This study considers the life courses of young men and women with and without disabilities in the Sundsvall region of Sweden during the nineteenth century. It aims to ascertain how disability and gender shaped their involvement in work and their experience of family in order to assess the extent of their social inclusion. Through the use of Swedish parish registers digitized by the Demographic Data Base, Umeå University, we examine 8,874 individuals observed from 15 to 33 years of age to investigate whether obtaining a job, getting married and having children were less frequent events for people with disabilities. Our results reveal that this was the case and particularly for those with mental disabilities, even if having an impairment did not wholly prevent people from finding a job. However, their work did not represent the key to family formation and for the women it implied a higher rate of illegitimacy. We argue that the lower level of inclusion in work and family was not solely the outcome of the impairment itself, but differed in relation to the particular attitudes towards men and women with disabilities within the labour market and society more generally in this particular context.

1 INTRODUCTION

1.1 BACKGROUND

Whether in relation to the past or present-day society, there are few studies investigating how individuals' lives develop with regard to work and family if disability was or is present in life. This analysis contributes historical knowledge on this issue by uncovering the life trajectories of thousands of people living in Sweden some 150–200 years ago. Recent studies of the contemporary situation have found that disabilities make individuals more disadvantaged in the labour market than the "able" majority (Arvidsson, Widén & Tideman, 2015; Barnes & Mercer, 2005; Kavanagh et. al, 2013; National Board of Health and Welfare Report, 2009; Reine, Palmer & Sonnander, 2016; Tøssebro & Kittelsaa, 2004). In turn, this disadvantage may explain why disabilities tend to make people more likely to live without a partner or a family on their own (Franklin, 1977; Sainsbury & Lloyd-Evans, 1986; Schur et al., 2013), as uncertain resources make individuals less attractive in the partner market. Disability scholars argue that the impairment itself cannot explain these patterns of inequality. Environmental factors must be considered and not only in terms of welfare provisions, as prevailing perceptions about normalcy in the surrounding society tend to promote marginalization that further impedes the possibilities of people with disabilities finding a job or a partner (Barnes & Mercer, 2005, 2010; Oliver, 1996; Priestley, 2003; Siminski, 2003). As for past societies, information on the working and social lives of people with disabilities is scarce due to deficient or mediated documentation in historical sources. Scholars in disability history have primarily analysed records from institutions to which some people labelled disabled were admitted, or poor relief and crime records in which some disabled people crop up as a result of the economic difficulties they faced (Engberg, 2005; Vikström, 2006; Turner, 2012). Another, smaller group of disabled individuals have left better primary source materials because they led exceptional lives or enjoyed public careers that were sufficiently notable to have been documented (Nielsen, 2001). Such problems with the primary source material jeopardise historians' chances of constructing histories that recognise and account for the diverse experiences of people with disabilities in the past.

Finding a job, getting married and having children were expected and common events as young people in the past transitioned into adult life. While it is difficult to know the extent to which individual people's lives approximated this idealised pathway generally, it is an even greater challenge ascertaining whether people with disabilities did so. Two individuals with disabilities according to the parish registers for the Sundsvall region, Sweden, in the nineteenth century exemplify that a life with disabilities could develop in quite different directions. Both were born in 1820. When Nils Jonas was four years old, the parish registers reported him as being weak-sighted, while they recorded Anna Brita to be deaf when she was eleven years old. In 1837, she was noted as a 17-year old maidservant (piga). In 1846, and at the age of 26, Anna Brita married a crofter, and in the following year she gave birth to their first baby, a girl. While her hearing impairment did not seem to stop her from finding work and forming a family, Nils Jonas did not experience all these events during the time we follow him (i.e. until the age of 33). We know he was a farmhand from the age of 18, but, by the time he was 33 years old, he was still recorded as an unmarried farmhand.

1.2 AIMS

With the different experiences of Anna Brita and Nils Jonas in mind, our aim is to clarify how disabilities affected the life course of people using Swedish parish registers. We compare a series of essential events in their lives with a group of non-disabled individuals, all of whom resided in the nineteenth-century Sundsvall region of Sweden. The latter cohort work as a control group that helps make clear whether and to what extent getting a job, marrying a spouse and becoming a parent were less common events among individuals with disabilities. The acquisition of a job is of primary interest to us, while we examine the other two events to assess the role of having an occupation for marriage and family formation. To differentiate the individuals' life courses, we investigate if the occurrence and timing of these events varied by gender and disability, and also with regard to different types of disabilities.

2 THEORETICAL CONSIDERATIONS AND PREVIOUS RESEARCH

2.1 THEORETICAL NOTES ASSOCIATED WITH THE LIFE COURSE

The life course approach has some theoretical implications of importance to our study and it has governed the choice of method as explained below (Section 3). This approach has attracted an extensive cross-disciplinary interest (Giele & Elder, 1998; Kok, 2007), in addition to attention from disability scholars (Jeppsson-Grassman & Whitaker, 2013; Priestley, 2003; Sandvin, 2003). This is because it conceptualises the course of life as shaped not only by the identities of the individuals and their decision-making but also by the opportunities, values and norms of the society that work to influence the choices people make across their lifetimes. As people's life course is the outcome of both their individual agency and structural circumstances, it brings each of the two models debated within disability research to the fore. The social model has come to move the focus from the person or the impairment per se (i.e. the individual or medical model) to gain a social understanding of disability, focusing on the limitations or barriers placed in the way of disabled people's full participation in society (Oliver, 1996; Longmore & Umansky, 2001).

According to its proponents, the life course reflects humans' living conditions from cradle to grave, their constraints and possibilities in society (Giele & Elder, 1998; Elder, Kirkpatrick Johnson & Crosnoe, 2004). It involves a line of development that includes phases, such as childhood, adolescence, adulthood and parenthood, and old age, that impact on individuals' status, behaviour, identity, social activities and rights in society. Getting a job, marrying or having a child exemplify life events that affect this line of development. However, having disabilities may jeopardise one's chances to take the course of life one would otherwise have taken or may postpone certain life events, which makes some scholars distinguish between "pathways" and "trajectories" (Kok, 2007). The former prescribes the "appropriate" life course, for instance, the age or timing to take up a job and marry, and may suggest the preferable order of certain events, such as that children should be born within marriage, and not before or beyond marital unions. Pathways thus refer to standardised patterns of human behaviours perceived as "normal" by society at a given time, whereas trajectories show the actual life courses or behaviour of individuals. To gain information on how disabilities affected human life historically, our study investigates life trajectories making use of demographic data on individuals with and without disabilities from the parish registers. We do that by focusing on a transitional phase of young adulthood (between 15 and 33 years of age) when certain crucial demographic events, such as getting the first job, marrying for the first time and giving birth to the first child, tend to occur. The age of 33 was chosen to ensure comparability across the whole period and to ensure the selection of a sufficiently large number of cases to make comparison meaningful.

In both disability studies and disability history, life course analyses are few in number, and even more rare with regard to the quantitative examination of disability. Even though we conduct such an examination to ascertain how life developed in the past among a comparatively large quantity of people, we cannot tell whether their trajectories were primarily the outcome of the individual impairments or rather were shaped by physical obstacles or intolerant attitudes associated with the specific environment. Further, life course scholars argue that there are more aspects to consider in relation the life-span development of individuals, the timing of events and the social ties that shape people's lives (Kok, 2007). Our approach to the life course involves the study of individuals with disabilities from adolescent years (age 15 or before) to see how disabilities influenced the three events of job, marriage and parenthood, and their occurrence and timing up to the age of 33. Our results also reflect how their life courses interlinked with others by their involvement in the labour market (i.e. employers) and in the marriage market (i.e. spouses). Theoretically, we conceive of access to the labour market and family formation as indicative of people's social inclusion.

2.2 THE HISTORICAL CONTEXT AND DISABILITY HISTORY

Disabled or not, young individuals in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Western Europe, particularly in countries such as Sweden where the processes of urbanization and industrialization moved at a slower pace than in other countries, were required to spend a few years of their young lives as servants before progressing to other occupations. This meant that the majority of adolescents, who originated from farming families or the lower socio-economic strata, sought employment as maidservants, farmhands, servants or apprentices in households other than their parents' (Bras, Liefbroer & Elzinga, 2010; Dribe, 2000; Hajnal, 1962; Lundh, 1999, 2003). In Sweden, they usually did so after having passed confirmation around the age of 15 or 16 years (Jacobsson, 2000). The servant system had a profound influence on the marriage patterns resulting in rather high ages at first marriage, as it took time for the future couple to gather the material resources through work to afford an independent household (Hajnal, 1965; Whittle, 2005). Men in nineteenth-century Sweden married at the average age of about 27 and women at 25 (Harnesk, 1990; Gaunt 1983; Lundh, 1997; Vikström, 2003).

Disability may have constituted a direct obstacle for people if the impairment restricted their ability to perform work or establish social relationships with employers or a spouse. This would cut their opportunities in both the labour and marriage markets, especially for men since their gender role posited them as "breadwinners" expected to support themselves and their families (Horrell & Humphries, 1997; Janssens, 1998). However, historical research suggests that disabled people confronted obstacles in life indirectly, not as an immediate consequence of their impairments but more due to discriminatory attitudes towards their disabilities (Borsay, 2005; Jaeger & Bowman, 2005; Kudlick, 2003, 2008; Turner & Stagg, 2006). Yet, impairment did not allow disabled people to escape the social norms and expectations in relation to labour and self-subsistence. In relation to nineteenth-century Scotland, when entitlement to any economic support from society was meagre, Hutchison (2007) concludes that a job and an income was not impossible for disabled persons to find and key for their chances of finding a spouse. On the other hand, other studies indicate that mechanization during industrialization promoted the exclusion of disabled people from labour and society, since factory jobs replaced handicraft and agricultural labour, and disabled people were considered less able to cope with these new industrial tasks (Barnes & Mercer, 2010; Oliver, 1990). Correspondingly, even though the establishment of institutions increased in the nineteenth century (Foucault, 1965), not all persons with disabilities were admitted to them nor could authorities afford to admit them into such institutions. The latter were aware that a job would make disabled persons become productive citizens and thus less of a burden to society (Bengtsson, 2012; Borsay, 2005; Förhammar, 1991). The establishment of special schools for children with sensory or physical impairments was yet another means to help them become productive citizens in adult life through work. However, such educational institutions were few in number in nineteenth-century Sweden (Förhammar & Nelson, 2004; Olsson, 2010).

Apart from this broader context and these particular historical developments, Swedish law also worked to enforce people's moral obligation to work by regulating the relationship between the employed person and his/her employee. The Servant and Master Act (tjänstehjonsstadgan) was in effect from 1664 until 1926 and stipulated that citizens who were not self-employed or did not live off some property or gained support from relatives, were required to find subsistence through employment to enjoy their civil rights in society. Historians argue that the intention with this legislation was to supply employers' call for a workforce and make people work to cut local authorities' costs in terms of poor relief (Harnesk, 1990; Petersson, 1983). While many disabled people were required by this piece of legislation to work to support themselves, some did nevertheless succeed in gaining relief and they have been subject to historical research which provides some insights into their living conditions (Engberg, 2005; Vikström, 2006; Turner, 2012).

The various issues that arise with primary source material when undertaking research on individuals with disabilities in history suggest why studies incorporating life course perspectives are rare, but a few historians have attempted to overcome these difficulties. Olsson (1999) makes use of parish registers to follow some 400 individuals with disabilities over their lifetimes in the Swedish town of Linköping in the nineteenth century. Men primarily worked as unskilled labourers or craftsmen or farmhands, and women as maidservants or seamstresses. Olsson further finds that about 25% of them married, and all these individuals held jobs. She recognises work as key to marriage, showing that they could support their spouse and future children without rendering any cost to society. However, as Olsson does not conduct comparisons with non-disabled people, it is difficult to assess the extent to which disability limited individuals' opportunities to work and to start a family. Such a comparison is present in the thesis of Sofie De Veirman (2015), who makes quantitative life course analyses of people with auditory impairment and their hearing siblings in Flanders before and during industrialization. This comparison leads De Veirman to conclude that hearing impairments impeded the employment and marriage patterns of hearing impaired people, particularly among the men. Similarly, in his thesis on Revolutionary War veterans in the USA, Daniel Blackie (2010) examines the experiences of some 300 men, of whom about 150 had disabilities. He contends there were similarities between these men regarding their post-war working and family lives. Our own life course studies show that disability decreased both individuals' survival chances and marital prospects, as a possible consequence of disadvantaged opportunities in the labour market (Haage, 2017; Haage, Häggström Lundevaller & Vikström, 2016; Haage, Vikström & Häggström Lundevaller, 2017; De Veirman, Haage & Vikström, 2016).

3 AREA, DATA AND METHODS

3.1 THE AREA AND DIGITIZED PARISH REGISTERS

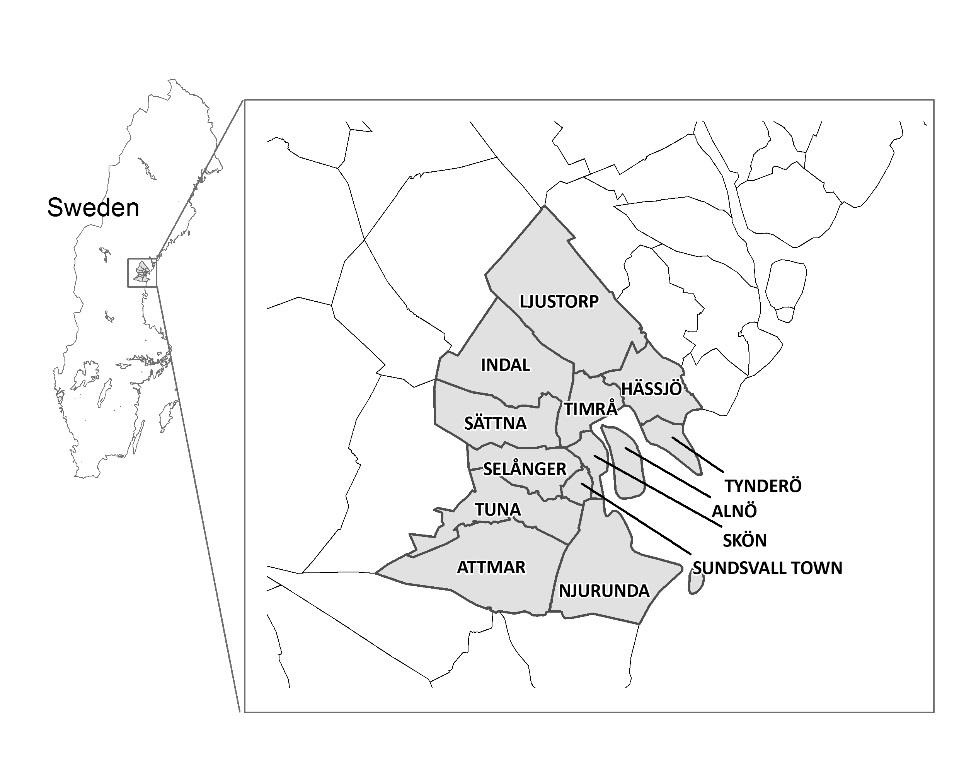

The Sundsvall region (Figure 1) is representative of the demographic and economic structures found elsewhere in nineteenth-century Sweden and north-western Europe. The majority of population depended on agricultural production until the middle of the century but, in four parishes (Alnö, Skön, Njurunda and Timrå), the demographic and socio-economic structure came to change from the 1860s, as economic activity and the labour market became increasingly based on the sawmill industry. The stimulus given to business and commerce were most evident in the town of Sundsvall, the only significant urban community in the region. While the mortality decline of the nineteenth century served to bring about a natural increase in population, the sawmill industry also exerted a pull on migrants which added to the population growth (Bergman, 2010; Edvinsson, 1992; Vikström, 2003). While there were 18,793 inhabitants in the Sundsvall region in 1840, this number had increased to 46,418 in 1880 (Alm Stenflo, 1994). This particular setting, and the existence of digitized parish registers, make the Sundsvall region a unique "historical laboratory" for our analysis.

Apart our own recent studies, this region has not yet been subject to disability history research but has been the object of demographic studies on socio-economic vulnerability in industrial society. A few of these studies consider how norms about labour and marriage in contemporary literature and legislation were reflected in people's lives as recorded in the parish registers. For instance, the increase of migrants and seasonal labour in the sawmills, which was more difficult to control for authorities and more insecure for those employed accordingly, worried social and political elites during the latter part of the century (Bergman, 2010; Vikström, 2003), as did illegitimacy and crime (Brändström, 1999; Vikström, 2008, 2011). These phenomena were viewed as moral threats to the social order, and labour and marriage were highly valued to safeguard the reproduction of families and communities, partly in the hope that such values would decrease the costs incurred because of unemployment, crime and illegitimacy. Studies based on the parish registers for the Sundsvall region provide a complex picture in which a range of attitudes and experiences are evident. On the one hand, some individuals were stigmatized by continued unemployment or recidivism or by never marrying, or, in the case of women, through giving birth to illegitimate children. On the other hand, surprisingly many of these groups of people took up work and married later in life and did not seem to suffer an untimely death due to poor or unhealthy living conditions. The outcome of the analysis below will suggest whether such tolerant attitudes included people who may have looked or behaved differently because of their impairments.

Source: Demographic Data Base, Umeå University

Figure 1. Map of Sweden and the Sundsvall region showing the parishes included in the study.

The Demographic Data Base (DDB) at Umeå University, Sweden, has digitized the parish registers of the Sundsvall region. They consist of original records for parishioners' births, baptisms, marriages, out- or in-migration, deaths and burials, the catechetical examination registers, and provide notes on occupations and impairments. Being linked on an individual level, the DDB's parish registers yield a demographic description of each person and the timing of essential events in their lives, such as the first employment, marriage, parenthood, migration or death (Vikström, Brändström & Edvinsson, 2006). Providing data across individuals' lives makes the DDB's parish registers excellent for conducting life course research.

The catechetical examination records (husförhörslängder) explain why Sweden's parish registers are exceptionally rich. Since the seventeenth century, the ministers had to keep these records on an annual basis to document parishioners' knowledge of the catechism and their reading skills (Nilsdotter Jeub, 1993). In these records, the ministers also made notes about their individual impairments (lytesmarkeringar), which indicate disabilities (Drugge, 1988; Haage, 2017; Rogers & Nelson, 2003). Parishioners whom the ministers labelled as disabled have been manually categorised as such for the purposes of this study, since the DDB has not consistently coded this type of information. Due to translation issues, both across time and between languages, we group similar types of disabilities as shown in Table 1 and only account for relatively evident impairments, such as auditory and visual defects and another few types of physical or mental dysfunctions. This facilitates comparisons both within the group of people with disabilities and with non-disabled parishioners in the Sundsvall region selected from the parish registers. Consequently, individuals who were not reported to be blind, deaf mute, crippled or mentally disabled and so forth (Tables 1 and 2) we recognise as having no disabilities. The latter people represent typical life trajectories of the population living in the Sundsvall region.

| Blind | Visual defects, including weak-sighted, short-sighted and blind |

|---|---|

| Deaf mute | Hearing or communication dysfunctions, ranging from bad hearing to deafness, and from difficulties speaking to stammering to mute |

| Crippled | Physical dysfunctions, e.g. lame, limping, walking with crutches, missing body parts, harelipped, small in size |

| Mental disabilities | Mental dysfunctions, e.g. foolish, silly, less cognisant (mindre vetande), insane, feeble-minded or crazy |

| Multiple disabilities | Combination of two or more of the above disabilities |

Source: Digitized parish registers, the Sundsvall region, Demographic Data Base, Umeå University, Sweden

Notes: On the categorisation of mental disabilities, see BiSOS. (1907) A. Befolknings-statistik. Statistiska Central-Byråns underdåniga berättelse för år 1900. Tredje afdelningen. Stockholm: SCB.

3.2 DATASET AND METHODS

In order to focus upon young people who were in the beginning of the transition to adulthood, the dataset comprises 8,874 unique 15-year-old persons born between 1820 and 1860, of whom 117 had different forms of impairment (Table 2). At the start of observation (age 15 years), none of them were married and none had any children, and only a few had any occupation reported. From then onwards, we observe them for a maximum of 18 years (to age 33 years) to investigate how disabilities influenced their life courses, focusing on the three events of first employment, first marriage and first occasion of parenthood.

| Disability category | Men N | Women N | Total N |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blind | 9 | 5 | 14 |

| Deaf mute | 23 | 13 | 36 |

| Crippled | 19 | 5 | 24 |

| Mental disabilities | 20 | 15 | 35 |

| Multiple disabilities | 4 | 4 | 8 |

| Sum with disabilities | 75 | 42 | 117 |

| Sum without disabilities | 4385 | 4372 | 8757 |

| Total | 4460 | 4414 | 8874 |

Source: Digitized parish registers, the Sundsvall region, Demographic Data Base, Umeå University

Notes: All individuals were born between 1820 and 1860 and were 15 years old at start of observation.

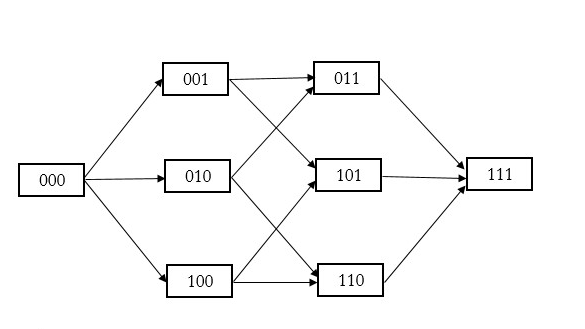

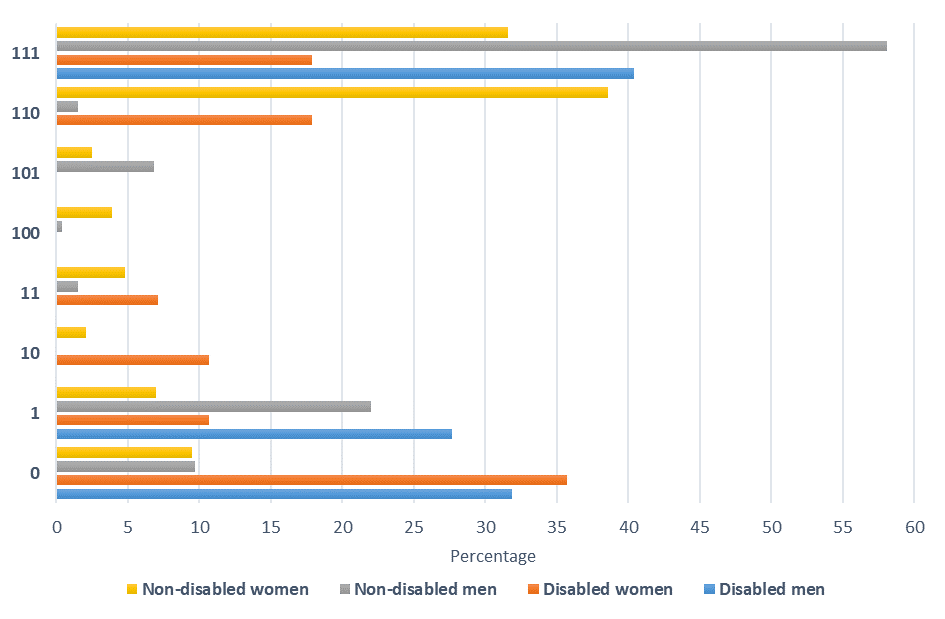

Having access to longitudinal individual-level data on people enables the method of sequence analysis (Abbott, 1990, 1995; Aisenbrey and Fasang, 2010; Oris & Ritschard, 2014), which we explain and employ more extensively in another study (Vikström, Häggström Lundevaller & Haage, 2017). Broadly conceived, it helps to examine a series of events during an extended period of the life course to identify how disability, for example, interfered with life. A sequence is the chronological states that one person holds over his or her lifetime, here from 15 to 33 years. This age interval constitutes our "observation window" of the trajectory and the events of occupation, marriage and parenthood we look for. As will be evident in the results section, the most common state at the start of observation (age 15) was 0. This refers to "zero" events and means that the individuals had no occupation and were not married and had no children. This state changes if one event in the series of events being analysed occurs. Figure 2 demonstrates the different states and transitions we observe in our sequence analysis. To illustrate the method further, Table 3 outlines the life sequence of the woman and man referred to in the Introduction. While it shows three different states of Anna Brita – who got her first job as maidservant when she was 17 years old, married at the age of 26 and gave birth to her first child in the following year – the life sequence of Nils Jonas only has the event of occupation. At the age of 18, he began working as a farmhand, a job he held throughout the whole observation time, but did not marry or become a father.

Figure 2. Image of the different states and transitions under study in the sequence analysis of the individuals' life trajectories (from 15 to 33 years of age).

Explanations of states:

000 = No occupation/No marriage/No child; 001 = Occupation/No marriage/No child;

010 = No occupation/No marriage/Child; 011 = Occupation/No marriage/Child;

100 = No occupation/Marriage/No child; 101 = Occupation/Marriage/No child;

110 = No occupation/Marriage/Child; 111 = Occupation/Marriage/Child

| The life sequence of Anna Brita (deaf-mute) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Age | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | 32 | 33 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 101 | 111 | 111 | 111 | 111 | 111 | 111 | 111 | |

| The life sequence of Nils Jonas (weak-sighted) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Age | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | 32 | 33 | |

| State | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

Explanations of states:

0 = No occupation/No marriage/No child; 1 = Occupation/No marriage/No child;

10 = No occupation/No marriage/Child; 11 = Occupation/No marriage/Child;

100 = No occupation/Marriage/No child; 101 = Occupation/Marriage/No child;

110 = No occupation/Marriage/Child; 111 = Occupation/Marriage/Child

As for the first job, this appears from the first occupational notes recorded in the parish register, which we regard as indicative of people's employment and transition to the labour market. However, if there is flawed documentation of occupation in the parish registers, or indeed if it is absent, this does not necessary imply that individuals did not work, nor does the recognition of them as being unskilled labourers, farmworkers or maidservants, for instance, confirm that they were actually employed in these occupations. Historians have noted that ministers' registration of people's occupations in this type of population record is not always consistent, and particularly so regarding women and especially if they were married (Leeuwen, Maas & Miles, 2002; Putte & Miles, 2005); Vikström, 2010). Similar to the practice adopted in those studies, we conclude that if there are occupational notes about individuals, which is frequently the case in the Swedish parish registers and particularly for men, it is most likely that they performed the type of work reported and it indicates their occupational status with some degree of accuracy. The two events of people's first marriage and first child are less difficult to determine, as the ministers documented these types of events and their exact dates more systematically than occupational changes. The same is true for the other two events we make some account of, death or migration from the parish before the age of 33, since they were also recorded carefully in the registers. All our analyses are performed in the statistical environment R, complemented with the package and toolbox TraMineR (Life Trajectory Miner for R) (Gabadinho, Ritschard, Müller & Studer, 2011; Gabadinho, Studer, Müller, Buergin & Ritschard, 2015).

4 RESULTS: THE OCCURRENCE AND TIMING OF THE EVENTS

First, we focus on the individuals with disabilities to get a view of their life sequences by type of disability and gender, and make comparisons between them and the control group comprising individuals not having disabilities. We also classify the first job according to types of occupations for the men and women in the two groups. Then, we examine whole life sequences in both groups for the individuals that we can follow from 15 to 33 years of age, excluding all those who died or migrated during observation.

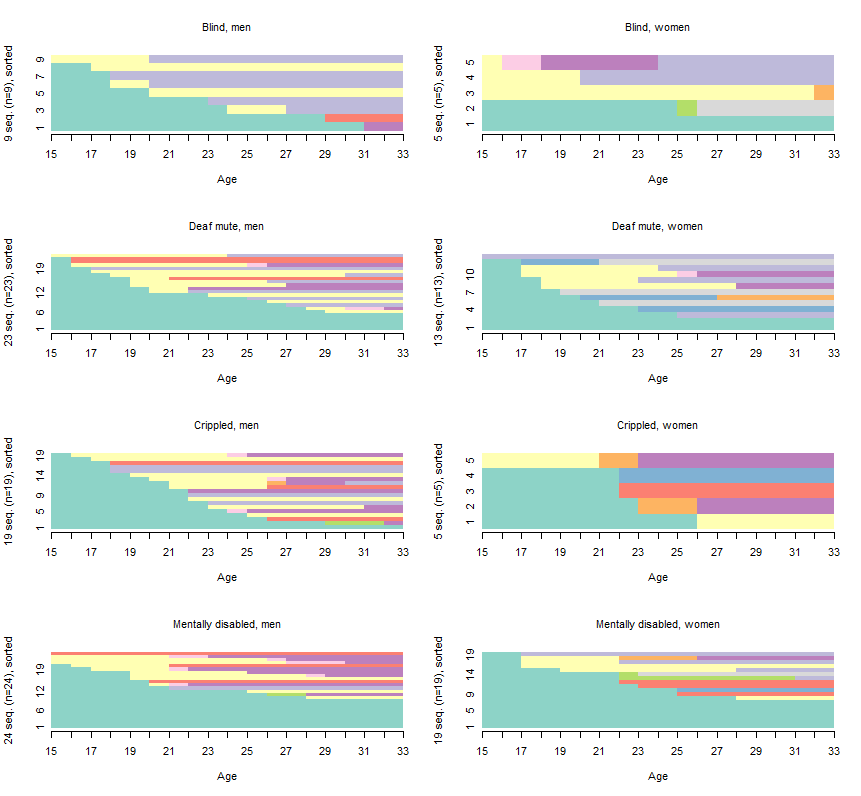

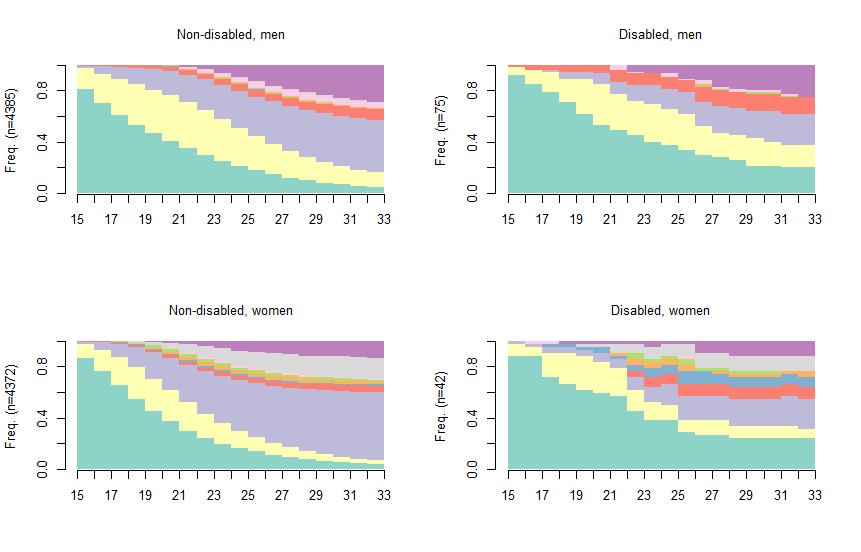

Figure 3 considers all the men and women with disabilities (N=117). The horizontally stacked boxes show their individual states across the trajectory depending on the events they experienced, or the absence thereof. The different states are coloured and placed in their successive positions. Every person thus gives rise to a row visualising the sequences by gender and type of disability, for example, how he/she transitioned from having no occupation to having one, from being unmarried to married and so forth. Anna Brita represents the seventh row from below among the 13 women recognised as deaf-mute, while the eighth row among the nine men labelled blind shows the life sequence of Nils Jonas.

Source: Digitized parish registers, the Sundsvall region, Demographic Data Base, Umeå University

Figure 3. Individual state sequences of people with disabilities per type of disability and gender during observation of their life trajectory (from 15 to 33 years of age).

Explanations:

The trajectory representing no job, no marriage and no childbearing (green-coloured state) during observation is visible among all regardless of the individuals' types of disability and gender, but it is most apparent among those with mental disabilities. Yet, in all disability groups, there were people who found a first job and eventually moved on to marriage and parenthood. As for those who got an occupation, married and gave birth to a child (purple-coloured state), representing the expected pathway in the nineteenth century, persons with all kinds of disabilities experienced this, but with some variation; for instance, only one out of 19 women with mental disabilities did. Illegitimate offspring (blue- and orange-coloured states) were evident among all disabled women, but to the least extent among those having visual impairments. Figure 3 acknowledges that a few of them died during observation (red-coloured state) while some more migrated (dark-grey-coloured state). Migrants appear across all disability types except for female "cripples," and only a few among men and women having mentally disabilities. Even though both the occurrence and timing of the events are visible by the colourful charts, the individual rows of Figure 3 are difficult to grasp except that they underline the diverse directions life could take for men and women with disabilities. To what extent their directions differed from people without disabilities will be evident below.

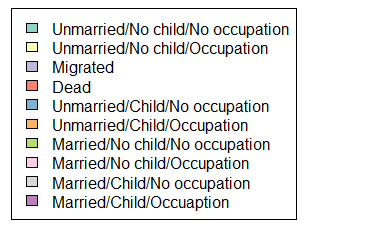

Figure 4 includes all individuals (N=8,874) to clarify how disabilities shaped humans' trajectories concerning both the occurrence and timing of all the events. The proportion of men who did not get any occupation, remained unmarried and did not have any children (green-coloured state) is considerably larger among men with disabilities than men without. At the age of 28, the slope for the former men levels off at about 20%, while for the latter men it continues to decrease. This suggests that disabled men who left the "'green" state due to gaining an occupation took up work later in life. Death (red-coloured state) is the only state where men with disabilities were proportionally much greater than among non-disabled peers, while the latter out-migrated to a significantly higher extent (dark-grey-coloured state). The state equal to occupation, marriage and family formation (purple-coloured state) shows a slightly larger share among men without a disability, while the proportion among those who had a job but did not experience marriage or parenthood (yellow-coloured state) is somewhat lower compared to disabled men.

Source: Digitized parish registers, the Sundsvall region, Demographic Data Base, Umeå University

Figure 4. Relative distribution of states by age per gender and disability during observation (from 15 to 33 years of age).

Explanations:

Even though the graphs for women with disabilities are influenced by issues with the source material to some degree, largely as a result of the small number of disabled women relative to the female control group and as a consequence of pre-marital births being recorded for women to a greater degree than for men, Figure 4 indicates that some of them moved through the sequence of occupation, marriage and child (purple-coloured state), or through marriage and then parenthood without any occupation (light-grey-coloured state). Similar to the men, the women with disabilities did so to a lesser extent and at a slower pace than their counterparts without disabilities. The state equal to bearing a child outside marriage and/or occupation (blue- or orange-coloured states) and the state representing death (red-coloured state) show higher proportions of disabled women than of non-disabled women, while the latter show a profoundly higher share of out-migration (dark-grey-coloured state). The events of dying and moving out break our observation of the life sequences. About 24% of the individuals with disabilities, both men and women, departed from their parish before they turned 33 years old. This was a small share compared to the great proportion of migrants found among those not having disabilities, among whom more women than men left the parish (53% and 41% respectively). The significant migration of the latter helps explain their lower share of mortality than among those having disabilities (11.5% and 7.5% respectively), as migrants may have passed away in parishes beyond our observation.4

The graphs of Figure 4 indicate that having a job was less frequently the case among people with disabilities. While 52% of the women without disabilities found work during observation, only 42% of the disabled women did. This difference was less obvious among the men (71% and 68% respectively).5 However, it is also important to inquire into the first jobs of those recorded as in employment. Our examination of the men and women in the two groups suggests that disability did not markedly shape the type of work followed by individuals. Among the women, about nine in ten worked as maidservant (piga), no matter whether they were impaired or not, just as did Anna Brita. Due to their gender, women were not employed in the sawmill industries that increasingly hired male unskilled labourers from the 1860s onward, though not Nils Jonas. As farmhand (dräng), he held the most typical occupation for young men in the sample. About 45% of the disabled men were farmhands while unskilled labourers made up the second most frequent job, accounting for 20% of them. The latter percentage was higher among non-disabled men having jobs (25%) while proportionally fewer of them were farmhands (41%). Beside craftsmen such as shoemakers and tailors, for example, farmers and crofters and sailors exemplify a few other common occupations among the men regardless of whether they had disabilities or not. In all, there is no evidence that individuals with disabilities who held occupations gathered into a few specific jobs that made them differ from their non-disabled peers. The only big difference was that having disabilities was less associated with holding any occupation at all and especially among the women.

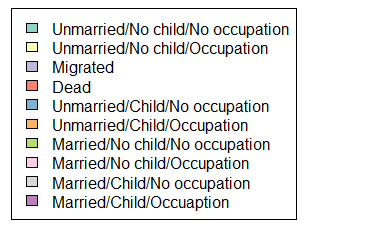

We now turn to the occurrence of events among people possible to follow from 15 right through to 33 years of age, who did not die or migrate during that period. As they did not migrate or die while we observe them, they had the same amount of time to experience the events in question, which provides further clues to whether people with disabilities differed from those who did not with regard to getting a job, marrying or having a child.6

Source: Digitized parish registers, the Sundsvall region, Demographic Data Base, Umeå University

Figure 5. Relative distribution of states at the end of observation by gender and disability after 18 years of observation (from 15 to 33 years of age).

Explanations of states:

0 = No occupation/No marriage/No child; 1 = Occupation/No marriage/No child;

10 = No occupation/No marriage/Child; 11 = Occupation/No marriage/Child;

100 = No occupation/Marriage/No child; 101 = Occupation/Marriage/No child;

110 = No occupation/Marriage/Child; 111 = Occupation/Marriage/Child

According to Figure 5, roughly 30% of the men with disabilities and almost 40% of their female peers did not experience any of the events under consideration here (state 0). This means they did not hold any occupation during the whole observation time, neither did they marry or have a child. Only about 10% of the people without disabilities ended up in that state (0). For them, getting a job, marrying and bearing a child (state 111) was thus a more common trajectory and especially among the men (58%) compared to disabled men (40%). In contrast to men being breadwinners before marriage, women married without having first held any occupation (state 110), but this particular state was twice as large among the women with no disabilities (40%) as among their disabled counterparts (20%).7 These comparative results make the life trajectory of Anna Brita, who moved through all the events, less representative of her female peers with disabilities. Regardless of disability, considerably more men than women took up an occupation and stayed single and childless (state 1) throughout our observation, just as did Nils Jonas. Despite having an occupation, he was one of quite many disabled men (28%) who remained unmarried (state 1) while this was less the case for non-disabled men (22%), primarily because they had transitioned into the state of marriage and family formation (states 110 and 111). One look at the states implying marriage (states 100, 101, 110, 111) makes clear that women with disabilities were the individuals marrying to the lowest extent (36%), followed by disabled men (40%), non-disabled men (67%) and women (76%). Finally, while only about 7% of the latter women gave birth to illegitimate offspring (states 10 and 11), almost 20% of women with disabilities did. Although this result requires further investigation, it may indicate that disabilities made women subject to sexual abuse and a higher level of vulnerability.

5 CONCLUDING REMARKS

In the nineteenth century, essential events associated with the transition to adulthood, such as getting a job, marrying and parenthood, marked people's expectations and experiences of life. Our aim was to clarify the extent to which and in what ways disabilities influenced the occurrence and timing of these events across the life course of a young population comprising 8,874 individuals in the Sundsvall region, Sweden during the nineteenth century. During an extended period (between ages 15 and 33 years), when young adults were to seek their livelihood and establish themselves, we observed both people with disabilities and those who did not in parish registers digitized by the Demographic Data Base (DDB). In suggesting individuals' involvement in the labour market and marriage market, we view the events of work, marriage and parenthood as indicative for their social inclusion in society.

One major conclusion is that our results provide a comparatively comprehensive picture of how people with disabilities moved through their young adult life. We find a great many differences between how their trajectories developed regarding work and family formation compared to those without disabilities. First, fewer of both the disabled men and women found a job, but if they did, they took up similar occupations allocated to the lower social strata as did their non-disabled peers. Second, individuals were less inclined to marry a spouse and form a family if disability was present in life. In all, our analysis clearly demonstrates that disability impeded people's opportunities to involve themselves in work and family life and thus in society. This result echoes previous disability history results based on other sources and methods showing that disabilities afflicted those concerned. We not only find that disabilities limited individuals' establishment in the labour market but even more impeded their opportunities in the partner market. Even though our findings relate to a distant period in history and concern a small region of nineteenth-century Sweden, they resemble the difficulties with life and labour that disabled people still experience today.

Yet another conclusion is that our findings reveal a diverse picture of the multiple and varied impacts disability had on human experience in the past. The different life trajectories of Anna Brita and Nils Jonas are evidence of this. She was a deaf-mute woman who worked as a maidservant and then entered into marriage and experienced a family life while he, a weak-sighted farmhand, did not. Having hearing and visual impairments, as they had, or being physically disabled, did not impede the expected pathway towards work and family as much as did mental disabilities. While the life trajectory of Anna Brita was more exceptional, the one of Nils Jonas was more representative of the group of people with disabilities. As he exemplifies, our results do not recognise work as key to the enjoyment of a family life for people with disabilities. Even though they and their maintenance probably benefitted more from having a job than not, it is notable that it did not necessarily lead to marriage and a family as often for them as for individuals without disabilities. Men held the same types of occupations to about the same extent, but those with disabilities did not transition to marriage to the level of men in occupations but with no disabilities; thus, fewer of the former men came to share a life with a wife and children. It seems as if their ability to work did not necessarily result in a sufficient income to afford a family and made them less attractive in the partner pool. Nineteenth-century men were expected to become "breadwinners" and provide for themselves, their wives and their families, by taking up work as farmhands, craftsmen, or in factories. Some such manual jobs could be difficult to complete for men with disabilities and employers may have hesitated to hire them on regular basis if they did not regard these men as fully fit for work. Most likely, these circumstances worked to lessen disabled men's opportunities to establish themselves in the labour market and gather the material resources for marrying and building a family. Although women were not expected to act as major providers and their jobs were primarily in the domestic sector, disability impeded their work and involvement in the marriage market and even more than for men it would seem. That disabilities implied higher levels of illegitimacy for women, probably played a part in their low marital prospects.

Finally, we would like to stress that our life course analysis reveals that people living with disabilities also experienced possibilities in the labour and marriage markets. Our demographic results do not propose that disability implied social exclusion from work and family for all concerned, as Anna Brita was not unique in having a disability and a job followed by marriage and childbearing. Her example, and our study more generally, reveal a great deal of agency among people living with disabilities some 150–200 years ago, primarily in the labour market but also in the marriage market. This suggests that they met tolerant attitudes from peers in their surrounding community, some of whom lived and worked together with them, hired or married them. It was in the parish or community, and not in institutions, that the large proportion of the young disabled persons we study lived, close to their relatives and known to local people who seem to have been less concerned at any possible limitations caused by their impairments. Knowing more about who Anna Brita married, for instance, and how her life or that of Nils Jonas developed until death would provide further clues as to what living with disabilities entailed historically.

Acknowledgments

This study is part of a project headed by Lotta Vikström that has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Grant Agreement No. 647125), 'DISLIFE Liveable Disabilities: Life Courses and Opportunity Structures Across Time'. The present study is also part of another project led by Lotta Vikström, 'Experiences of disabilities in life and online: Life course perspectives on disabled people from past society to present', funded by the Wallenberg Foundation (Stiftelsen Marcus och Amalia Wallenbergs Minnesfond). The authors are grateful to the useful feedback we received when a draft of the study was presented at the Fifth Annual Conference of Alter (European Society for Disability Research) in Stockholm, Sweden, June 30 – July 1, 2016. We also wish to thank the anonymous reviewers and guest-editors for providing suggestions on how to advance our study. Finally, we are grateful to all the support regarding both research and data that we enjoy from our colleagues at the Centre for Demographic and Ageing Research (CEDAR) and the Demographic Data Base (DDB), Umeå University, Sweden.

REFERENCES

- Abbott, A. "A Primer on Sequence Methods." Organization Science, 1.4 (1990): 375–392. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1.4.375

- Abbott, A. "Sequence Analysis: New Methods for Old Ideas." Annual Review of Sociology, 21 (1995): 93–113. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.so.21.080195.000521

- Aisenbrey, A., and Fasang, A. E. "New Life for Old Ideas: The 'Second Wave' of Sequence Analysis Bringing the 'Course' Back Into the Life Course." Sociological Methods & Research, 38.3 (2010): 420–462. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124109357532

- Alm Stenflo, G. Demographic Description of the Skellefteå and Sundsvall Regions during the 19th Century. Umeå: Demographic Data Base, 1994

- Arvidsson, J., Widén, S., and Tideman, M. "Post-school options for young adults with intellectual disabilities in Sweden." Research and Practice in Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 2.2 (2015): 180–193. https://doi.org/10.1080/23297018.2015.1028090

- Att följa levnadsförhållanden för personer med funktionshinder - Slutrapport. Stockholm: National Board of Health and Welfare, 2009.

- Barnes, C., and Mercer, G. "Disability, work, and welfare challenging the social exclusion of disabled people." Work, Employment & Society, 19.3 (2005): 527–545. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017005055669

- Barnes, C., and Mercer, G. Exploring Disability. A Sociological Introduction (Second ed.). Cambridge Polity Press, 2010.

- Bengtsson, S. "Arbete för individen och samhället." In Utanförskapets historia - om funktionsnedsättning och funktionshinder, edited by Engwall, K. and Larsson S., 45–;57. Lund: Studentlitteratur, 2012.

- Bergman, M. "Constructing communities: The establishment and demographic development of sawmill communities in the Sundsvall district, 1850–1890." PhD diss., Umeå University, 2010.

- BiSOS. A. Befolknings-statistik. Statistiska Central-Byråns underdåniga berättelse för år 1900. Tredje afdelningen. Stockholm: SCB, 1907.

- Blackie, D. "Disabled Revolutionary War Veterans and the Construction of Disability in the Early United States, c. 1776-1840." PhD Diss., University of Helsinki, 2010.

- Borsay, A. Disability and Social Policy in Britain since 1750. Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005.

- Bras, H., Liefbroer, A. C., and Elzinga, C. H. "Standardization of pathways to adulthood? An analysis of Dutch cohorts born between 1850 and 1900." Demography, 47.4 (2010): 1013–1034. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03213737

- Brändström, A. "Illegitimacy and Lone-Parenthood in XIXth Century Sweden. Annales de Démographie Historique, 2 (1998): 93–;114.

- Demographic Data Base (DDB). Digitized Parish Registers, the Sundsvall region, 1800–1892.

- De Veirman, S. "Breaking the silence: The experiences of deaf people in East Flanders, 1750–1950: A life course approach." PhD Diss., Gent University, 2015.

- De Veirman, S., Haage, H., and Vikström, L. "Deaf and unwanted? Marriage characteristics of deaf people in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Belgium: a comparative and cross-regional perspective. Continuity and Change, 31.2 (2016): 241–273. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0268416016000230

- Dribe, M. "Leaving Home in a Peasant Society. Economic Fluctuations, Household Dynamics and Youth Migration in Southern Sweden, 1829–1866." PhD Diss., Lund University, 2000.

- Drugge, U. Om husförhörslängder som medicinsk urkund. Psykisk sjukdom och förståndshandikapp i en historisk källa. Umeå: Scriptum nr 8. Rapportserie utgiven av forskningsarkivet vid Umeå universitet, 1988.

- Edvinsson, S. "Den osunda staden: Sociala skillnader i dödlighet i 1800-talets Sundsvall." PhD Diss., Umeå University, Demographic Data Base, 1992.

- Elder Jr., G. H., Kirkpatrick Johnson, M., and Crosnoe, R. "The Emergence and Development of Life Course Theory." In Handbook of the Life Course, edited by Mortimer, J. T., and J. Shanahan, M. J., 3–19. New York: Springer Science+Business Media, 2004.

- Engberg, E. "I fattiga omständigheter: Fattigvårdens former och understödstagare i Skellefteå socken under 1800-talet." PhD Diss., Umeå University, 2005.

- Foucault, M. Madness and civilization: A history of insanity in the age of reason. New York: Pantheon books, 1965.

- Förhammar, S. Från tärande till närande: Handikapputbildningens bakgrund och socialpolitiska funktion i 1800-talets Sverige. Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell, 1991.

- Förhammar, S., and Nelson, M. C. eds. Funktionshinder i ett historiskt perspektiv. Lund: Studentlitteratur, 2004.

- Franklin, P. A. "Impact of disability on the family structure." Social Security Bulletin, 40.5 (1977): 3–18.

- Gabadinho, A., Ritschard, G., Müller, N. S., and Studer, M. "Analyzing and Visualizing State Sequences in R with TraMineR." Journal of Statistical Software, 40.4 (2011): 1–37. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v040.i04

- Gabadinho, A., Studer, M., Müller, N., Buergin, R., and Ritschard, G. "Package "TraMineR" Trajectory Miner: A Toolbox for Exploring and Rendering Sequences." Retrieved (October 6, 2015) from http://traminer.unige.ch

- Gaunt, D. Familjeliv i Norden. Stockholm: Gidlunds förlag, 1983.

- Giele, J. Z., and Elder Jr., G. H. "Life Course Research. Development of a Field." In Methods of Life Course Research. Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches, Methods of Life Course Research. Qualitative and Quantitative, edited by Giele, J. Z., and Elder Jr. G. H., 5–27. Thousand Oaks California: SAGE Publications Inc, 1998.

- Haage, H. "Disability in Individual Life and Past Society: Life-Course Perspectives on People with Disabilities in the Sundsvall Region of Sweden in the Nineteenth Century." PhD Diss., Umeå University, 2017.

- Haage, H., Häggström Lundevaller, E., and Vikström, L." Gendered death risks among disabled individuals in Sweden: A case study of the 19th-century Sundsvall region." Scandinavian Journal of History, 41.2 (2016): 160–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/03468755.2016.1155859

- Haage, H., Vikström, L., and Häggström Lundevaller, E. "Disabled and unmarried? Marital chances among disabled people in nineteenth-century northern Sweden" Essays in Economic and Business History, 35.1 (2017): 207–238.

- Hajnal, J. "European Marriage Patterns in Perspective." In Population in History: Essays in Historical Demography, edited by Glass D. V., and Eversley, D. E. C., 101–143. London: Edward Arnold Publishers Ltd, 1965.

- Harnesk, B. Legofolk. PhD Diss., Umeå University, 1990.

- Horrell, S., and Humphries, J. "The origins and expansion of the male breadwinner family: The case of nineteenth-century Britain." International Review of Social History, 42.S5 (1997): 25–64. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020859000114786

- Hutchison, I. A History of Disability in Nineteenth Century Scotland. New York: The Edwin Mellen Press, 2007.

- Jacobsson, M. "Att blifva sin egen: Ungdomars väg in i vuxenlivet i 1700- och 1800-talens övre Norrland." PhD Diss., Umeå University, 2000.

- Jaeger, P. T., and Bowman, C. A. Understanding disability: Inclusion, access, diversity, and civil rights. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger Publisher, 2005.

- Janssens, A. The Rise and Decline of the Male Breadwinner Family? Studies in Gendered Patterns of Labour Division and Household Organisation (Vol. 5). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

- Jeppsson Grassman, E., and Whitaker, A. Ageing with disability. Bristol: The Policy Press, 2013.

- Kavanagh A.M., Krnjacki L., Beer A., et al. "Time trends in socio-economic inequalities for women and men with disabilities in Australia: evidence of persisting inequalities. International Journal of Equity Health, 12.73 (2013) https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-9276-12-73

- Kok, J. "Principles and prospects of the life course paradigm." Annales de Démographie Historique, 1 (2007): 203–230. https://doi.org/10.3917/adh.113.0203

- Kudlick, C. "Modernity's Miss-Fits: Blind Girls and Marriage in France and America, 1820-1920." In Women on Their Own: Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Being Single, edited by Bell R. M., and Yans-McLaughlin, V, 201–218 Rutgers University Press, 2008.

- Kudlick, C. J. "Disability history: Why we need another 'other'." The American Historical Review, 108.3 (2003): 763–793.

- Leeuwen, M. V., Maas, I., and Miles, A. HISCO: Historical international standard classification of occupations. Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2002.

- Longmore, P. K., and Umansky, L. eds. The New Disability History: American Perspectives. New York: New York University Press, 2001.

- Lundh, C. The World of Hajnal Revisited. Marriage Patterns in Sweden 1650-1990. Lund: Lund Papers in Economic History (No. 60), 1997.

- Lundh, C. "Servant migration in Sweden in the early nineteenth century." Journal of Family History, 24.1 (1999): 53-73. https://doi.org/10.1177/036319909902400104

- Lundh, C. Life Cycle Servants in Nineteenth Century Sweden – Norms and Practice. Lund: Lund Papers in Economic History (No. 84), 2003.

- Nielsen, K. "Helen Keller and the Politics of Civic Fitness." In The New Disability History. American Perspectives, edited by Longmore, P. K., and Umansky, L., 268-290. New York: New York University Press, 2001

- Nilsdotter Jeub, U. Parish Records: 19th Century Ecclesiastical Registers. Umeå: Umeå University: Demographic Data Base, 1993.

- Oliver, M. Understanding Disability. From Theory to Practice. New York: St. Martins Press cop., 1996.

- Oliver, M. The Politics of Disablement. Critical Texts in Social Work and the Welfare State, London, Macmillan Education, 1990.

- Olsson, C. G. "Omsorg & Kontroll. En handikapphistorisk studie 1750–1930." PhD Diss., Umeå University, 2010.

- Olsson, I. "Att leva som lytt. Handikappades livsvillkor i 1800-talets Linköping." PhD Diss., Linköping University, 1999.

- Oris, M., and Ritschard, G. "Sequence Analysis and Transition to Adulthood: An Exploration of the Access to Reproduction in Nineteenth-Century East Belgium." In Advances in Sequence Analysis: Theory, Methods, Applications, edited by Blanchard, P., Bühlmann, F., and Gauthiers, J-A., 2 (2014): 151–167. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-04969-4_8

- Petersson, B. "Den farliga underklassen: Studier i fattigdom och brottslighet i 1800-talets Sverige." PhD Diss., Umeå university, 1983.

- Priestley, M. Disability. A Life Course Approach. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2003.

- Putte, B. V. D., and Miles, A. "A social classification scheme for historical occupational data." Historical Methods: A Journal of Quantitative and Interdisciplinary History, 38.2 (2005): 61–94. https://doi.org/10.3200/HMTS.38.2.61-94

- Reine, E., Palmer, E., and Sonnander, K. "Are there gender differences in wellbeing related to work status among persons with severe impairments?" Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 8.44 (2016): 772–783. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494816669638

- Rogers, J., and Nelson, M. C. "'Lapps, finns, gypsies, jews and idiots' modernity and the use of statistical categories in Sweden. Annales de Démographie Historique, 1.105 (2003): 61–79. https://doi.org/10.3917/adh.105.79

- Sandvin, J. "Loosening Bonds and Changing Identities: Growing Up with Impairments in Post War Norway." Disability Studies Quarterly, 23.2 (2003): https://doi.org/10.18061/dsq.v23i2.410

- Sainsbury, S., and Lloyd-Evans, P. Deaf worlds: A study of integration, segregation, and disability. Hutchinson Educational, 1986.

- Schur, L., Kruse, D., and Blanck, P. People with disabilities: Sidelined or mainstreamed? Cambridge University Press, 2013.

- Siminski, P. "Patterns of Disability and Norms of Participation through the Life Course: Empirical Support for a Social Model of Disability." Disability and Society, 18.6 (2003): 707–718. https://doi.org/10.1080/0968759032000119479

- Turner, D. M. Disability in eighteenth-century England: Imagining physical impairment, New York: Routledge. 2012.

- Turner, D. M., and Stagg, K. eds. Social histories of disability and deformity: Bodies, images and experiences. London: Routledge, 2006.

- Tøssebro, J., and Kittelsaa, A., eds. Exploring the Living Conditions of Disabled People. Lund: Studentlitteratur, 2004.

- Vikström, L. "Gendered routes and courses: The socio-spatial mobility of migrants to nineteenth-century Sundsvall, Sweden." PhD Diss., Umeå University, Demographic Data Base. 2003.

- Vikström, L. "Vulnerability among paupers: Determinants of individuals receiving poor relief in nineteenth-century northern Sweden." The History of the Family, 11.4 (2006): 223–239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hisfam.2006.12.004

- Vikström, L. "Illuminating the impact of incarceration: Life-course perspectives of young offenders' pathways in comparison to non-offenders in nineteenth-century northern Sweden." Crime, History and Societies, 12.2 (2008): 81–117. https://doi.org/10.4000/chs.361

- Vikström, L. "Identifying dissonant and complementary data on women through the triangulation of historical sources." International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 13 (2010): 211–221. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2010.482257

- Vikström, L. "Before and after crime: Life-course analyses of young offenders arrested in 19th century northern Sweden." The Journal of Social History, 44.3 (2011): 861–888. https://doi.org/10.1353/jsh.2011.0001

- Vikström, L., Haage, H., and Häggström Lundevaller E. "Sequence analysis of how disability influenced life trajectories in a past population from the nineteenth-century Sundsvall region, Sweden. Historical Life Course Studies, 4 (2017): 97–119.

- Vikström, P., Brändström, A., and Edvinsson, S. (2006). Longitudinal Databases: Sources for Analyzing the Life Course: Characteristics, Difficulties and Possibilities. History and Computing, 14.1-2 (2006): 109–128. https://doi.org/10.3366/hac.2002.14.1-2.109

- Whittle, J. "Servants in rural England c. 1450–1650: Hired work as means of accumulating wealth and skills before marriage. In The Marital Economy in Scandinavia and Britain 1400-1900, edited by M. Ågren and A. L. Erickson, 89–107. Aldershot Hants: Ashgate cop., 2005

Endnotes

- Department of Historical, Philosophical and Religious Studies, Centre for Demographic and Ageing Research (CEDAR), Umeå University, Sweden [SE-901 87 UMEÅ, SWEDEN, Phone: +46-90-7865015]

Return to Text - Umeå School of Business and Economics, Centre for Demographic and Ageing Research (CEDAR), Umeå University, Sweden [SE-901 87 UMEÅ, SWEDEN, Phone: +46-90-7865145]

Return to Text - Department of Historical, Philosophical and Religious Studies, Centre for Demographic and Ageing Research (CEDAR), Umeå University, Sweden [SE-901 87 UMEÅ, SWEDEN, Phone: +46-90-7865015]

Return to Text - During observation, disabled men died

to a slightly larger degree than did disabled women (13.3% and 9.5%,

respectively), while these mortality figures were lower among non-disabled

men and women (8.2% vs. 5.1%). In a previous study, we have shown

that disabilities were associated with higher premature mortality risks

(Haage, Häggström Lundevaller & Vikström, 2016).

Return to Text - Unfortunately, it is possible to

study only a few individuals with disabilities who also held occupations (51

men out of a total of 75, and 18 women out of a total of 42). This is less

of a problem concerning the reference group as it includes a higher number

of people (3,125 men out of a total of 4,385, and 2,269 women out of a total

of 4,372), cf. Table 2.

Return to Text - Pearson's chi-squared tests show

statistically significant P-value regarding the results of Figure 5

(3.63e-07 for men and P-value = 9.15e-12 for women), see Vikström,

Häggström Lundevaller & Haage (2017).

Return to Text - The profound absence of occupations

among the women does not imply that they did not work; it is primarily due

to poor documentation of their actual work in the sources. Similar to

historical population registers in general, Sweden's parish registers

under-report women's occupations (Vikström, 2010).

Return to Text