We used the phenomenon of prenatal genetic testing to learn more about how siblings of disabled people understand prenatal genetic testing and social meanings of disability. By interweaving data on siblings' conscious and unconscious disability attitudes and prenatal testing with siblings' explanations of their views of prenatal testing we explored siblings' unique relationships with disability, a particular set of perspectives on prenatal genetic testing, and examined how siblings' decision-making processes reveal their attitudes about disability more generally. In doing so we found siblings have both personal and broad stakes regarding their experiences with disability that impact their views.

Adult siblings of disabled people 1 constitute a unique, but often overlooked group (Arnold et al. 2012). Literature focused on adults siblings of disabled people has contributed to a growing interest in the roles siblings of disabled people may play in their disabled siblings' lives in areas such as employment (Hall & Kramer, 2009), future planning (Heller & Kramer, 2009), and balanced outcomes for siblings of disabled people (Hodapp et al., 2005). While siblings of disabled people are often strong advocates for and with their disabled brothers and sisters (Burke et al 2015), little is known about their attitudes about disability in general. Siblings' experiences with disabled family members may impact their attitudes about disability in unique and complex ways. It is important to know more about how siblings of disabled people understand social meanings of disability because siblings are more likely to work in disability-related fields (Eget, 2009), are more likely to take on increased caregiving roles for their disabled siblings (Burke et al., 2012), and may make decisions about whether to bear a disabled child based upon prenatal genetic testing results (Bryant et al., 2005).

Prenatal genetic testing is a set of medical technologies and practices that, through the use of several tests, diagnoses certain genetic conditions while the fetus is still in the womb. While prenatal genetic testing is closely related to prenatal genetic screening, this article will focus on testing, which provides diagnosis, rather than screening, which can only provide probabilities. Screening protocols were developed in order to help parents determine whether or not they should have invasive tests such as amniocentesis done. Screening tests include triple and quad screens, which test for the presence of certain proteins that may indicate certain genetic conditions, nuchal translucency testing, which measure physiological characteristics through ultrasound imaging, and new noninvasive screening, which extracts fetal DNA from the mother's bloodstream. Prenatal genetic testing is often done in a genetic counselor's office or at a physician's office. For some conditions, genetic testing is done by testing the parents' blood to determine their carrier status. This includes conditions such as cystic fibrosis and muscular dystrophy. Other testing techniques are more invasive, such as amniocentesis and chorionic villus sampling (CVS). These tests employ use of long needles to extract fetal DNA samples, and thus come with a very small risk of miscarriage, estimated at 0.1% for amniocentesis and 0.2% for CVS (Akolekar et al., 2015). The availability of termination on the basis of a genetic condition that leads to impairment or disability makes prenatal genetic testing a unique and high-stakes moment that reveals how social attitudes about disabled people impact medical and familial decision-making. While most medico-legal and bioethical authorities do not accord fetuses full personhood (Post, 1996; Gallagher, 1987), the fetus, particularly in North American contexts, has taken on various meanings and valences. As Monica Casper (1998) has put it, fetuses are "fertile signifiers" (p. 19). Thus, even though a disabled or potentially disabled fetus may differ ontologically from a disabled person, the role fetuses play in propelling forward imagined futures of people (Kafer, 2013; Rothschild, 2005) makes the issue of prenatal testing well-situated to explore both implicit and explicit attitudes about disability.

Siblings of disabled people, in particular, may represent a particular set of perspectives regarding prenatal genetic testing. Because of their kinship to a disabled person, they and their decision-making processes likely reveal something about their attitudes about disability in general. In making the connection between prenatal genetic testing and attitudes about disability, we draw upon disability rights critiques of prenatal genetic testing as expressing hostility or disvalue against disabled people (Gonter, 2004; Parens & Asch, 2000; Saxton, 1997). Disability rights activists and scholars note reported high levels of termination on the basis of a prenatal disability diagnosis, estimated between 68 and 72% of Down Syndrome fetuses in the U.S (Natoli et al., 2012). Disability rights activists and scholars have critiqued the availability and uses of prenatal genetic testing because of the high selective abortion rates, arguing that both the availability and use of prenatal testing reveal significant bias against disability (Parens & Asch, 2000).

The prevalence of prenatal genetic screening and testing, in addition to the core stakes of values of personhood and family, make prenatal genetic testing a useful lens to explore social attitudes and meanings of disability.

Attitude Measurement

Though attitudes do not fully explain social behavior, they are useful to study because they impact behavioral outcomes, and they help us understand social interactions, socialization, and prejudice formation (Antonak & Livneh, 2000). Explicit measures are those that examine conscious attitudes, as participants are cognizant of what is being measured (Antonak & Livneh, 2000). For example, many surveys would commonly fall under the umbrella of explicit measures. Implicit measures examine automatic processes, particularly as triggered to learned associations and external cues (Amodio & Mendoza, 2011). Amodio and Mendoza (2011) explain, "'implicit' refers to [lack of] awareness of how a bias influences a response, rather than to the experience of bias or to the response itself" (Amodio & Mendoza, 2011, p. 359). Thus, implicit attitudes explore the relationship between concepts and attitudes. Since implicit attitudes are related to social norms it is theorized that the majority of people hold negative implicit attitudes towards social minorities (Dovidio & Gaertner, 2004; Dovidio, Gaertner, Anastasio, & Sanitioso, 1992).

As people may feel pressure to conceal their explicit biases, or may not be aware they hold biases, much attitude and prejudice literature has shifted towards exploring both explicit and implicit attitudes (Amodio & Mendoza, 2011; Antonak & Livneh, 2000). For instance, disabled people are often portrayed as pitiable and warm, so it may be particularly taboo to overtly express prejudiced feelings towards them (Appelbaum, 2001; Garthwaite, 2011; Harris & Fiske, 2007; Imrie & Wells, 1993; Ostrove & Crawford, 2006; Stewart, Harris, & Sapey, 1999). Recent studies have begun examining implicit disability prejudice, particularly focusing on attitudes of different groups of people such as rehabilitation counseling students (Pruett & Chan, 2006), teachers (Federici & Meloni, 2008), physician assistant students (Archambault et al., 2008), child protective services employees (Proctor, 2011), nurses (Aaberg, 2012), etc. All of the aforementioned studies have found such groups highly favor nondisabled people and have high levels of implicit prejudice towards disabled people (Aaberg, 2012; Archambault et al., 2008; Federici & Meloni, 2008; Proctor, 2011; Pruett & Chan, 2006).

Although siblings of disabled people are uniquely positioned towards disability, no research has examined siblings' implicit disability attitudes. While their intimacy with disability and their closeness to their disabled sibling/s suggest they may have more positive explicit attitudes than other groups, less is known about how a sibling relationship with disability could impact siblings' implicit disability attitudes. We used the phenomenon of prenatal genetic testing as a probe for eliciting understandings about the technology itself and social meanings of disability. In doing so, we also explored variables that may impact siblings' views on prenatal testing as well as examined relationships between implicit and explicit disability attitudes and views on prenatal testing.

Method

Because siblings of disabled people have a unique relationship to disability their perspectives regarding prenatal genetic testing and diagnosis may reveal something about siblings' attitudes about disability in general. Thus, the aim of this study was to explore both the ways siblings understand prenatal testing technologies and how their views of prenatal testing may reveal attitudes towards disability. As a result, we analyzed implicit and explicit measures, and close-ended questions using quantitative methodology to track siblings' attitudes towards disability and prenatal testing. However, because we asked respondents to expand on their close-ended survey answers with open-ended questions, we also employed qualitative analysis to help us understand how people interpret experiences, construct concepts, and make things meaningful (Merriam, 2009). We deliberately incorporated mixed methodology in order to include unique measurement such as implicit association, as well as to examine this complex phenomenon through different and complicated experiences. As such, we have interwoven the quantitative and qualitative findings because participants were asked to explain their quantitative answers, and because the qualitative findings help us understand siblings' views and attitudes towards both disability and prenatal testing.

Measures

The Disability Attitudes Implicit Association Test. Implicit Association Tests (IATs), one of the most prominently used methods for measuring implicit views, have been used to study prejudice and associations regarding race, sexual orientation, and body size. The Disability Attitude Implicit Association Test (DA-IAT) (Greenwald et al., 1998) is the most widely used disability related IATs. The DA-IAT first presents participants with the two target-concept discriminations, 'disabled persons' and 'abled persons,' and the two attribute dimensions, 'good' and 'bad', displaying one target-concept discrimination and one attribute dimension on each side of the computer screen. For example, disabled persons and bad on the left side of the screen and abled persons and good on the right. Participants are then presented with stimuli and asked to sort them as quickly as possible. The DA-IAT measures response latencies as participants sort stimuli into stereotype consistent and inconsistent categories. Several studies have shown the DA-IAT's validity and reliability (Aaberg, 2012; Pruett, 2004; Pruett & Chan, 2006; Thomas, Vaughn, Doyle, & Bubb, 2013; White, Jackson, & Gordon, 2006). Moreover, Nosek et al. (2007) administered the DA-IAT to over 38,500 people and found it to have the strongest implicit effects over the other social group domains (Nosek et al., 2007).

The Symbolic Ableism Scale. The Symbolic Ableism Scale (SAS) (Friedman & Awsumb, in preparation), an explicit scale adapted from the Symbolic Racism Scale 2000 (Henry & Sears, 2002; Sears & Henry, 2003), measured participants' explicit bias. During the SAS participants' rate thirteen statements about disability on a seven point Likert scale from strongly disagree to strongly agree. For example, one statement participants are presented with is: 'any disabled person who is willing to work hard has a good chance of succeeding.'

| Prenatal Testing Questions |

|---|

| Have you or a partner been pregnant? |

| If so how many times? |

| How many children do you have? |

| Have you or your partner used prenatal genetic testing for disability in the past? |

| How likely are you to use prenatal genetic testing for disability in the future? (Sliding scale: extremely unlikely (1) to extremely likely (100)) |

| Please explain why you selected the answer you did (on the previous question). |

| What is your view on the use of prenatal genetic testing for disability? (Sliding scale: should never be used (1) to should always be used (100)) |

| Please explain why you selected the answer you did (on the previous question). |

| To what extent does your experience growing up as a sibling of a person with a disability influence your ideas about prenatal genetic testing? |

Others items. In addition to completing the DA-IAT and the SAS participants completed a number of questions about prenatal testing that were based on Bryant et al. (2005) and Wertz et al. (1991); see table 1 for the list of questions. We also asked participants about their demographics, including political orientation that was determined by moving a needle on a sliding scale from very liberal (1) to very conservative (100). Participants also answered questions about their relationships with disabled people at various levels (e.g., siblings, family, friends) and a sliding scale (similar to political orientation) about how close they feel to their disabled sibling/s. Finally, we asked participants if they were involved in a sibling advocacy group and if their disabled sibling/s participated in disability advocacy groups.

Participants

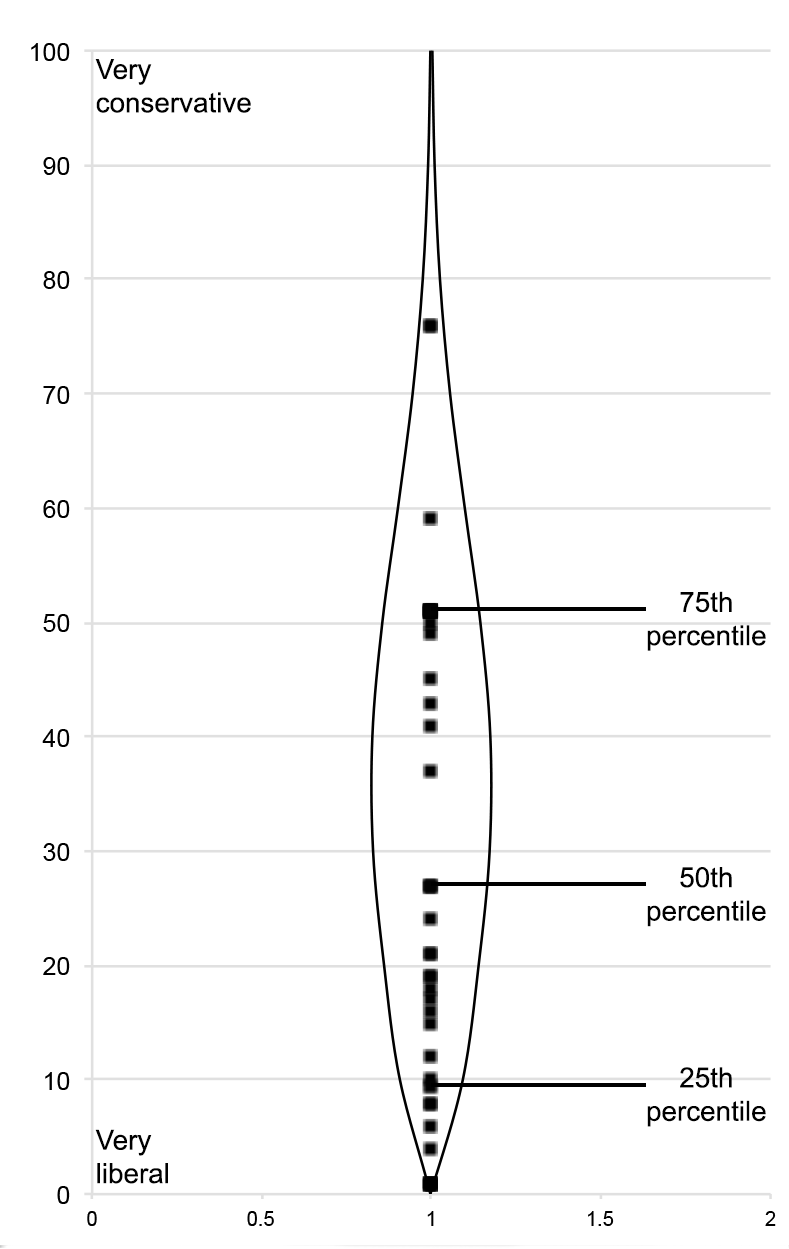

Forty-eight siblings participated in this study. Participant demographics are detailed in table 2. The mean age of participants was 38.23 years (SD = 13.28). Participants' mean political orientation, which was determined on a sliding scale from very liberal (1) to very conservative (100), was 30.63 (SD = 22.32), which falls in the liberal category; figure 1 details the distribution of political orientation scores.

| Demographics of Sample | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | n | % | |

| Gender | |||

| Woman | 43 | 89.6 | |

| Man | 5 | 10.4 | |

| Disability | |||

| No | 41 | 85.4 | |

| Yes | 7 | 14.6 | |

| Race | |||

| White | 38 | 79.2 | |

| Asian or Pacific islander | 3 | 6.3 | |

| Black | 3 | 6.3 | |

| Hispanic or Latino/a | 2 | 4.2 | |

| Middle Eastern | 1 | 2.1 | |

| Interracial | 1 | 2.1 | |

| Number of disabled siblings | |||

| One | 40 | 83.3 | |

| Two | 7 | 14.6 | |

| Four | 1 | 2.1 | |

Procedures

Participants were recruited through the Sibling Leadership Network, an organization that provides information and support to siblings of disabled people. Those siblings interested in participating accessed the study website and then completed an informed consent and exclusion criteria that verified they were a sibling of at least one person with a disability. The participants then were introduced to the DA-IAT, wherein they were instructed to push the 'E' and 'I' keys on the keyboard if stimuli belonged to categories on the left and right of the screen respectively. The DA-IAT stimuli are symbols of disabled and non-disabled people such as the wheelchair symbol and someone skiing. For the attribute dimensions good and bad the stimuli are words such as love and rotten. They were informed they should sort items as quickly as possible but with the least amount of errors. If they made a mistake and placed stimuli in the wrong category a red 'X' appeared in the middle of the screen until they corrected their answer. During the DA-IAT participants are then presented with seven blocks (rounds) of categorization tasks. The sequence of blocks is presented in table 3.

| Sequence of Blocks in the Disability Attitudes Implicit Association Test (DA-IAT) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blocks | No. of Trials | Function | Items Assigned to Left-Key Response | Items Assigned to Right-Key Response |

| 1 | 20 | Practice | Abled-persons | Disabled-persons |

| 2 | 20 | Practice | Good | Bad |

| 3 | 20 | Test Block 1a | Abled-persons AND good | Disabled-persons AND bad |

| 4 | 40 | Test Block 2a | Abled-persons AND good | Disabled-persons AND bad |

| 5 | 40 | Practice | Bad | Good |

| 6 | 20 | Test Block 1b | Disabled-persons AND good | Abled-persons AND bad |

| 7 | 40 | Test Block 2b | Disabled-persons AND good | Abled-persons AND bad |

| Note. The computer system randomizes if participants receive stereotype congruent or incongruent items first. | ||||

After completing the DA-IAT participants completed the Symbolic Ableism Scale, which included selecting responses on a seven-point Likert (strongly disagree to strongly agree) about 13 disability statements. Participants then completed the questions about prenatal testing, demographics, and other factors. After being thanked for their participation they were given the principle investigator's contact information if they should need any further debriefing.

Analysis

Implicit attitudes (DA-IAT scores) were calculated using Greenwald, Nosek, & Banaji's (2003) updated IAT scoring procedure. DA-IAT scores reveal the strength of preference for nondisabled or disabled people ranging from -2 to 2, with scores of -.14 to .14 revealing no preference for nondisabled or disabled people, .15 to .34 a slight preference, .35 to .64 a moderate preference, and .65 or greater a strong preference (Aaberg, 2012; Greenwald et al., 2003). Negative values of the same ranges reveal preferences for disabled people (Aaberg, 2012; Greenwald et al., 2003).

To determine participants' explicit attitudes (SAS scores), the applicable items were reverse keyed, and then all items were recoded from zero to one. Each participant's mean score then serves as his or her explicit score. Descriptive statistics were used for the rest of the quantitative data, and multiple regressions were run to determine significant relationships between prenatal testing questions, attitudes scores, and other factors.

Open-ended questions were analyzed using thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006). To do so, both researchers repeatedly read the data to become immersed. Then patterns across the data were unearthed and codes were generated using a theory-driven approach, which involves engaging with relevant literature (Kafer, 2013; O'Toole, 2013; Parens & Asch, 2000). Codes were then grouped into themes, reviewed, and revised when necessary. When both researchers mutually agreed upon the themes, we returned to the data and verified the themes accurately represented the data. Thematic analysis has been used to analyze open-ended survey responses, and is particularly useful in delineating similarities and differences both between respondents but also within a single respondent's answer (Manhire et al., 2007).

Findings

Participants' explicit scores on the SAS ranged from 0 to .60, with a mean of .28 (SD = .13). On the DA-IAT participants 2 had a mean score of .53 (SD = .44), which is considered a moderate preference for nondisabled people. Participants' implicit scores ranged from -0.63 (moderate preference for disabled people) to 1.29 (strong preference for nondisabled people), with 83.3% (n = 39) of participants preferring nondisabled people, 8.4% (n = 4) preferring disabled people, and 8.3% (n = 4) having no preference. The relationship between participants explicit and implicit scores are explored more in depth in Friedman (in press).

In addition to completing the explicit and implicit measures of disability prejudice participants completed a number of questions about prenatal testing. Table 4 details results from the general prenatal testing questions.

| Results from the General Prenatal Testing Questions | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Question | % | n | |

| Have you or a partner been pregnant? | |||

| No | 70.8 | 34 | |

| Yes | 29.2 | 19 | |

| If so how many times? | |||

| 0 | 70.8 | 34 | |

| 1 | 12.5 | 6 | |

| 2 | 6.3 | 3 | |

| 4 | 8.3 | 4 | |

| 5 | 2.1 | 1 | |

| How many children do you have? | |||

| 0 | 72.9 | 35 | |

| 1 | 4.2 | 2 | |

| 2 | 10.4 | 5 | |

| 3 | 12.5 | 6 | |

| Have you or your partner used prenatal genetic testing for disability in the past? | |||

| No | 84.3 | 39 | |

| Once | 10.9 | 5 | |

| More than Once | 4.3 | 2 | |

Personal stakes: Complicated views of disability and sibling experiences

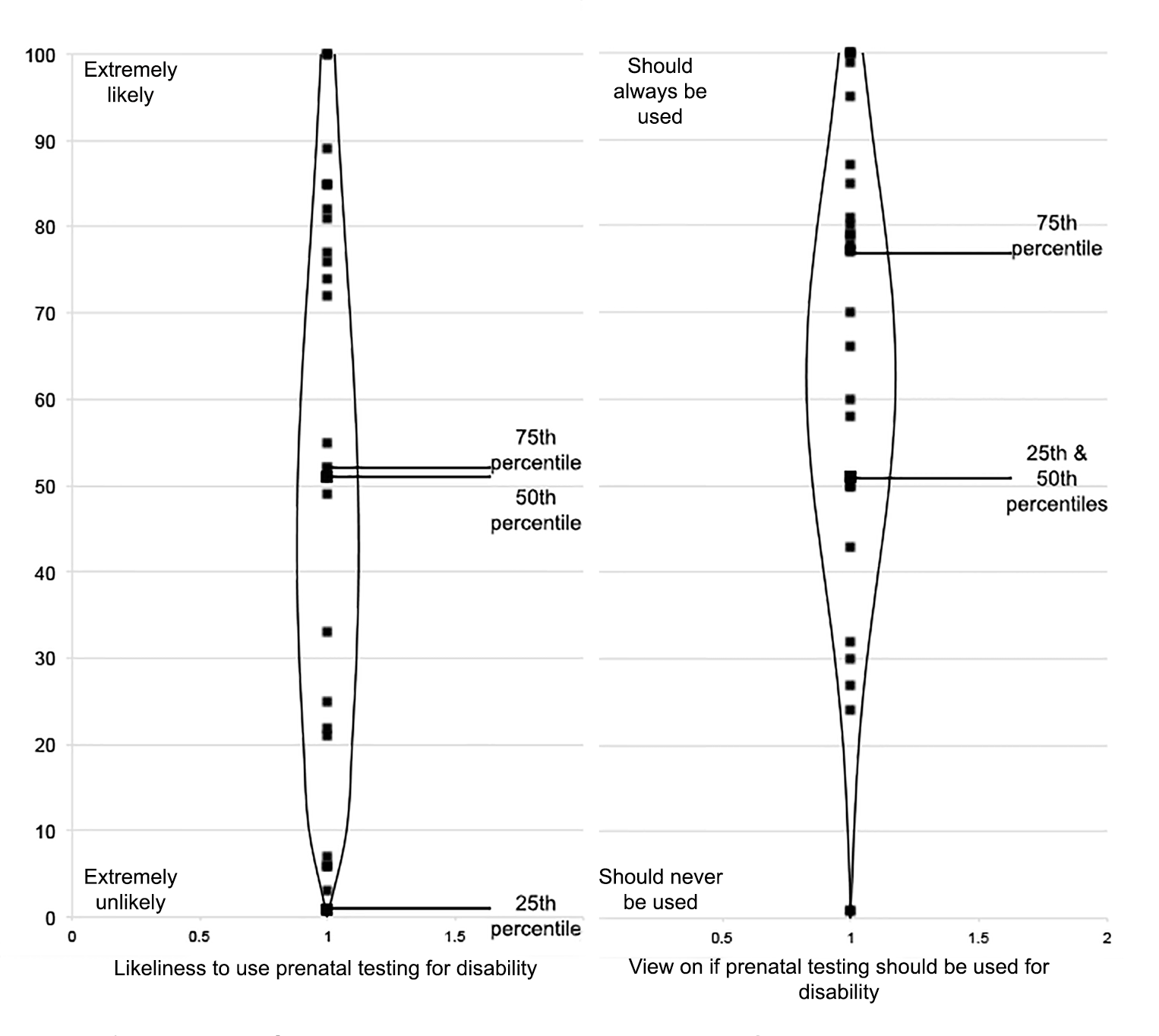

After completing the questions shown in table 4, participants were asked how likely they (or their partner) were to use prenatal testing for disability in the future on a sliding scale from extremely unlikely (1) to extremely likely (100); the mean score was 38.02 (SD = 32.83), which falls in the unlikely range; figure 2 details the distribution of these scores.

Figure 2. Beanplots of prenatal testing questions. The beanplot's shape marks density while the beans indicate distribution.

To determine which variables influence likeliness to use prenatal testing for disability multiple linear regressions were run. In doing so we found that the number of years participants worked in a disability related industry (zero for not applicable) significantly predicted likeliness to use prenatal testing for disability, F(1, 40) = 9.10, p < 0.01, R2 = .19. On average siblings not employed in a disability related industry are expected to score 47.65 (very slightly unlikely to use). Siblings likeliness to use prenatal testing is expected to reduce from 47.65 by 1.02 for every year they work in a disability related industry, the difference is significantly different from zero, t = -3.02, p < 0.01. So for example, a sibling that has worked in a disability industry for 10 years is expected to score 37.45 (not likely to use prenatal testing). One possible reason for this may be that those who work more closely with disabled people may have stronger relationships with disabled people and are therefore less likely to think prenatal testing for disability matters, as is mirrored in our qualitative findings discussed below. However, this result must be interpreted with extreme caution because although likeliness to use prenatal testing was not significantly correlated with age, time employed in a disability industry correlated with participants' age.

Influencing their likeliness to use prenatal testing for disability were siblings' complicated views of and attitudes towards disability. While many articulated the value of disability and understood disability complexities, siblings often also expressed through their responses, whether intentionally or not, that disability was inherently negative. For example, it was not uncommon for participants to connect disability with a lack of heath or abnormality when discussing prenatal testing. For example, one participant commented, 'I love my sister, but I would also wish the best health on my child.' This concept of 'healthy baby' was often invoked as the antithesis to disabled, suggesting many participants believe that disabled people cannot be healthy. This common understanding of disability as in opposition to health links back to medicalized views of disability and as Shakespeare (2012) suggests 'anchors' disability in impairment (Nazil, 2012).

There were other siblings who connected disability to additional difficulties and challenges while explaining their views on prenatal testing. For example, one participant's implicit association with challenges came directly from her sibling experience; she recollected, 'I still struggle with resentment about the childhood that I never had because of the responsibilities I was saddled with as a young child. It's difficult to relive that experience as a parent.' Certainly disabled people can face more challenges than nondisabled people, however not all disabled people face these challenges. Moreover, many of those challenges can be attributed to systemic and environmental factors rather than individuals' impairments (Abberley, 1987; Barnes & Mercer, 2003; Linton, 1998).

Evidencing their complex relationships with disability, siblings often contrasted their love for their disabled sibling with their negative views of disability. For example, when discussing how being a sibling influences their likeliness to use prenatal testing for disability one participant said, 'I did not want to have a disabled child, even though that feeling was a huge betrayal of my sister.' Many other siblings explained their position on prenatal testing for disability, specifically to not have a disabled child, was strongly influenced by their sibling experience. Along the same lines, other siblings supported prenatal testing reasoning it would be beneficial to cure and/or eradicate disability. Because of their negative perceptions of disability it was not uncommon for some participants to believe as one participant suggested, 'I think it [prenatal testing] is a wonderful advancement in medicine because it can help prevent having a child with birth defects.'

While some negative implicit prejudice was apparent through siblings' discussion of disability, there was other evidence that highlighted how the sibling relationship can also cause more intimate and knowledgeable understandings of disability. Although some participants made negative statements about disability, many participants valued their sibling experience and its many benefits. While explaining how being a sibling influenced her views on prenatal testing for disability, one participant detailed,

my parents didn't know my brother had Down syndrome until he was born. They did choose to do the standard test but they were told they had less than a 1% chance of having a baby born with Down syndrome. Oops surprise we were wrong. So yes I think it influences my ideas about prenatal genetic testing. How many parents are having these tests and being told that their baby most likely has this condition or that condition and aborting when realistically those tests are only like 50% accurate if that?

Other participants valued their experience as a sibling because it made them more prepared in terms of their expectations for a potential disabled child. In fact many siblings' answers indicated they understood disability is more than just individual but rather constructed differently depending on contextual and relational factors. For example, one participant commented, "prenatal testing is based on negative preconceptions about disability. While some people may say they would be 'more prepared,' the question is 'for what?'" Likewise, another participant commented, "I think in addition to the testing the couple should get extensive education on disability as a socially constructed concept, to see that disability isn't necessarily a bad thing. I think knowing you are entering that community is helpful to prepare." As such, there were participants who believed thanks to their sibling experience they recognize the value in disability and that disability can be a good thing, which impacted their likeliness to use prenatal testing. For example, one participant said her experience as a sibling "it has a huge impact. I don't see the downside of having a child with a disability." Such diverse responses reveal that within support for prenatal testing, siblings may have a variety of reasons why they support testing. The 2012 passage of the Down Syndrome Information Act, mandating that parents be given accurate and current information on the condition, demonstrates that the move towards more and better information may act as a compromise for those who disagree on both the status and intent of prenatal testing (Leach, 2016).

Broader stakes: Understandings of prenatal testing and other influencing factors

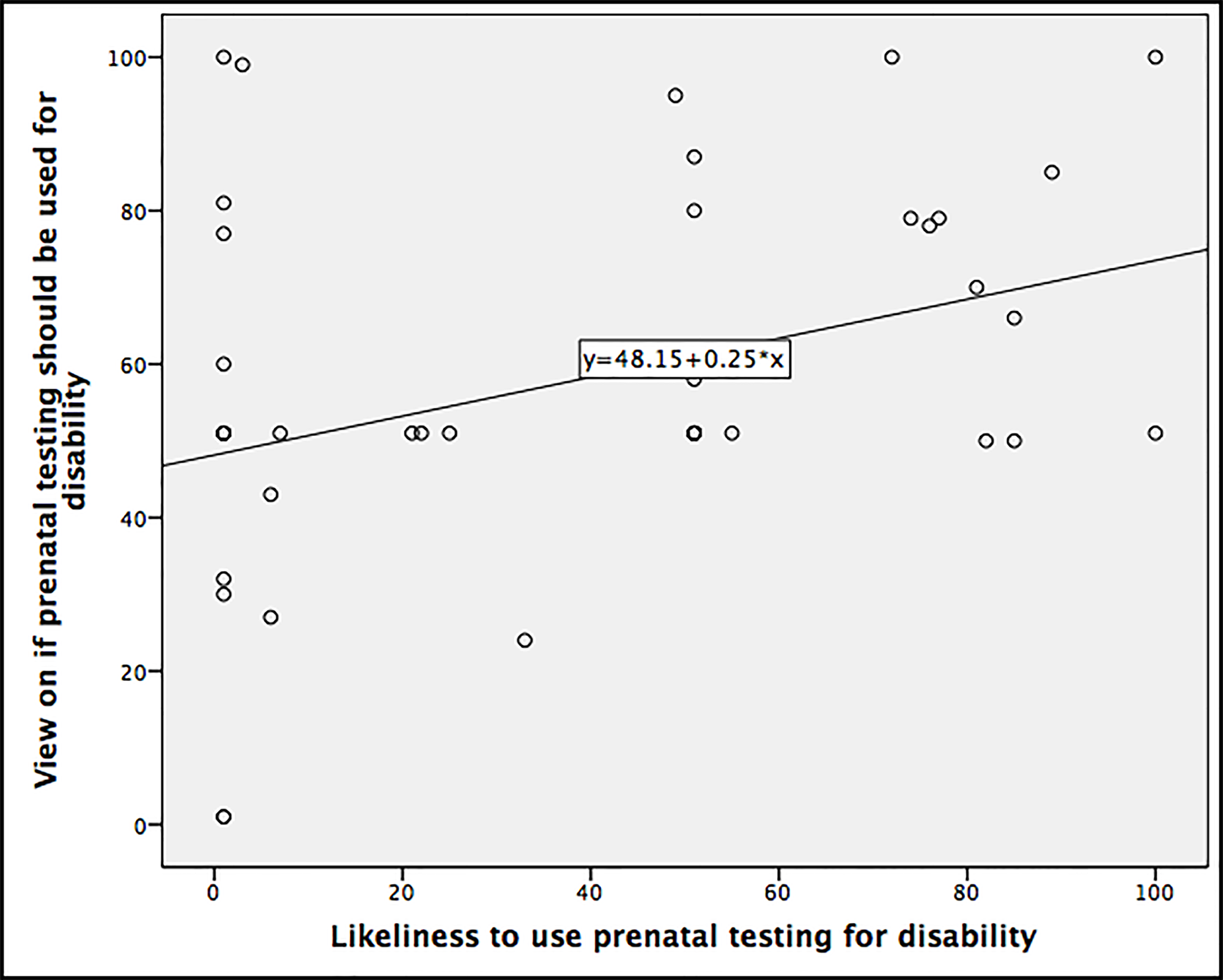

Participants were also asked on a sliding scale what their view of prenatal genetic testing for disability was from should never be used (1) to should always be used (100). The mean score for this question was 57.79 (SD = 22.73), meaning they believed it should be used (see figure 2 for distribution). A linear regression revealed that participants' likeliness to use prenatal testing for disability in the future significantly related to their view on if prenatal testing should be used for disability, F(1,46)=7.13, p =.010 (see figure 3).

Figure 3. Scatter plot of 'likeliness to use prenatal testing for disability' and 'views on if prenatal testing should be used for disability.'

On average, participants in this study were unlikely to use prenatal testing for disability in the future. At the same time participants' mean score revealed they believed prenatal testing should be used for disability. Although we did find a significant relationship between participants likeliness to use prenatal testing for disability and their view on if it should be used for disability, the model was fairly weak (R2 = .13) suggesting there are other complex and possibly confounding variables involved in decisions to use prenatal testing and views on prenatal testing.

Participants' open-ended responses on views of prenatal testing for disability yielded insights about siblings of disabled people's perceptions on prenatal testing itself, including reasons why they might use prenatal genetic testing. Siblings expressed that prenatal genetic testing might be used as a way of preparing oneself for a disabled child through increased knowledge about a condition, in cases of medical need, or because of a family history of genetic disability. In expressing a "preparation" motivation, some respondents connected prenatal testing with love for a possible disabled child: "they would know ahead of time and be prepared and love the baby." Others felt that "being prepared may help you find medical and emotional support within your family, your community or online." Responsibility underlies the narrative of preparation, put simply by one participant: "I felt a responsibility to do all the tests." Responsibility also connects preparation in linking prenatal testing mentioned in conjunction with other components of prenatal care, such as "prenatal doctor care and vitamins for the most healthy baby." Siblings in our sample also connected prenatal genetic testing to preparation, but the anticipation of termination often was the conduit to that that connection. For example, one participant detailed, "if it [prenatal testing] existed then and my mother would have aborted my brother, we all would have missed out on a lot." Just as respondents' understandings of disability are complicated, their attitudes towards the meanings and stakes of prenatal genetic testing itself are ambivalent. One respondent's thoughts capture this well:

it is a very complicated issue for me as I know that some genetic testing ends in terminating the pregnancy. But I am firmly pro-choice and believe that the family should have the choice to test and to take action if they feel like they need it. It's my greatest fear and I also know that I would be fine if it happened.

This expressed ambivalence reflects larger social and bioethical debates over prenatal screening; on one end, the claim that prenatal testing is inherently disparaging of and toward disability (Klein, 2011) and on another end, the claim that prenatal testing reduces suffering and increases personal and familial freedom (Cowan, 2008). Embedded within these debates is the role that knowledge plays in the context of ethical, moral and social decisions. For some siblings in our study, responsibility and preparation came down to gaining a certain kind of knowledge (screening or testing results) weighed against and alongside their own familial and experiential knowledge of life with disability. What is often missed in the debates around prenatal testing, as Rapp and Ginsburg (2001) point out, is that these abstract debate points "come already anchored in the daily and intimate practices of embracing or rejecting kinship with disabled fetuses, newborns, and young children" (p. 534). The infusion of familial and intimate knowledge with disability may provide new insights and new possibilities for thinking through bioethical and social debates around the uses of prenatal testing. It is no longer expedient to resist or deny the prevalence of prenatal testing and other genetic selection technologies; instead, disability studies scholars and activists can and should address the simultaneous delicate and sturdy familial ties that hold promise for such conversations.

Siblings' familial experiences with disabilities do not necessarily predict the relationships between attitudes about prenatal genetic testing and attitudes about disability, but the data, overall, reveals a nuanced understanding of both disability and prenatal genetic testing. We invoke Alison Kafer's (2013) thesis that disability is known and understood in certain ways as a result of a particular relationship to disability (in this case, as a sibling). Siblings of disabled people may hold particular understandings of disability as a cultural phenomenon or group because of their familial experiences with a particular disabled person. This insight, which draws upon Kafer's work, has implications for future research that explores how family members of disabled people may have their own knowledges of disability, and how certain understandings of disability have implications for how siblings of disabled people act.

Some respondents were quick to associate prenatal genetic testing with disabilities or conditions that are not currently testable using prenatal methods. These disabilities included neurodevelopmental or neurological conditions including autism or psychiatric disability. Respondents' connections between genetic testing and neurological conditions reflect the ongoing debates both within the scientific communities and public understandings of science. Though autism and psychiatric disability have not been traditionally part of the conditions that have been diagnosed through prenatal testing, there has been growing interest in the etiologies of these conditions and an increasing willingness to accord heredity as part of such etiologies (Angermeyer et al., 2011; Bumiller, 2009; Melendro-Oliver, 2004; Nadesan 2005). The leap that respondents made in connecting prenatal genetic testing to the rooting out of potentially undesired diagnoses (such as autism) indicates that the tendency to understand particular conditions of the body and mind as genetic is altering public understandings of technoscience (Stempsey, 2006).

Thus in order to further explore these connections, linear regression models were used to determine which variables influence views on usage of prenatal testing for disability. We found a significant relationship between views on prenatal testing for disability and guardianship, F(1,40) = 5.16, p = .03, R2=0.11. In doing so, according to the model non-guardian siblings are expected to slightly favor prenatal testing for disability (54.11 on the sliding scale) while guardian siblings are expected to moderately believe prenatal testing should be used for disability (75 on the sliding scale); the difference is significantly different from 0, t = 2.27, p = 0.03.

Several respondents' open-ended answers could help illuminate the connection between a slightly higher likelihood to use prenatal testing and siblings who either currently act as legal guardians for their disabled siblings or anticipate taking on such a role in the future. For instance, one participant stated,

affordability and care are of great concern as well. Regarding my sister, I am aware that I will one day be held financially responsible and I expect the state will assist my family minimally. I have to take care of my sister before I can even begin to think about taking care of a child.

The comparison between caregiving for a disabled sibling and caregiving for a child is notable and points to an additional motivational factor for the use of prenatal testing. It is also possible that navigating systems and the other legal aspects of guardianship cause extra stress thereby increasing guardian siblings' favorability towards prenatal testing for disability. While theoretically additional closeness may serve to negate some of these stressors, our findings revealed no significant relationship between closeness with a disabled sibling and guardianship suggesting that although guardians may have more procedural duties they may not experience any additional positive benefits from guardianship alone. This finding suggests that there may be something particular about the role expectations of guardianship, and the impacts of guardianship, or alternatives to legal guardianship such as supported decision-making, should continue to be explored in research. While there may be many factors that could contribute to a guardian or caregiver sibling's higher likelihood to use prenatal testing, some siblings in our study seemed to be invoking utilitarian ethics by weighing the potential financial and emotional costs of raising a child with a disability alongside providing support for their disabled sibling. While caregiver burden has been well documented in the literature (Heller & Caldwell, 2006; Murphy et al., 2007), little work has been done to explore how or where the effects of caregiver stress may lead.

Another factor that seemed to color siblings' views on prenatal testing was pregnancy termination. Though our survey did not explicitly ask questions about or invoke termination, the connection of prenatal testing with termination came through in participants' responses. One respondent invoked one possible outcome of preparation as termination by stating, prenatal testing "should be used if people want to have an opportunity to be educated and prepared or if they are unwilling or unable to provide the support needed for a child with serious and chronic health care needs." Several participants rejected termination because of religious pro-life beliefs, such as one participant that stated,

I was raised and still am a devout Catholic. I believe in the sanctity of human life… When I inquired as to why the second test was needed, they said it was to give me time to abort. No second test. Discussion over. I knew that if my child was born with a disability, I would be provided the tools/supports needed to raise him.

Two respondents invoked the statistic of "90+% of women terminated pregnancies when abnormality found" to argue against prenatal genetic testing, or at least register their discomfort with prenatal genetic testing. While this statistic is outdated and has been estimated more recently at 68-72% (Natoli et al., 2012), the mention of this statistic signals an engagement with ongoing debates sparked by disability rights activists and scholars. Concurrently, however, the theme of personal choice was present in the data. One respondent represented a number of individuals by saying, 'it's up to prospective parents to decide whether they want to know the potential future."

Through a linear regression our study also found views on prenatal testing usage for disability (centered), political orientation (centered), and an interaction variable significantly predicted implicit disability prejudice, F(3, 43)=3.63, p=.02, R2=.20. The variable political orientation is significantly different from zero, t = 3.14, p = .003. The expected implicit prejudice values according to this model are detailed in table 5.

| Expected Implicit Prejudice According to the Multiple Regression Model | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Political Orientation (very liberal to very conservative) | Views on Prenatal Testing for Disability (should never be used to should always be used) | ||||

| 1 | 25 | 50 | 75 | 100 | |

| 1 | 0.40 | 0.35 | 0.31 | 0.23 | 0.21 |

| 25 | 0.34 | 0.41 | 0.48 | 0.53 | 0.63 |

| 50 | 0.28 | 0.47 | 0.67 | 0.86 | 1.06 |

| 75 | 0.23 | 0.53 | 0.86 | 1.18 | 1.50 |

| 100 | 0.17 | 0.60 | 1.04 | 1.50 | 1.93 |

| Note. The variables in this model are 'views on prenatal testing for disability' (centered), political orientation (centered), and the interaction variable. | |||||

Implications and Limitations

Our study was the first of its kind to examine the interplay between siblings' unique relationship to attitudes about meanings of disability and views on prenatal testing. In doing so we found siblings have both personal and broader stakes in disability that impact their views on prenatal testing and its usage, and attitudes towards disability. Such findings have implications for theory, future research, and practice. First, though the use of empirical social scientific methods in bioethical inquiry has been debated (Borry et al., 2005; Haimes, 2002), recently the utilization of such methods has become increasingly accepted as critiques of principlism ethics have become increasingly robust (Davies et al., 2015). Indeed, Adam Hedgecoe (2004) has called for a critical bioethics that focuses on the relationship between bioethics and the social sciences. Parsing out how and where "disability" as a set of deeply embedded meanings and relationships is understood, in conjunction with how human actions have implications both for meanings of disability and for disabled people is a task that has the potential to offer insight not only within disability studies but for fields such as critical bioethics. For instance, in our study years worked in a disability industry significantly predicted likeliness to use prenatal testing wherein likeliness to use prenatal testing for disability is expected to reduce for every year siblings have worked in a disability industry. One possible for reason this may be that those who work more closely with disabled people may have stronger relationships with disabled people and are therefore less likely to think prenatal testing for disability matters, as is mirrored in our qualitative findings. Given that social distance (the degree to which an individual is willing to be associated with a stigmatized individual) has been identified as a barrier to full inclusion for disabled people (Ouelette-Kuntz et al., 2010), our finding suggests that context matters. The increased likelihood of siblings choosing disability-related work (Eget, 2009) now takes on greater social and ethical stakes as we consider the relationship to likeliness to use prenatal testing. Here, our work has potential implications for exploring how bioethical issues work "on the ground" for people who would most likely not consider themselves bioethicists. This move very much responds to Hedgecoe's (2004) call for a critical bioethics.

Our findings also offer suggestions for critical disability studies theory. Recent theoretical contributions including Kafer (2013), Meltzer and Kramer (2016), and Mauldin (2012; 2014; 2016) suggest that conceptualizations of disability may be de-individualized by focusing on relationships, and potentially familial relationships, as places where we might learn something about how disability is socially and culturally constructed. Mauldin (2014), for instance, demonstrates how in the context of pediatric cochlear implant therapy, deafness is recast from sensory deficit to neurological issue, placing further responsibilization onto mothers. These mothers, in return, theorize their children's deafness in multiple ways, showing how technology, disability and familial relationships intersect and act upon one another. In our study, the majority of participants had relatively low explicit prejudice in combination with implicit preference for nondisabled people, which mirrors the expressed tension between some siblings' love for their disabled sibling and their negative views of disability. While the sibling relationship leads some participants to experience stress and difficulties and therefore believe prenatal testing should be used to eradicate disability, others connected their sibling experience to the experience and knowledge leading them to understand disability as complex and valuable. Our study follows and extends the theoretical work above by emphasizing how specific relationships (in this case, siblingships) may influence understandings of disability in complex ways. Indeed, the work of accounting for disability and the myriad ways of conceptualizing, experiencing it and acting upon it may necessitate the inclusion of less than "positive" ideas about disability.

In addition, attending to how relationships operate to construct meanings of disability may actually allow scholars and activists to think through the role such relationships play in the formation of new or altered subjectivities. Building on Rapp and Ginsberg's (2001) suggestion that the family is a crucial site for understanding the often side-by-side experiences of inclusion and exclusion, we offer that familial experience with disability, in addition to personal experience with disability, may lead to new ways of being a person. For example, the complex relationship between political orientation, implicit disability prejudice, and views on the use of prenatal testing for disability that appeared in our study cannot and should be explained or rationalized away. The finding that liberal siblings' implicit prejudice goes down as their beliefs about using prenatal testing usage for disability go up, while the opposite is true for conservatives, should spark further research into the roles that contextualized relationships, attitudes, and experiences may play in constructing what many of us come to think of "disability." While more work is needed, this finding could help illuminate what happens when "disability is experienced in and through relationships" (Kafer, 2013, p. 8). Although Furr and Seger (1998) found a relationship between views on prenatal testing and political orientation, the complex association between political orientation, prenatal testing, and views on prenatal testing for disability has never been examined in the literature before our study. While our political orientation sliding scale had the added benefit of avoiding some of the dichotomy of United States political parties (Hershey, 2015; Jacobson, 2012) by allowing participants to place themselves along a continuum, we suggest this complex relationship, including the motivating factors for these differences, be explored further in siblings of disabled people, disabled people, and the general population.

One notable limitation of this study was that participants were volunteers recruited through an organization for siblings of disabled people. Self-selection bias is likely present; there is also a possible uniqueness about these particular siblings since they are connected to this sibling organization in some way. Moreover, the majority of our participants were White women and this limitation must be considered when interpreting our findings, as it is not an accurate representation of the general population. Past research has also found women to have more favorable attitudes towards disability than men (Hirschberger, Florian, & Mikulincer, 2005).

Despite its prominence and strengths in terms of validity (Aaberg, 2012; Pruett, 2004; Pruett & Chan, 2006; White, Jackson, & Gordon, 2006) and reliability (Pruett, 2004; Pruett & Chan, 2006; Thomas, Vaughn, Doyle, & Bubb, 2013), our implicit measure (the DA-IAT) may not be able to fully capture the complexities of implicit disability attitudes, both because it presents disability versus non-disability in such a strict oppositional fashion, and because it tends to focus on physical disability despite aiming to be across-disability (Friedman, 2016). We invite future researchers to consider these limitations as opportunities to develop new methods to measure implicit attitudes about disability. However, the findings themselves are very much in accordance with current disability studies theory and even extend possibilities for future research on siblings' implicit and explicit attitudes on disability that might utilize other methodologies.

By interweaving quantitative data on siblings' conscious and unconscious disability attitudes and prenatal testing with their qualitative explanations of their views of prenatal testing, we were able to explore siblings' unique relationships with disability. The phenomenon of prenatal genetic testing was used as a way to elicit understandings about the technology itself and social meanings of disability. As prenatal testing technologies advance and are increasingly used, it is important to understand the bidirectional relationships between prenatal testing and understandings of disability, particularly how certain groups, including siblings of disabled people, may view prenatal testing usage, and how prenatal testing may reinforce negative individualized views of disabled people.

References

- Aaberg, V. A. (2012). A path to greater inclusivity through understanding implicit attitudes toward disability. The Journal of nursing education, 51(9), 505-510. http://dx.doi.org/10.3928/01484834-20120706-02

- Akolekar, R., Beta, J., Picciarelli, G., Ogilvie, C., & D'Antonio, F. (2015). Procedure-related risk of miscarriage following amniocentesis and chorionic villus sampling: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol, 45(1), 16-26. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/uog.14636

- Amodio, D. M., & Mendoza, S. A. (2011). Implicit intergroup bias: cognitive, affective, and motivational underpinnings. In B. Gawronski & B. K. Payne (Eds.), Handbook of implicit social cognition: Measurement, theory, and applications (pp. 353-374). New York City: Guilford Press.

- Angermeyer, M. C., Holzinger, A., Carta, M. G., & Schomerus, G. (2011). Biogenetic explanations and public acceptance of mental illness: systematic review of population studies. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 199(5), 367-372. http://dx.doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.110.085563

- Antonak, R. F., & Livneh, H. (2000). Measurement of attitudes towards persons with disabilities. Disability and Rehabilitation, 22(5), 211-224. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/096382800296782

- Appelbaum, L. D. (2001). The Influence of Perceived Deservingness on Policy Decisions regarding Aid to the Poor. Political Psychology, 22(3), 419-442. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/0162-895X.00248

- Archambault, M. E., Van Rhee, J. A., Marion, G. S., & Crandall, S. J. (2008). Utilizing Implicit Association Testing to Promote Awareness of Biases Regarding Age and Disability. Journal of Physician Assistant Education, 19(4). http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01367895-200819040-00003

- Arnold, C. K., Heller, T., & Kramer, J. (2012). Support Needs of Siblings of People with Developmental Disabilities. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 50(5), 373-382. http://dx.doi.org/10.1352/1934-9556-50.5.373

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative research in psychology, 3(2), 77-101. http://dx.doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Bryant, L., Hewison, J. D., & Green, J. M. (2005). Attitudes towards prenatal diagnosis and termination in women who have a sibling with Down's syndrome. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 23(2), 181-198. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02646830500129214

- Borry, P., Schotsmans, P., & Dierickx, K. (2005). The birth of the empirical turn in bioethics. Bioethics, 19(1), 49-71. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8519.2005.00424.x

- Bumiller, K. (2009). The Geneticization of Autism: From New Reproductive Technologies to the Conception of Genetic Normalcy. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 34(4), 875-899. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/597130

- Burke, M. M., Arnold, C. K., & Owen, A. L. (2015). Sibling Advocacy: Perspectives About Advocacy From Siblings of Individuals With Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. Inclusion, 3(3), 162-175. http://dx.doi.org/10.1352/2326-6988-3.3.162

- Burke, M. M., Taylor, J. L., Urbano, R., & Hodapp, R. M. (2012). Predictors of Future Caregiving by Adult Siblings of Individuals With Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. American journal on intellectual and developmental disabilities, 117(1), 33-47. http://dx.doi.org/10.1352/1944-7558-117.1.33

- Cowan, R. (2008). Heredity and hope: The case for genetic screening. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. http://dx.doi.org/10.4159/9780674029927

- Davies, R., Ives, J., & Dunn, M. (2015). A systematic review of empirical bioethics methodologies. BMC medical ethics, 16(1), 1. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12910-015-0010-3

- Dovidio, J. F., & Gaertner, S. L. (2004). Aversive racism. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 36(1), 1-52. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(04)36001-6

- Dovidio, J. F., Gaertner, S. L., Anastasio, P. A., & Sanitioso, R. K. (1992). Cognitive and motivational bases of bias: Implications of aversive racism for attitudes toward Hispanics. In S. B. Knouse, P. Rosenfeld & A. Culbertson (Eds.), Hispanics in the workplace (pp. 75-106). Newbury Park, California: Sage Publications. http://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781483325996.n5

- Eget, L. A. (2009). Siblings of those with developmental disabilities: career exploration and likelihood of choosing a helping profession (Doctoral dissertation). Indiana, PA: Indiana University of Pennsylvania.

- Federici, S., & Meloni, F. (2009). Making decisions and judgments on disability: the disability representation of parents, teachers, and special needs educators. JEIC, 1, 20-26.

- Friedman, C. (2016). Aversive ableism: Subtle prejudice and discrimination towards disabled people (Doctoral dissertation). University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/10027/20940

- Friedman, C. (in press). Siblings of people with disabilities' explicit and implicit disability attitude divergence. Journal of Social Work in Disability & Rehabilitation.

- Friedman, C. & Awsumb, J. (in preparation). The symbolic ableism scale.

- Furr, L. A., & Seger, R. E. (1998). Psychosocial predictors of interest in prenatal genetic screening. Psychological Reports, 82(1), 235-244. http://dx.doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1998.82.1.235

- Gallagher, J. (1987). Prenatal invasions & interventions: What's wrong with fetal rights. Harv. Women's LJ, 10, 9.

- Garthwaite, K. (2011). 'The language of shirkers and scroungers?' Talking about illness, disability and coalition welfare reform. Disability & Society, 26(3), 369-372. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2011.560420

- Gonter, C. (2004). The expressivist argument, prenatal diagnosis, and selective abortion: an appeal to the social construction of disability. Macalester Journal of Philosophy, 13(1), 3.

- Greenwald, A. G., McGhee, D. E., & Schwartz, J. L. K. (1998). Measuring individual differences in implicit cognition: The implicit association test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(6), 1464-1480. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.74.6.1464

- Greenwald, A. G., Nosek, B. A., & Banaji, M. R. (2003). Understanding and using the implicit association test: I. an improved scoring algorithm. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(12), 197-216. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.197

- Haimes, E. (2002). What can the social sciences contribute to the study of ethics? Theoretical, empirical and substantive considerations. Bioethics, 16(2), 89-113. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1467-8519.00273

- Hall, A. C., & Kramer, J. (2009). Social Capital Through Workplace Connections: Opportunities for Workers With Intellectual Disabilities. Journal of Social Work in Disability & Rehabilitation, 8(3-4), 146-170. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15367100903200452

- Harris, L. T., & Fiske, S. T. (2007). Social groups that elicit disgust are differentially processed in mPFC. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 2(1), 45-51. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsl037

- Hedgecoe, A. M. (2004). Critical bioethics: Beyond the social science critique of applied ethics. Bioethics, 18(2), 120-143. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8519.2004.00385.x

- Heller, T., & Caldwell, J. (2006). Supporting aging caregivers and adults with developmental disabilities in future planning. Mental Retardation, 44(3), 189-202. http://dx.doi.org/10.1352/0047-6765(2006)44[189:SACAAW]2.0.CO;2

- Heller, T., & Kramer, J. (2009). Involvement of Adult Siblings of Persons With Developmental Disabilities in Future Planning. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 47(3), 208-219. http://dx.doi.org/10.1352/1934-9556-47.3.208

- Henry, P. J., & Sears, D. O. (2002). The Symbolic Racism 2000 Scale. Political Psychology, 23(2), 253-283. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/0162-895X.00281

- Hershey, M. R. (2015). Party politics in America (16 ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education, Inc.

- Hirschberger, G., Florian, V., & Mikulincer, M. (2005). Fear and compassion: A terror management analysis of emotional reactions to physical disability. Rehabilitation Psychology, 50(3), 246-257. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0090-5550.50.3.246

- Hodapp, R. M., Glidden, L. M., & Kaiser, A. P. (2005). Siblings of persons with disabilities: Toward a research agenda. Mental retardation,43(5), 334-338.

- Imrie, R. F., & Wells, P. (1993). Disablism, planning, and the built environment. Environment and Planning C, 11, 213-213. http://dx.doi.org/10.1068/c110213

- Jacobson, G. C. (2012). The electoral origins of polarized politics evidence from the 2010 cooperative congressional election study. American Behavioral Scientist, 56(12), 1612-1630. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0002764212463352

- Kafer, A. (2013). Feminist, queer, crip. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

- Klein, D. A. (2011). Medical disparagement of the disability experience: empirical evidence for the "expressivist objection". AJOB Primary Research, 2(2), 8-20. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/21507716.2011.594484

- Leach, M. (2016). The Down syndrome information act: Balancing the advances of prenatal testing through public policy. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 54(2), 84-93. http://dx.doi.org/10.1352/1934-9556-54.2.84

- Manhire, K. M., Hagan, A. E., & Floyd, S. A. (2007). A descriptive account of New Zealand mothers' responses to open-ended questions on their breast feeding experiences. Midwifery, 23(4), 372-381. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2006.01.002

- Melendro-Oliver, S. (2004). Shifting concepts of genetic disease. Science Studies, 17(1), 20-33.

- Meltzer, A., & Kramer, J. (2016). Siblinghood through disability studies perspectives: diversifying discourse and knowledge about siblings with and without disabilities. Disability & Society, 31(1), 17-32. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2015.1127212

- Merriam, S. B. (2009). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Murphy, N. A., Christian, B., Caplin, D. A., & Young, P. C. (2007). The health of caregivers for children with disabilities: caregiver perspectives. Child: care, health and development, 33(2), 180-187. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2214.2006.00644.x

- Nadesan, M. H. (2003, October). Constructing autism. Presentation at Autism and Representation: Writing, Cognition, Disability, Cleveland, OH.

- Natoli, J. L., Ackerman, D. L., McDermott, S., & Edwards, J. G. (2012). Prenatal diagnosis of Down syndrome: a systematic review of termination rates (1995–2011). Prenatal diagnosis, 32(2), 142-153. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/pd.2910

- Nazli, A. (2012). "I'm Healthy": Construction of health in disability. Disability and health journal,5(4), 233-240. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2012.06.001

- Nosek, B. A., Smyth, F. L., Hansen, J. J., Devos, T., Lindner, N. M., Ranganath, K. A., … Banaji, M. R. (2007). Pervasiveness and correlates of implicit attitudes and stereotypes. European Review of Social Psychology, 1(1), 1-53. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10463280701489053

- Ostrove, J. M., & Crawford, D. (2006). "One lady was so busy staring at me she walked into a wall": Interability relations from the perspective of women with disabilities. Disability Studies Quarterly, 26(3). http://dx.doi.org/10.18061/dsq.v26i3.717

- OToole, C. (2013). Disclosing our relationships to disabilities: An invitation for disability studies scholars. Disability Studies Quarterly, 33(2). http://dx.doi.org/10.18061/dsq.v33i2.3708

- Ouellette-Kuntz, H., Burge, P., Brown, H. K., & Arsenault, E. (2010). Public attitudes towards individuals with intellectual disabilities as measured by the concept of social distance. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 23(2), 132-142. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3148.2009.00514.x

- Parens, E., & Asch, A. (2000). Prenatal testing and disability rights. Georgetown University Press.

- Post, L. F. (1996). Bioethical consideration of maternal-fetal issues. Fordham Urb. LJ, 24, 757.

- Proctor, S. N. (2011). Implicit bias, attributions, and emotions in decisions about parents with intellectual disabilities by child protection workers. (Doctor of Philosophy), Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA.

- Pruett, S. R. (2004). A Psychometric Validation of a Disability Attitude Implicit Association Test (Doctoral dissertation). University of Wisconsin Madison, Madison, WI.

- Pruett, S. R., & Chan, F. (2006). The development and psychometric validation of the Disability Attitude Implicit Association Test. Rehabilitation Psychology, 51(3), 202-213. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0090-5550.51.3.202

- Rapp, R., & Ginsburg, F. D. (2001). Enabling disability: Rewriting kinship, reimagining citizenship. Public Culture, 13(3), 533-556. http://dx.doi.org/10.1215/08992363-13-3-533

- Rothschild, J. (2005). The dream of the perfect child. Indiana University Press.

- Sears, D. O., & Henry, P. J. (2003). The origins of symbolic racism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(2), 259-275. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.259

- Shakespeare, T. (2012). Still a health issue.Disability and health journal, 5(3), 129-131. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2012.04.002

- Solinger, R. (1998). Abortion wars: A half century of struggle, 1950-2000. Univ of California Press.

- Stempsey, W. E. (2006). The geneticization of diagnostics. Medicine, health care and philosophy,9(2), 193-200. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11019-005-5292-7

- Stewart, J., Harris, J., & Sapey, B. (1999). Disability and dependency: origins and futures of 'special needs' housing for disabled people. Disability & Society, 14(1), 5-20. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09687599926343

- Thomas, A., Vaughn, E. D., Doyle, A., & Bubb, R. (2013). Implicit Association Tests of Attitudes Toward Persons With Disabilities. The Journal of Experimental Education, 82(2), 184-204. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00220973.2013.813357

- Wertz, D. C., Rosenfield, J. M., Janes, S. R., & Erbe, R. W. (1991). Attitudes toward abortion among parents of children with cystic fibrosis. American journal of public health, 81(8), 992-996. http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.81.8.992

- White, M. J., Jackson, V., & Gordon, P. (2006). Implicit and explicit attitudes toward athletes with disabilities. Journal of Rehabilitation, 72(3).

Endnotes

-

In the literature, it is common for the term 'siblings of disabled people' to be used to denote the absence of disability. Sometimes the phrase 'typical siblings' is used as well. Though we have retained the term "siblings of disabled people," we do not claim that this label illustrates a binary. Indeed, 14% (n=7) of our sample self-identified as having a disability.

Return to Text -

It should be noted one participant did not complete the DA-IAT therefore their score was excluded.

Return to Text