche perceived disability and Rebecca Stone (2017) examined the common Moche ceramic effigy of a shaman with visual impairment. Within Inka studies, cultural constructions of disability are mentioned tangentially (Rowe 1946:304; 1958:512; Rostworowski de Diez Canseco 1988:217; Dean 2001:161-162n17; D'Altroy 2015:295).

Disentangling Spanish Colonial-Era Sources

Most ethnohistorical knowledge of the Inkas is derived from the writings of male Spanish conquistadors, colonial bureaucrats, and priests, all with their own cultural, religious, and gender biases. When constructing an ethnohistoric narrative, one must disentangle these prejudices and look for common threads of information. These colonial narratives become more complex once one recognizes these writers' Indigenous informants. Catherine Julien (2000) suggested that Spanish colonial-era chroniclers created these transcriptions of Inka histories to shape a new order of knowing that reimagined Indigenous memories through European-imposed rules of representation.

Throughout Europe's High Middles Ages (ca. 1000-1250) and Late Middle Ages (ca. 1250-1500), individuals with disabilities were often perceived as lower class and typically did not have access to the same socio-economic networks as "able-bodied" members of society (Metzler 2006; 2013). Many thought that physical and mental differences were caused by bodily sickness, demonic cursing, or were intentional obstacles from God (Stiker 1999; Wheatley 2010; Craig 2013). In the Kingdom of Spain during the 15th and 16th centuries, Catholic religious orders established hospitals for individuals with disabilities and they encouraged pilgrimages for miraculous healing (Flynn 1989). Such worldviews were at odds with Indigenous American belief systems, which were often simplified by Spanish colonizers as demonically influenced (Duviols 1971; Mills 1997; 2013; Puente Luna 2007).

It should be stressed that not all Spanish colonial-era chroniclers were Europeans, as the most valuable cultural lenses were provided by Indigenous Andeans. A prime example of this is the sheer depth of cultural knowledge recorded by Quechua nobleman Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala ([1615] 1980). Another important chronicler is Inka Garcilaso de la Vega ([1609] 1976), an early mestizo writer whose mother Isabel Chimpu Uqllu was a descendant of Inka Emperor Thupa Inka Yupanki. Indigenous voices can be heard in colonial testimonies, which help to disentangle Andean worldviews through personal accounts (e.g., Salomon 1988; Puente Luna 2007; Mumford 2008). Using such a range of historic sources allows for a form of salvage ethnohistory, as we are literally reconstructing a bygone era through post-conquest remembrance and understanding cultural norms through then-contemporary Indigenous Andeans.

The Fourth Lifeway (Cuarta/o Calle)

Quechua nobleman Guaman Poma ([1615] 1980:143, 155, 158) and the Mercedarian friar Martín de Murúa ([1590-1616] 1964:82-83) listed 10 calles, or lifeways, for all female and male Andean subjects of the Inkas. Nine of the lifeways were reserved for non-hank'akuna and categorized based upon specific age periods in an individual's life, with ages for each calle being parallel between genders (Dean 2001) (Table 1). 2 These calles were not chronological, but, as suggested by John Rowe (1958), were ranked upon one's work capacity. The hank'akuna were only given one category that encompassed all ages – the Cuarta/o Calle, or Fourth Lifeway.

The hank'akuna's lack of a lifeway fit is further suggested by the term that hank'a is derived from – hank'ay (n. an imbalance, v. to make unstable). The establishment of a calle for the hank'akuna is a means of forcibly fitting a group with a diverse range of bodily configurations within a socially manicured system of balances. While hank'akuna were specifically categorized based upon their atypical bodyminds, the Inkas' societal expectations of these individuals should not be understood as being fully aligned with modern Western biomedical conceptualizations of disability (e.g., Kasonde-Ng'andu 1999).

| Lifeway (Calle) | Idealized Age | Historic Citation |

|---|---|---|

| First Lifeway (Primera/o Calle) | 33 years 25-50 years | GP*:194[196], 215[217] M**:82-83 |

| Second Lifeway (Segunda/o Calle) | 50/60 years 50-60 years | GP:196[198], 217[219] M:82-83 |

| Third Lifeway (Tercera/o Calle) | 80 years 60+ years | GP:198[200], 219[221] M:82-83 |

| Fourth Lifeway (Cuarta/o Calle) | All hank'akuna All hank'akuna | GP:200[202], 221[223] M:82-83 |

| Fifth Lifeway (Quinta/o Calle) | 18 years 18-25 years | GP:202[204], 223[225] M:82-83 |

| Sixth Lifeway (Sexta/o Calle) | 12 years 12-18 years | GP:204[206], 225[227] M:82-83 |

| Seventh Lifeway (Séptima/o Calle) | 9 years 9-12 years | GP:206[208], 227[229] M:82-83 |

| Eighth Lifeway (Octava/o Calle) | 5 years 5-9 years | GP:208[210], 229[231] M:82-83 |

| Ninth Lifeway (Novena/o Calle) | 1 year Walking-5 years | GP:210[212], 231[233] M:83 |

| Tenth Lifeway (Décima/o Calle) | 1 month Birth-Walking | GP:212[214], 233[235] M:83 |

| *GP = Guaman Poma 1615 | **M = Murúa [1590-1616] 1964 | ||

The Inka Empire strictly controlled marriage practices (Costin 1998; Gose 2000), and the hank'akuna were only allowed to marry somebody of a similar physical condition (Guaman Poma [1615] 1980:152). To this day, many Indigenous communities in the Andes hold the notion that one is not an adult until marriage and childbirth (Rowe 1958; Dean 2001) – with marriage amongst Quechua communities signifying the creation of a totality from two complementary halves, a concept known as yanantin (e.g., Platt 1986). This ability to marry and grow the imperial population via childbirth elevated non-hank'a from the Quinta/o Calle, or Fifth Lifeway, into the Primera/o Calle, or First Lifeway. Being an hank'a, appears to have transcended traditional age categories, although presumably an hank'a also qualified as an adult by marriage. Guaman Poma ([1615] 1980:143, 155, 158) suggested marriages were important in the hopes of multiplying hank'akuna, as specific atypical body configurations were commodified.

The Inkas were very specific as to who qualified for the Fourth Lifeway. Guaman Poma listed a range of physical differences and disabilities, mentioning the preferred Quechua nomenclature and then translating these into colonial-era Spanish. While Guaman Poma and other Spanish colonial-era chroniclers paid the most attention to k'umukuna (individuals with kyphosis) and t'inrikuna (individuals with dwarfism) in their writings, they also wrote about ñawsakuna (individuals with total visual impairment), upakuna (individuals who are non-verbal), and wiñay unquqkuna (individuals with chronic illness). Guaman Poma's terminology for disabilities is corroborated in the first published Quechua-Spanish dictionary by Jesuit priest Diego González Holguín (1608). These Quechua terms for physical disabilities continue in modern Qusqu Runasimi (Cuzco Quechua).

Understanding Tawantinsuyu's Societal Expectations

Hank'akuna were valued for a variety of occupations dependent on their physical state of being and biological sex, although they were excluded from some obligations and statuses (Dean 2001:161-162n17) – such as males serving in the military or females being aqllakuna (sequestered virgins in the religious service of Tawantinsuyu – see Costin 1998; Gose 2000). If an hank'a was able to work, they were commodified to tasks deemed suitable to their respective physical abilities. If an hank'a was unable to labor, they were provided for by the Inka estates and offered a caretaker (Cieza de León [1553] 2005:341; Vega [1609] 1976:217, 242-243; [1609] 1976b:80; Guaman Poma [1615] 1980:143).

Inka leaders valued male hank'akuna as khipukamayuqkuna (khipu readers; a knotted-cord information recording device – see Salomon 2004), labor organizers, and agricultural workers (Guaman Poma [1615] 1980:143). Male k'umukuna were preferred as gatekeepers to royal Inka estates and were highly trusted by Inka elites (Guaman Poma 1615:329[331]). Female hank'akuna could serve as chicha (corn beer) brewers, cooks, farmers, and weavers of fine cloth and high-status clothing, such as chumpi (sashes) and wincha (female headbands) (Guaman Poma [1615] 1980:155, 158). According to Aymara nobleman Pachacuti Yamqui Salcamaygua ([early 17th c.] 1879:277), at the beginning of Tawantinsuyu's expansion (ca. 1438), Emperor Pachakutiq Inka Yupanki permitted hank'akuna subjects to weave fine textiles for the empire. If an hank'a's physical state of being prevented them from serving the mit'a (seasonal labor tax by Tawantinsuyu), then female and male hank'akuna still aided weavers by spinning yarn and creating rope. Cloth was Tawantinsuyu's most culturally esteemed and economically important good (Murra 1962; Costin 1998); the production of fine cloth held great ritual significance and including hank'akuna in its creation further stresses their unique position within society.

Vega ([1609] 1976:236-237) claimed that if festivities were permitted by the Inkas after a "peaceful" acquisition of a new region – typically using persuasion via coerced consent (e.g., Godelier 1978) – the Inkas would invite everyone, including the hank'akuna, to performatively join the state-sponsored celebration to demonstrate that all subjects were a part of the empire. Khipukamayuqkuna (khipu readers) (Collapiña, Supno et al. [1542] 1974:37; Guaman Poma [1615] 1980:135-136) suggested that Wiraqucha Inka – father of Pachakutiq Inka Yupanki – commanded his kurakakuna (local lords) to eat with their families within community plazas that were accessible, particularly for hank'akuna. The Inkas carefully planned plazas to guarantee accessibility for crowds (Gasparini and Margolies 1980); this was a means of guiding local populations into imperially dictated spaces that offered inclusion via coerced collective consent to inculcation of imperial propaganda and religious celebrations (see Ogburn 2004).

Inka royalty preferred to have k'umukuna and t'inrikuna around them in royal spaces, for spiritual protection, as yanakuna (retainers of royal estates or prized imperial servants – see Rowe 1946); sometimes the Inka elites adopted them as their own children (Figure 3) (Guaman Poma [1615] 1980:100, 243; Murúa [1590-1616] 1964:97-98). Guaman Poma ([1615] 1980:143) noted the hank'akuna were valued for serving the gods due to their believed connection to the supernatural. An hank'a could be a high-ranking sorcerer within their community, an oracle for a wak'a (landscape features, objects, and beings that were worshipped – see Mannheim and Salas Carreño 2015), or even revered as a wak'a (Albornoz [1570] 1967:19; Polo de Ondegardo [1571] 1916:114-115; Acosta [1590] 1894:99; Murúa [1590-1616] 1964:97-98). Jesuit missionary Bernabé Cobo ([1653] 1990:161) claimed the Inkas believed Wiraqucha (the Creator God) commanded that hank'akuna be sorcerers.

Prominent Inka hank'akuna were installed as provincial governors or even judges (Guaman Poma [1615] 1980:251). These elite hank'akuna were powerful figures and were well respected in Inka society. When Inka Emperor Wayna Qhapaq ascended to power (ca. 1493), he was quite young and his uncle Wallpaya, who was the Governor of Cuzco (Tawantinsuyu's capital), served as regent. According to some chroniclers (Cabello Balboa [1586] 1951:359; Murúa [1590-1616] 1962:75), Wallpaya was a k'umu who had a fervently loyal following and was venerated by many. Pachacuti Yamqui Salcamaygua ([early 17th c.] 1879:293-296) noted that Wallpaya was fanatically worshipping Inti (the Sun god), Mama Killa (the Moon Goddess), and Ilyap'a (the Lightning and Thunder God), simultaneously trying to sequester their favor by establishing royal estates for each of them. With Wallpaya's ever growing power and his followers rising to the thousands, he nearly incited a coup against his nephew to become emperor until another of Wayna Qhapaq's uncles intervened and mandated Wallpaya's execution. While similar royal power plays are common in Inka history, as throughout the world, such an ability to harness political power, manipulate spiritual realms, and guide followers by an hank'a, regardless of their physical difference, is an important feat to recognize. Wallpaya was not stigmatized for his bodily difference—his charismatic authority was derived from this.

Figure 3. A drawing of a female k'umu (person with kyphosis) within the care of the Inka royal Chuquillanto, attended by guards and servants. This page is from The Getty Manuscript of the Basque friar Martín de Murúa's Historia General del Piru, and the respective Indigenous Andean artist that created this scene was Guaman Poma (Adorno and Boserup 2008:32). Chuquillanto; Unknown; completed in 1616; Ms. Ludwig XIII 16 (83.MP.159), fol. 89. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, CA (digital image courtesy of The Getty's Open Content Program).

The Spanish Extirpation of Idolatry and the Targeting of Hank'akuna

Near Huamachuco in northern Peru, the first Augustinian friars (San Pedro [1560] 1992:23) noted an important k'umu sorcerer that served a wak'a named "Caoquilca," which was a unique stone in the form of a hand. This wak'a possessed its own large house for community festivities. Caoquilca and its dwelling were destroyed by the Spanish and the Augustinians failed to mention what happened to the sorcerer. Spanish targeting of hank'akuna sorcerers became increasingly common throughout the Andes as the Catholic Church's reach grew. Militant approaches to silencing persistent Indigenous religions throughout the Americas were justified by the accusation that these spiritual beliefs were shaped by demonic forces (Mills 2013). Not only were Indigenous religious practices forcibly discouraged, but European colonialism also failed to respect colonized societies' systems of social difference (e.g., Barclay 2017).

Cobo ([1653] 1990:161) accused the Inkas of creating a false spiritual place for the hank'akuna within Andean society. Others, such as the Jesuit missionary Pablo José Arriaga ([1621] 1920:135), thought that Indigenous people with disabilities were spiritually victimized by Andean communities. By the 17th century, such lambasting of spiritually empowered hank'akuna by Catholic agents of the extirpation movement – the Catholic Church's concerted effort to dismantle Indigenous religious practices – was common (Duviols 1971; Mills 1997; Puente Luna 2007). The Spanish tried to rationalize why Indigenous subjects could have physical disabilities, with accusations including coca abuse (Quiroga [1563] 2009:474-475) or even cranial modification practices amongst some ethnic groups (Cobo [1653] 1990:200).

The Spanish actively removed hank'akuna from their esteemed places within their communities and further heightened social hierarchies by relegating them to the lowest rungs of colonial society. Arriaga ([1621] 1920:135) directly commanded that extirpators should view an Indigenous Andean's disability as being a possible clue to their role as a sorcerer – a viewpoint that the priest Rodrigo Hernández Príncipe ([1622] 1923:45), when writing to the then Archbishop of Lima, Bartolomé Lobo Guerrero, shared as well. In 1649, Pedro de Villagómez ([1649] 1919:224), who was leading a revitalization of the extirpation movement as the head of the Metropolitan See of Lima, copied Arriaga's fact verbatim in his extirpation instructions.

In Acas of Peru, a man that locals referred to as Alonso Chaupis el Ciego ("the Blind" in Spanish) was a prominent sorcerer with visual impairment – who we know because of a series of testimonies that were made about him in 1657 by his own community at the pressure of Catholic extirpators (e.g., Poma y Alto Caldea [1657] 1986; Hacasmalqui [1657] 1986). Alonso Chaupis officiated curing ceremonies that involved ritual sacrifice of llamas and guinea pigs in Acas and adjacent villages. He was also a caretaker of the dead – local ancestral malquikuna (mummies) and their machaykuna (cave tombs) within the community. An important fact to consider is how even the malqui of an hank'a could be revered. Arriaga ([1621] 1920:99-100) noted that he personally encountered a machay of malquikuna in Colquioc, Peru; three of the more prominent malquikuna displayed pronounced gigantism and had atypical heads. Unfortunately, Arriaga coerced the community to relinquish their malquikuna and he promptly burned their ancestors to prevent a return to perceived pagan ways.

The Catholic Church would on occasion offer employment to hank'akuna, typically incorporating them as sacristans and sextons – preparers of ceremonies and caretakers of their local churches and parishes (Guaman Poma [1615] 1980:97, 115, 149). While an hank'a's physical difference was their source of power in Inka society, under the Spanish such physical states of being often made them ineligible from holding power. But even when placed into positions of religious subservience, an hank'a could still be revered more than the Church would have liked. In 1662 in Otec, Peru, there was a report (Causa criminal [1662] 1991:77-78) of an individual who had a mobility impairment and was referred to in testimony simply as Yndio Cojo ("Crippled Indian" in colonial Spanish); however, the local community called him el Doctor. By day, he served as a potter for a local priest; by night, he was legendary for being paraded on a litter and performing spiritual healing ceremonies.

The Calle Continues: Modern Hank'akuna

While Indigenous communities throughout the Andes, including Cuzco, had their hank'akuna stripped of political powers and social roles with the tightening grip of Spanish colonialism, there are still places where inklings of hank'a tradition continue. In the Aymara community of Acora, Peru in the early-20th century, Horacio Urteaga (1914:73-75) observed that community members with visual impairments (juykhu in Aymara) were valued on the Día de los Fieles Difuntos (All Souls' Day – November 2nd) for being able to connect community members with deceased relatives. It was believed that while they cannot see in the physical world, they can see into the afterlife.

While conducting fieldwork in the Quechua village of Pocona, Bolivia in 1978, Diane Perlov (2009:69; Personal Communication, November 17, 2014) studied chicheras (chicha brewers), a female engendered and socially prestigious occupation. Perlov related a then-recent incident of a male k'umu who was about to be hanged for an undisclosed offense. At the last minute, a chichera arbitrated and offered to adopt him as a brewer. Such an inclusion of a male in this activity was not the social norm, but his physical difference seemed to allow a permitted pathway to redemption. K'umukuna were long ago valued as chicha brewers.

Ina Rösing (1999:34-35) reported that in the Quechua village of Amarete, Bolivia, specific physical disabilities are linked to community vocations. For example, watapurichiqkuna (ritualists) can perform specific functions dependent on their physical disability. If one is unable to use their left hand or arm, or has a developmental disability associated with it, then they are valued for black magic, which are cursing rituals. Conversely, if the same applies to one's right hand or arm, they are valued for white magic, which are healing rituals.

Conclusion

Under Tawantinsuyu, the respective role that an hank'a played within society was directly related to their physical difference, thus it was what made them unique that imbued them with their power. The Inkas consciously developed social traditions that simultaneously recognized, fetishized, and valued such differences. Unfortunately, Spanish colonialism forcibly altered many Andean communities' social systems of inclusivity. However, cultural resilience can be seen with the survival of similar traditions amongst some modern Indigenous Andean communities that still actively celebrate unique conceptions of bodily difference and bodily configuration.

References Cited

- Acosta, José de. [1590] 1894. Historia natural y moral de las Indias. Vols. 1-2. Madrid: Ramón Anglés.

- Adorno, Rolena, and Ivan Boserup. 2008. "The Making of Murúa's Historia General del Piru." Pp. 7-76 in The Getty Murúa: Essays on the Making of Martín de Murúa's "Historia General del Piru," edited by T. Cummins and B. Anderson. Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute.

- Albornoz, Cristóbal de. [1570] 1967. "Instrucción para descubrir todas las guacas del Pirú y sus camayos y haziendas," edited by P. Duviols. Journal de la Société des Américanistes 55(1):17-39.

- Arriaga, Pablo José [1621] 1920. La extirpación de la idolatría en el Peru, edited by H. H. Urteaga Lima: Sanmartí y Ca.

- Bacon, Wendy J. 2007. "The Dwarf Motif in Classic Maya Monumental Iconography: A Spatial Analysis." Ph.D. dissertation, Department of Anthropology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

- Barclay, Jennifer L. 2017. "Differently Abled: Africanisms, Disability, and Power in the Age of Transatlantic Slavery." Pp. 77-94 in Bioarchaeology of Impairment and Disability: Theoretical, Ethnohistorical, and Methodological Perspectives, edited by J. F. Byrnes and J. L. Muller. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-56949-9_5

- Burch, Susan. 2021. Committed: Remembering Native Kinship In and Beyond Institutions. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press.

- Cabello Balboa, Miguel. [1586] 1951. Miscelánea antártica: una historia del Perú antiguo. Lima: Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, Instituto de Etnología y Arqueología.

- Causa criminal. [1662] 1991. "Causa criminal contra María Susa Ayala, mercachifle, acusada de inquietar a los hombres y comerciar con tierra, agua y hierbas que tienen virtud de ventura…" Pp. 73-129 in Amancebados, hechiceros y rebeldes: Chancay, siglo XVII, edited by A. Sánchez. Cuzco: Centro de Estudios Regionales Andinos Bartolomé de Las Casas.

- Cieza de León, Pedro de. [1553] 2005. Crónica del Perú: El Señorio de los Incas, edited by F. Pease G.Y. Caracas: Biblioteca Ayacucho.

- Cioni, Enrico. 2014. "Who were the Moche Disabled? Exploring Past Perceptions of Disability through Iconography." Thesis, Emmanuel College, University of Cambridge.

- Cobo, Bernabé. [1653] 1990. Inca Religion and Customs, translated by R. Hamilton. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Coggins, Clemency Chase. 1994. "Man, Woman and Dwarf." Pp. 28-72 in Memorias del Primer Congreso Internacional de Mayistas. Vol. 3, Conferencias plenarias, arte prehispánico, historia, religión. Mexico City: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Mexico.

- Collapiña, Supno, and other Khipukamayuqkuna. [1542] 1974. Relación de la descendencia, gobierno, y conquista de los Incas, edited by J. J. Vega. Lima: Editorial Jurídica.

- Cordy-Collins, Alana. 2003. "Five Cases of Prehistoric Peruvian Gigantism." Pp. 115-120 in Mummies in a New Millennium: Proceedings of the 4th World Congress on Mummy Studies, Nuuk, Greenland, September 4th to 10th, 2001, edited by N. Lynnerup, C. Andreasen, and J. Berglund. Copenhagen: Greenland National Museum and Archives and Danish Polar Center.

- Costin, Cathy Lynne. 1998. "Housewives, Chosen Women, Skilled Men: Cloth Production and Social Identity in the Late Prehispanic Andes." Pp. 123-141 in Craft and Social Identity, edited by C. L. Costin. Washington, D.C.: American Anthropological Association. https://doi.org/10.1525/ap3a.1998.8.1.123

- Craig, Leigh Ann. 2013. "The Spirit of Madness: Uncertainty, Diagnosis, and the Restoration of Sanity in the Miracles of Henry VI." The Journal of Medieval Religious Cultures 39(1):60-93. https://doi.org/10.5325/jmedirelicult.39.1.0060

- D'Altroy, Terence N. 2015. The Incas. 2nd ed. Malden: Blackwell Publishers.

- Dean, Carolyn. 2001. "Andean Androgyny and the Making of Men." Pp. 143-182 in Gender in Pre-Hispanic America, edited by C. F. Klein and J. Quilter. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks.

- Devlieger, Patrick J. 1999. "Developing Local Concepts of Disability: Cultural Theory and Research Projects." Pp. 297-302 in Disability in Different Cultures: Reflections on Local Concepts, edited by B. Holzer, A. Vreede, and G. Weigt. Bielefeld, Germany: Transcript Verlag. https://doi.org/10.14361/9783839400401-025

- Duviols, Pierre. 1971. La lutte contre les religions autochtones dans le Pérou colonial; l'extirpation de l'idolatrie entre 1532 et 1660. Lima: Institut Français d'Études Andines.

- Flynn, Maureen. 1989. Sacred Charity: Confraternities and Social Welfare in Spain, 1400-1700. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-09043-3

- Gasparini, Graziano and Luise Margolies. 1980. Inca Architecture, translated by P. J. Lyon. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Gassaway, William T. 2017. "Divining Disability: Criticism as Diagnosis in Mesoamerican Art History." Pp. 60-81 in Disability and Art History, edited by A. Millett-Gallant and E. Howie. New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315440002-12

- Godelier, Maurice. 1978. "Infrastructures, Societies, and History." Current Anthropology 19(4):763-771. https://doi.org/10.1086/202197

- González Holguín, Diego. 1608. Vocabulario de la lengua general de todo el Peru llamada lengua Qquichua, o del Inca. Lima: Francisco del Canto.

- Gose, Peter. 2000. "The State as a Chosen Woman: Brideservice and the Feeding of Tributaries in the Inka Empire." American Anthropologist 102(1):84-97. https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.2000.102.1.84

- Guaman Poma de Ayala, Felipe. 1615. El primer nueva corónica i buen gobierno. Available from The Guaman Poma Website of the Digital Research Center of Det Kongelige Bibliotek, Copenhagen, Denmark. Retrieved Oct. 31, 2012 (http://www.kb.dk/permalink/2006/poma/info/en/frontpage.htm). [1615] 1980. Nueva corónica y buen gobierno. Vols. 1-2, edited by F. Pease G.Y. Caracas: Biblioteca Ayacucho.

- Hacasmalqui, Christobal. [1657] 1986. "El testimonio de Christobal Hacasmalqui." Pp. 165-172 in Cultura andina y represión: Procesos y visitas de idolatrías y hechicerías: Cajatambo, siglo XVII, edited by P. Duviols. Cuzco: Centro de Estudios Rurales Andinos Bartolomé de las Casas.

- Hechler, Ryan Scott, and William S. Pratt. 2015. "Representing Difference in the Pre-Columbian Andes: An Iconographic Examination of Physical Disability." Presented at the Society for American Archaeology 80th Annual Meeting, April 18, San Francisco.

- Hernández Príncipe, Rodrigo. [1622] 1923. "Mitología andina." Inca 1:25-68.

- Hubert, Jane. 2000. "The Complexity of Boundedness and Exclusion." Pp. 1-8 in Madness, Disability and Social Exclusion: The Archaeology and Anthropology of 'Difference,' edited by J. Hubert. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315812151

- Joe, Jennie Rose. 1980. "Disabled Children in Navajo Society." PhD dissertation, Department of Anthropology, University of California, Berkeley.

- Julien, Catherine J. 2000. Reading Inca History. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt20q1xg1

- Kasonde-Ng'andu, Sophie. 1999. "Bio-Medical versus Indigenous Approaches to Disability." Pp. 114-121 in Disability in Different Cultures: Reflections on Local Concepts, edited by B. Holzer, A. Vreede, and G. Weigt. Bielefeld, Germany: Transcript Verlag. https://doi.org/10.14361/9783839400401-007

- Mannheim, Bruce, and Guillermo Salas Carreño. 2015. Wak'as: Entifications of the Andean Sacred. Pp. 47-72 in The Archaeology of Wak'as: Explorations of the Sacred in the Pre-Columbian Andes, edited by T. L. Bray. Boulder: University Press of Colorado. https://doi.org/10.5876/9781607323181.c003

- Metzler, Irina. 2006. Disability in Medieval Europe: Thinking About Physical Impairment during the High Middle Ages, c. 1100-1400. New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203016060 2013. A Social History of Disability in the Middle Ages: Cultural Considerations of Physical Impairment. New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203371169

- Miller, Virginia E. 1985. "The Dwarf Motif in Classic Maya Art." Pp. 141-153 in Fourth Palenque Round Table, 1980, edited by M. G. Robertson and E. P. Benson. San Francisco: Pre-Columbian Art Research Institute.

- Mills, Kenneth R. 1997. Idolatry and Its Enemies: Colonial Andean Religion and Extirpation, 1640-1750. Princeton: Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780691187334 2013. "Demonios Within and Without: Hieronymites and the Devil in the Early Modern Hispanic World." Pp. 40-68 in Angels, Demons and the New World, edited by F. Cervantes and A. Redden. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139023870.004

- Mumford, Jeremy Ravi. 2008. "Litigation as Ethnography in Sixteenth-Century Peru: Polo de Ondegardo and the Mitimaes." Hispanic American Historical Review 88(1):5-40. https://doi.org/10.1215/00182168-2007-077

- Murra, John V. 1962. "Cloth and Its Functions in the Inca State." American Anthropologist 64(4):710-728. https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.1962.64.4.02a00020

- Murúa, Martín de. [1590-1616] 1962-64. Historia general del Perú, origen y descendencia de los Incas. Vols. 1-2, edited by M. Ballesteros Gaibrois. Madrid: Bibliotheca Americana Vetus.

- Mutua, N. Kagendo. 2001. "The Semiotics of Accessibility and the Cultural Construction of Disability." Pp. 103-116 in Semiotics & Dis/ability, edited by L. J. Rogers and B. B. Swadener. Albany: State University of New York Press.

- O'Brien, Jean M. 2017. "Historical Sources and Methods in Indigenous Studies: Touching on the Past, Looking to the Future." Pp. 15-22 in Sources and Methods in Indigenous Studies, edited by C. Andersen and J. M. O'Brien. New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315528854

- Ogburn, Dennis. 2004. "Dynamic Display, Propaganda and the Reinforcement of Provincial Power in the Inca Empire." Archaeological Papers of the American Anthropological Association 14(1):225-239. https://doi.org/10.1525/ap3a.2004.14.225

- Pachacuti Yamqui Salcamaygua, Juan de Santa Cruz. [early 17th c.] 1879. "Relación de antigüedades deste reyno del Pirú." Pp. 229-328 in Tres Relaciones de Antigüedades Peruanas, edited by M. Jiménez de la Espada. Madrid: Imprenta de M. Tello.

- Perlov, Diane C. 2009. "Working through Daughters: Strategies for Gaining and Maintaining Social Power among the Chicheras of Highland Bolivia." Pp. 49-74 in Drink, Power, and Society in the Andes, edited by J. Jennings and B. J. Bowser. Gainesville: University Press of Florida. https://doi.org/10.5744/florida/9780813033068.003.0003

- Platt, Tristan. 1986. "Mirrors and Maize: The Concept of Yanantin among the Macha of Bolivia." Pp. 228-259 in Anthropological History of Andean Polities, edited by J. V. Murra, N. Wachtel, and J. Revel. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511753091.019

- Polo de Ondegardo, Juan. [1571] 1916. "Relación de los fundamentos acerca del notable daño que resulta de no guardar a los Indios sus fueros." Pp. 45-188 in Informaciones acerca de la religión y gobierno de los Incas. Vol. 1, edited by H. H. Urteaga. Lima: Sanmartí y Ca.

- Poma y Altas Caldeas, Francisco. [1657] 1986. "El testimonio de Francisco Poma y Altas Caldeas." Pp. 182-191 in Cultura andina y represión: Procesos y visitas de idolatrías y hechicerías: Cajatambo, siglo XVII, edited by P. Duviols. Cuzco: Centro de Estudios Rurales Andinos Bartolomé de las Casas.

- Ponce, Jocelyne M., and Ryan Scott Hechler. 2016. "Revering Difference: Understanding Physical "Disability" in Pre-Columbian Mesoamerica and the Social Transition to Spanish Rule." Presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Society for Ethnohistory, November 12, Nashville.

- Ponce Sanginés, Carlos, and Gregorio Cordero Miranda. 1969. Tunupa y Ekako: Estudio arqueológico acerca de las efigies pre-colombinas de dorso adunco. La Paz: Academia Nacional de Ciencias de Bolivia.

- Prager, Christian. 2002. "Enanismo y gibosidad: Las personas afectadas y su identidad en la sociedad Maya del tiempo prehispánico." Pp. 35-67 in La organización social entre los Maya prehispánicos, coloniales y modernos, edited by V. Tiesler Blos, R. Cobos, and M. Greene Robertson. Mexico City: Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia.

- Puente Luna, José Carlos de la. 2007. Los curacas hechiceros de Jauja: Batallas mágicas y legales en el Perú colonial. Lima: Fondo Editorial.

- Quiroga, Pedro de. [1563] 2009. "Edición de coloquios de la verdad de Pedro de Quiroga." Pp. 329-530 in El indio divido: Fracturas de conciencia en el Perú colonial, edited by A. Vian Herrero. Madrid: Iberoamericana. https://doi.org/10.31819/9783954871711

- Rösing, Ina. 1999. "Stigma or Sacredness: Notes on Dealing with Disabilities in an Andean Culture." Pp. 27-43 in Disability in Different Cultures: Reflections on Local Concepts, edited by B. Holzer, A. Vreede, and G. Weigt. Bielefeld, Germany: Transcript Verlag. https://doi.org/10.14361/9783839400401-001

- Rostworowski de Diez Canseco, María. 1988. Historia del Tahuantinsuyu. Lima: Instituto de Estudios Peruanos.

- Rowe, John H. 1946. "Inca Culture at the Time of the Spanish Conquest." Pp. 183-330 in Handbook of South American Indians. Vol. 2, The Andean Civilizations, edited by J. Steward. Washington, D.C.: Bureau of American Ethnology. 1958. "The Age Grades of the Inca Census." Pp. 499-522 in Miscelánea Paul Rivet Octogenario Dictata. Vol. 2. Mexico City: Instituto de Historia de la Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

- Salomon, Frank L. 1988. "Indian Women of Early Colonial Quito as Seen Through Their Testaments." The Americas (44)3:325-341. https://doi.org/10.2307/1006910 2004. The Cord Keepers: Khipus and Cultural Life in a Peruvian Village. Durham: Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822386179

- San Pedro, Juan de. [1560] 1992. Relación de la religión y ritos del Perú hecha por los padres agustinos, edited by L. Castro de Trelles. Lima: Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú – Fondo Editorial.

- Senier, Siobhan. 2017. "Blind Indians: Káteri Tekakwí:tha and Joseph Amos's Visions of Indigenous Resurgence." Pp. 269-289 in Disability Studies and the Environmental Humanities: Toward an Eco-Crip Theory, edited by S. J. Ray and J. Sibara. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt1p6jht5.12

- Stiker, Henri-Jacques. 1999. A History of Disability, translated by W. Sayers. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.15952

- Stoler, Ann Laura. 2009. Along the Archival Grain: Epistemic Anxieties and Colonial Common Sense. Princeton: Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400835478

- Stone, Rebecca Rollins. 2017. "Nothing is Missing: Spiritual Elevation of a Visually Impaired Moche Shaman." Pp. 47-59 in Disability and Art History, edited by A. Millett-Gallant and E. Howie. New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315440002-11

- Strong, Pauline Turner. 2017. "History, Anthropology, Indigenous Studies." Pp. 31-40 in Sources and Methods in Indigenous Studies, edited by C. Andersen and J. M. O'Brien. New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315528854

- Urteaga, Horacio H. 1914. El Perú: Bocetos Históricos. Vol. 1. Lima: E. Rosay.

- Vega, Inka Garcilaso de la. [1609] 1976. Comentarios reales de los Incas. Vols. 1-2, edited by A. Miró Quesada. Caracas: Biblioteca Ayacucho.

- Villagómez, Pedro de. [1649] 1919. Exortaciones e instrucción acerca de las idolatrías de los indios del arzobispado de Lima, edited by H. H. Urteaga. Lima: Sanmartí y Ca.

- Wheatley, Edward. 2010. Stumbling Blocks Before the Blind: Medieval Constructions of Disability. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.915892

Endnotes

-

I am forever grateful to my Qusqu Runasimi instructors Regina Tupacyupanqui Arredondo, who started my linguistic journey in Cuzco, Peru, and to Alicia Galdós Bejar, who continued it. I presented an early version of this paper at the Northeast Conference on Andean Archaeology and Ethnohistory on October 19, 2014, at the University of Vermont in Burlington; I am appreciative of the feedback I received from colleagues there. I am much obliged to Susan Burch, Ella Callow, and Juliet Larkin-Gilmore for their support throughout this article's publication process.

Return to Text -

Calles literally means "streets" or "pathways" in Spanish. Peculiarly, Guaman Poma and Murúa used a Spanish word instead of a Quechua term, although these chroniclers were otherwise verbose about Quechua terminology.

Return to Text